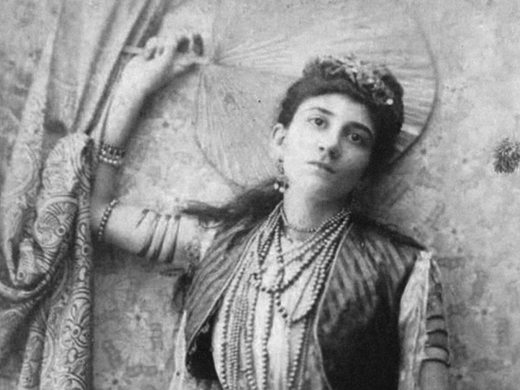

Take some kids with the worst learning problems you can imagine, and try to tell them about the Dreyfus affair: they are most likely to take some interest in the story of the French Jewish officer who in 1895 was convicted treason, exiled to the Devil’s Island, then thanks to a passionate campaign by supporters and intellectuals such as Émile Zola, with wide public support, was given a second trial and received a pardon from the president of France. Now try to tell the same kids about Rachel Sassoon Beer, the journalist who had came up with the exclusive story that brought to Dreyfus’ acquittal and pardon after – and you lost them completely. And not only them – most of us did not even come across her name, she is not mentioned in Israeli history books – now we attempt to right this wrong. Let us start from Rachel’s fascinating family background.

Four decades after Mayer Amschel from Frankfurt scattered his five sons around the world and established the Rothschild Empire, David Sassoon from Bombay pulled the same strategy with is eight sons, some of which settled in Britain. The Sassoons had business worldwide, including Shanghai, Hong Kong, Bombay, and England. They traded in cotton, coffee and opium, owned banks, real estate networks and more. They were called the Rothschild of the East for their enormous wealth.

Sassoon David Sassoon arrived at Britain, and soon became an enthusiastic Anglophile, well integrated in the high society of Victorian England, while strictly observing all Jewish practices, thus fulfilling his father’s wish, who made his sons promise him that wherever they are they shall not stray from the Jewish heritage and tradition. He made sure they kept their promise by writing in his will that should his descendants marry a non-Jew, they shall be disinherited.

Rachel was Sassoon David Sassoon’s daughter. Brought up as a privileged lady, she was educated in private schools and lived in the family mansion in London, surrounded by governesses and servants. When she reached adulthood her parents wished to marry her to a wealthy man from the Jewish community, however she was a rebel and would not spend her life in forced utility marriage just to please the grandfather she never knew. She married Frederick Beer, a non-Jewish financier, and converted to Christianity. Her family, needless to say, had no mercy, and according the will – Rachel was cut off at once from the family’s fortune, as well as from any family ties.

Obviously she did not suffer from poverty. Her husband was from a family of banking magnates, who owned, among other assets, “The Observer” – the oldest weekly in England (since 1794). Rachel fell in love with the world of journalism at first sight. Soon she was publishing her own articles in the newspaper, conveying her socialist world view; her support in workers’ unions; and the resentment she held against the hypocrisy and self-righteousness of the British high society, as well as its diminishing attitude towards women.

Eilat Negev and Yehuda Koren wrote a wonderful biography called “The first lady of Fleet Street”, unfolding the story of Rachel Beer. They mention her views regarding women’s rights in her time:

“Few among women can be lover, mother, gourmet, saint, brilliant conversationalist, a good house keeper, mistress, companion, and nurse all at the same time. Men expect too much.”

This may not sound much to 21th century feminists, but back then – when Edwardian mothers used to guide young brides to “lie back and think of England” at their wedding night – it was a courageous statement.

Realizing that her gender would hold her back, she chose a sophisticated way to break the glass ceiling. In 1893 she persuaded her husband to buy the “Sunday Times”, the Observer’s competing newspaper, and to appoint her – a woman of Jewish origin whose family came from Bombay – chief editor of both newspapers, thus becoming the most influencing Sunday editor in Britain, while women did not even have the right to vote for parliament.

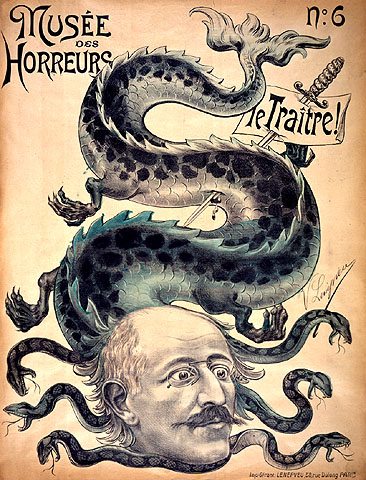

Though some tried to argue that she only got the position for her husband’s status and fortune, she proved to be a brilliant editor, with immense talent, excellent journalistic senses and a moral conscience, that led her to publish one of the greatest exclusives in the history of “The Observer” – Ferdinand Esterhazy’ revealing that the documents for which Dreyfus was convicted were forged. In their book, Koren and Negev describe in fascinating details how Rachel met Esterhazy in a hotel in London where he was staying; how he told her about the forgery; how much money he demanded for the exclusive; his regrets; and finally her decision to actually publish the sensational story.

Though officially a converted Christian, Rachel was always emphatic and caring towards her fellow Jews, and stood up daringly against the anti-Semitic atmosphere during the Dreyfus’ trial. Rachel refused to let the affair off the press agenda* and kept covering the story using all her influence, maintaining the trial as an international affair. Culture and journalism researchers agree that in the anti-Jewish turbulent of the time, the editorials of “The Observer” and the “Sunday Times”, siding with Dreyfus, were the finest hour of these media establishments.

After the death of her husband, who was her soul mate and closest friend, in 1903, Rachel lost her energies and enthusiasm. They had no children and she had no contacts with her relatives, therefore she became more and more depressed and lost all interest in politics and social issues. Her passion to journalism died with Frederick, and soon after his death she sold both newspapers.

Rachel Sassoon Beer died in 1927 and was almost completely forgotten. On her tombstone, only the following words are carved: “the daughter of David Sassoon”.