“If journalism aims to serve the public, it must strive for as large circulation as possible. And the reason is simple – larger circulation means more publicity, which means more money, which means optimal journalistic freedom” – said Joseph Pulitzer, the Jewish journalism magnate who immigrated to America in the 19th century and was one of the founding fathers of American journalism, along with William Hearst.

Though Pulitzer prospered in Uncle Sam’s country, he obtained the basic principles in his land of origin, Hungary. His quote defines the four elements of the financial model of journalism ever: journalism=publicity=money=freedom. These four bases also reflect the story of the Jewish Journalism empire that flourished in Hungary in the late 19th century and was part of the cultural revolution in Hungarian Jewry.

In 1867, after centuries of discrimination and oppression, the Jews of Hungary were emancipated. After the emancipation, they stormed the free market so vigorously, that historians believe the Jews’ great impact on Hungarian economy during the 19th century was unmatched anywhere else.

Ironically, it was their centuries long exclusion from traditional guilds and the ban on possessing property, that helped the Jews develop skills they could use after the industrial revolution. In other words, the cruel natural selection caused by the industrial revolution, introducing new professions and replacing the old feudal system, made the Jews more fit and prepared for the new system. Their experience and expertise in various fields of commerce, their education to literacy and their ambitious nature, typical to minorities, gave them advantage over the local population, that was primarily consisted of peasants.

In early 20th century there were approximately 900,000 Jews living in Hungary, 80% of them were free professionals working in various industries, whereas 70% of the general population were farmers or farmhands.

Hungarian Jews were considered pioneers in many diverse industries: The Goldenberg family founded the textile industry; Mandel Brant introduced steam machinery, and Jewish entrepreneurs established the first insurance company in Hungary. But undoubtedly, the icing on the cake was their influence on Hungarian journalism and the establishment of the famous “press palace” in Budapest.

The Jews’ attraction to journalism derived mostly from the fact they resided in big cities, where press flourished. 20% of the Jews in late 19th century were living in Budapest, capital of Hungarian journalism.

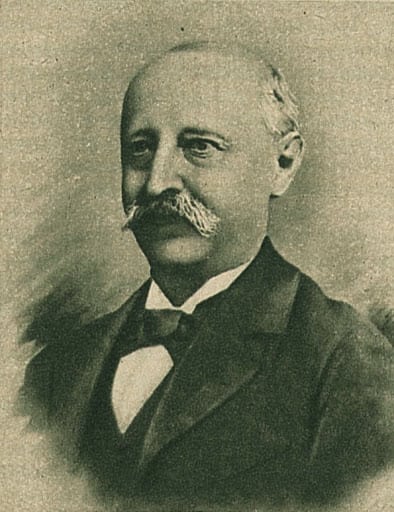

Prior to the emancipation, Miksa Falk introduced novelties into Hungarian journalism, such as deciphering system in order to avoid censorship; he actually created a unique new language that reflected popular speech. But only after the emancipation the great blast occurred, as new possibilities were opened for Jewish writers, who were considered the founders of Hungarian newspaper writing.

The most noticeable was Ágai Adolf, a genius satirists and a friend of Theodor Herzl, who worked as a reporter in the Neue Freie Presse. Ágai wrote witty feuilletons and was the forefather of political Hungarian satire, as well as a children’s author. Another prominent Jew in the 1870’s was publisher Légrády Károly, founder of the Pesti Hírlap political newspaper that unlike other political newspapers reflected the public’s views rather than interests of politicians. One renowned affair covered in Hungarian press during 1882 was the blood libel in the village of Tiszaeszlári, where a Christian girl went missing, and a Jewish slaughterer was accused of killing her and using her blood for his ritual needs. Her body was eventually discovered and it was proved that she committed suicide after her boyfriend left her. The affair, that echoed widely in Hungary and Europe, raised anger and frustration among the Jews and resulted in the establishment of two important Jewish weeklies with a social agenda, the Egyenlöség (equality), and the Múlt és Jövő, for Jewish Zionist youth.

In 1896 a new exciting format was introduced: the tabloids. Printed on cheap paper, with eye-catching headlines and small pages, it was distributed in the streets and published mainly sensations and scandals. The tabloids were almost entirely Jewish. The first one was Esti újság, established by editor Simon Zilahi and Barna Izidor, the first reporter in Hungary.

Then in 1904 Sandor Braun founded the sensational tabloid A Nap (the sun) and two years later, the “Az Est” was founded, which was the best sold newspaper in Hungary. The founder was Andor Miklós, who came from a poor Jewish family and had lots of siblings, and did not even finish elementary school, yet managed to become head of the largest press conglomerate in Hungary, Est.

The jewel in Jewish Hungarian journalism’s crown was famous “press palace” of Budapest. For the first time all journalistic labor was performed under one roof – writing, editing, proofreading, printing, marketing and distributing. Researchers agree that the press palaces were planned by vigorous Jewish entrepreneurs, the most famous of whom was Simon Tolnai, founder of Tolnai Világlapja, the first magazine in Hungary, with 100,000 copies during World War I, and the popular weekly Szinhazi Elet, by the Jewish publisher Sándor Incze.

Following the end of World War I, and Hungary’s loss of vast territories, the Hungarian press, and especially Jewish newspapers, started to decline. The rise of Hitler in Germany, 3 decades later, was the final nail in the coffin of the Jewish Hungarian press.