By Rachel Druck

Simchat Torah is a holiday that celebrates the Torah and the Jewish people’s continuous connection to it. In honor of the holiday, below is the story of over 1,000 Torah scrolls that were saved from destruction.

Walking through the new Synagogue Hall at Beit Hatfutsot, it is clear that while Jews throughout the world may have different customs and practices, the world of the synagogue can be a uniting force in Jewish life. However, there is one thing in particular that unites nearly 1,400 synagogues around the world: they are home to a Czech Torah Scroll.

The story of how thousands of Torah scrolls made their way from the former Republic of Czechoslovakia to locations as far-flung as New Zealand, the United States, and South America, begins during World War II, when a group of curators and intellectuals worked against the clock to save religious objects from congregations throughout Bohemia and Moravia.

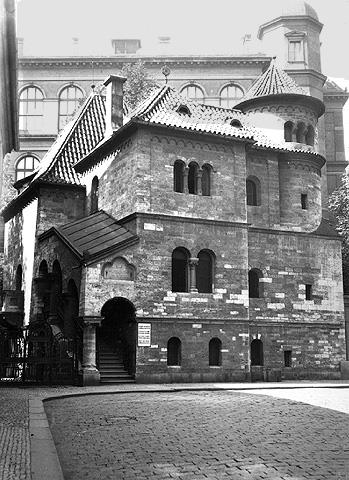

The Jewish Museum in Prague was originally established in August 1906, and exhibited Jewish objects from Prague and the region of Bohemia. Many of the objects it exhibited were, presciently, from synagogues that were destroyed when the Prague ghetto was torn down. By the time that the Nazis occupied the former Republic of Czechoslovakia and established the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in March of 1939, the Jewish Museum in Prague included nearly 800 items.

In September of 1941 Jews were forbidden from holding services in synagogues, the latest in a series of discriminatory laws enacted against the Protectorate’s Jews. Shortly thereafter, in December, the museum was converted into a storehouse for the objects removed from the synagogues in Prague. As Jews throughout the region began to be deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto, and from there to concentration and death camps, the Prague Jewish Community (the organization that ran the city’s Jewish community and later became the authoritative body of the region’s Jews) recognized the importance of preserving as much as possible from the disappearing communities of Bohemia and Moravia. They began merging and centralizing the collections of a number of Jewish museums, creating the Central Jewish Museum of Prague.

Though the museum and the Prague Jewish Community were controlled by the Nazi’s Central Office for Jewish Emigration (later the Central Office for the Regulation of the Jewish Question in Bohemia and Moravia), most of the planning and organizing for collecting materials was carried out by the Prague Jewish Community, particularly the founder and curator of the Jewish Museum in Prague, Salomon Hugo Lieben, and the Jewish Museum in Mikulov, Alfred Engel. A popular explanation for why the museum was permitted to carry out its work is that the Nazis were preparing to create a “Museum of an Extinct Race.” However, there is actually no credible evidence suggesting this to be the case. In fact, it was likely a combination of factors—including wanting to know which confiscated items could be valuable, and the general Nazi tendency towards wanting to organize and catalogue confiscated property—and not any postwar plans that incentivized the Nazis of the Central Office to approve the plans put forth by the Prague Jewish Community.

On August 3, 1942 the call went out from the Central Jewish Museum in Prague to Jewish communities throughout the Protectorate, with instructions to send every single item from their synagogues, including ritual objects, books, and archives, to the museum. Those who worked at the museum knew that they were responsible for saving and preserving the remnants of Jewish life throughout Bohemia and Moravia, and did what they could to collect and document as many items as possible. At the same time, they had to be extraordinarily careful when working with the Nazi authorities so that they would be allowed to continue their work. Through this delicate and extensive efforts, workers at the Central Jewish Museum in Prague undermined the Nazi confiscation of Jewish property, transforming the extensive Nazi looting into a rescue of Jewish history and life.

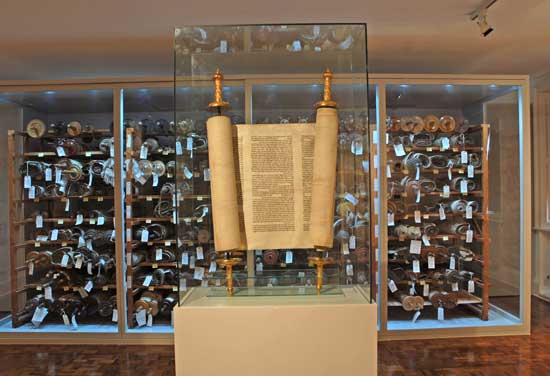

However, though they managed to save the remnants of Jewish life throughout Bohemia and Moravia, those working at the museum ultimately could not save themselves. In the end all of those who worked at the Central Museum were deported, and only two of the core group of curators survived, Hana Volavkova and Karel Stein (both would return to work in the museum after the war). What they managed to do, however, was incredible. By the time that the museum ceased to function in February 1945, a result of the deportations that left no one to run it, items from 136 former communities throughout the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia had been collected. This included 212,822 ritual objects, books, and archives, among which were 1,564 Torah scrolls. Ultimately, their work was so organized and detailed that their card catalogue can be used to this day to accurately identify the objects they collected.

Czech Torah Scrolls

For the Torah scrolls that had been sent from congregations throughout Bohemia and Moravia to the Central Jewish Museum, their journey was only beginning. After World War II these scrolls remained in the Central Museum, which had been renamed the State Jewish Museum in Prague, neglected and in danger of decay. While the museum workers may have hoped during the war that the objects they collected would eventually be returned to their original communities, in the end there was generally no one left to give them to and they were left to languish. In 1963 government officials approached the art dealer Eric Estorick, hoping that he might be able to help them find an individual or organization who would be willing to provide a new home for these orphaned Torah scrolls. Estorick eventually contacted one of his clients, Ralph C. Yablon, who in turn contacted his rabbi, Harold F. Reinhart of London’s Westminster Synagogue. Coincidentally, Rabbi Reinhart had been thinking of establishing a Holocaust memorial exhibition in the synagogue, and agreed that it would be a good idea to have some of the scrolls moved to the synagogue as part of the memorial. Yablon then proceeded to purchase all 1,564 scrolls, and had them sent to the Westminster Synagogue.

Happily, Rabbi Reinhart was willing to deal with the unexpected influx of Torah scrolls, which began arriving on February 5, 1964. A Memorial Scrolls Committee was organized, and began registering the Torahs and categorizing them according to their condition and whether they were fit for reuse. Those that were categorized as “Unusable” were designated for display, while the rest were repaired by the scribe David Brand for use in synagogues. Since the ‘60s, nearly 1,400 scrolls have been sent on permanent loan to congregations around the world, with the majority located in the United States.

While the workers at the Central Jewish Museum in Prague could not ultimately save the Jewish communities of Bohemia and Moravia, their efforts to rescue what they could from these communities ultimately strengthened and united postwar Jewish communities, and allowed the communities of Bohemia and Moravia to live on through them. The work of the Central Jewish Museum in Prague during World War II was both a form of quiet resistance to the Nazi regime, as well as an ultimate demonstration of the endurance and interconnectedness of Jewish communal life.

Rachel Druck is the editor of the Communities Database at Beit Hatfutsot – The Museum of the Jewish People.