After the Nazis came to power in Germany 1933, some half a million German Jews were gradually leaving Germany. The vast majority of those descendants of Ashkenazi communities, who lived along the Rhine since the ninth century fled to America and Great Britain, while a small 10% chose to immigrate eastwards to the Land of Israel. They were welcomed not only by mosquitoes and swamps, but also with humiliating and condescending attitude from the veteran Israelis. Much like Jews from Arab lands, who were given offensive nicknames, German immigrants too suffered mocking insults. They were called “The Yekkes”, one interpretations of which being a Hebrew acronym for “fails to understand”, or simply – stupid. A bit strange, given that during the 1930’s, seven Nobel Prize laureates were German Jews.

Cultural and mental barriers were soon set up between the German immigrants and the Yishuv in Israel. The “Yekkes” were well educated, highly professional, and had high standards of precision and perfection, inherent awareness to aesthetics, and a tendency to choose liberal professions – all of which was despised by the socialists land workers who formed the ideal prototype of the Zionist movement.

Coming from the cradle of Western culture, from the home Goethe and Schiller, Marx and Nietzsche, into a desolate, undeveloped Levantine place, was for many of the “Yekkes” a great fall. They would not fit in, and were the ultimate outsiders in the chaotic and careless Zionist culture. And the worst, unforgivable thing – they spoke German, the language of Hitler! The new comers, who wished to preserve their language – in which great works such as Faust, Graetz’s The History of the Jews, and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity were written – were required to eliminate all track of German and German accent from their speech. German-language newspapers were closed, shop windows with signs in German were smashed, and Moshavim of German immigrants were frequently visited by the hooligans of the “Central Council for the Preservation of the Hebrew Language”, an official organization headed by Menachem Ussishkin, who terrorized anyone who would not use any other language but Hebrew.

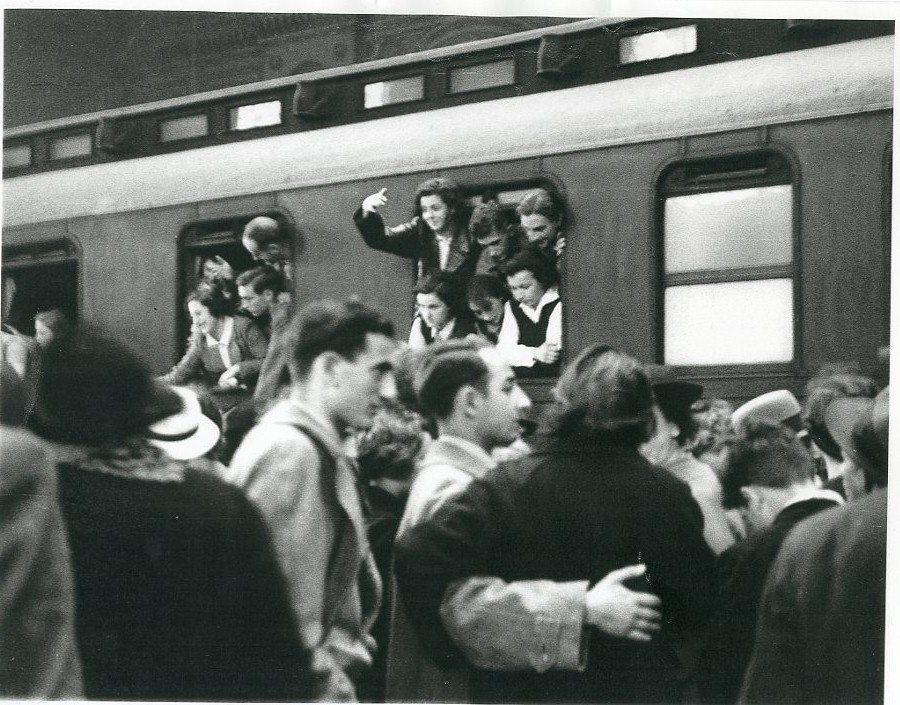

In his book “The Seventh Million”, historian Tom Segev describes the sad, tragic story of the German Jews in Israel, or “the immigrants”, as the admired leader Ben-Gurion called them in disrespect. While the second and third Aliyot were considered ideological “pioneers”, the Germans were looked upon as refugees. Ben-Gurion demanded that they go through a “mental revolution”; Berl Katznelson, the spiritual labor leader, claimed that the Jews of Germany were “not real Jews”; author Moshe Ya’akov Ben Gavriel advised them to “assimilate humbly”; and in the newspapers of the Yishuv their strict, square characteristics were ridiculed time after time. One word-to-mouth story told of a German Jew who traveled by train to Nahariya, and sat backwards the whole way, which caused him vertigo and headaches. When asked why he didn’t ask the person across from him to switch places, he said: “that’s was the problem. I couldn’t ask, because no one was sitting there.”

The irony in this sociological role reversal is fascinating. Whereas in their homeland, Germany, the Jews looked down on the masses of “Ostjuden” who filled the country during the 1920’s – in the Land of Israel the latter looked down on them. This hierarchy reversal resulted in great frustration. Ben-Gurion analyzed the inner world of the German Jews, and explained: “they have both a superiority and inferiority complex. On the one hand they say, we are disciples of the German culture, we had Kant and Beethoven, we read the best literature and studied the German philosophers – and here – well, this is merely Eastern Europe. On the other hand, these “Ostjuden” came here first and managed to do a great deed here. They came early and took over everything.”

The alienation and disrespect towards the Germans were greatly unjust, as there are so many evidences of their enormous contribution to the development of the state, especially in cities like Haifa and Tel Aviv. Tom Segev wrote: The Olim from Germany, together with others, changed the profile of the cities by planning new houses in a practical Bauhaus style, which was the cutting edge in architecture; they opened shops and modern department stores that were not seen until then, some had two large showcases on each side; they introduced a whole new variety of products, such as office supplies, housewares, leather products, cosmetics, children shoes, candies, tobacco. Tel Aviv, until then a small provincial town, was becoming a city of the world, and all of a sudden you could see European Cafés everywhere.” One of the first Cafés were Rivoli Café, where a few excited gymnasia students shattered the windows because they heard the owner speak to his clients in German.

Over time, German immigrants learned to walk proudly upright, and the Yishuv on the other hand learned to appreciate their achievements. New waves of mass immigration flooded the new country, and the Israeli melting pot would not rest.

Many years later, in 1979, a German-born Israeli appealed to the supreme court against the screening of a documentary film called “Yekkes”, claiming that the word “Yekkes” was a a derogatory name. One of the three supreme court judges was the late Haim Cohen – a proud Yekke himself. By that time, the immigrants from Germany and their descendants had already settled in the top of Israeli society, and the word “Yekkes” ceased to be a curse, and filled Cohen with nostalgic sentiments. He simply did not agree the Yekkes had anything to complain about, so he rejected the appeal.