A well-known Jewish folk story, recounted whenever there is a need to emphasize what a lover of Jews Napoleon Bonaparte was, takes place during the failed campaign to the Land of Israel. It is told that Napoleon landed with his troops on Tisha B’Av. Upon hearing the Jews lamenting, he asked why, and when they explained to him that they were mourning for the destruction of their temple in 70ac, he said that if this people is mourning their temple after 1700 years, such a people so attached to their history, will indeed be restored to their land and have their temple rebuilt.

This tale – however special and flattering it is for the Jews – is historically inaccurate, to say the least. Napoleon’s army stayed in the Land of Israel between February and June, so it is hardly reasonable he was even in the area on Tisha B’av. Also, Napoleon did not show consistent admiration towards the Jews, it was rather a study case to the first significant emancipation that intended to include equality for the Jews, along with a new perception that that from then on, the Jews were subordinated first and foremost to the empire’s law, and committed primarily to what is best for the state.

Up until then, most of the Jews in France, as in Europe in general, lived in autonomous communities. But in the summer of 1789 the French revolution took place, introducing the values of freedom, equality and fraternity, as well as another concept: all citizens are subordinated to the state. Until the revolution, 40,000 Jews were living in France, a minority of whom were Sephardi Jews, French speaking and well integrated in society and the financial elite, with excellent relations with the monarchic authorities.

The majority of the Jews, some 30,000 were Ashkenazi Jews, descendants of Jews from German principalities, who resided in the Alsace-Lorraine area, close to the German border. They were Yiddish speakers, mostly poor families who congregated in their communities and did not aspire to assimilate in the French society as long as they could keep their autonomy. They lived peacefully and quietly.

A year after the revolution, when the national assembly of France discussed the Jewish minority’s status, they had no difficulties with the Sephardi Jews, as they already were part of the general society, which had many internal conflicts as it was – Catholic and Protestants, secular and religious, monarchists and republicans, to name a few. The Sephardim did not make any efforts to help their fellow Jews in Alsace-Lorraine get equal rights. Indeed, the Ashkenazi Jews were a whole different issue. The assembly had many disagreements as to what should be done with thousands of Jews in the French periphery, who weren’t keen to join the new national project. Eventually, in 1791 those in favor of integration won, and the Ashkenazi got equal rights and became citizens of the republic. Thus France became the first country ever to grant equal civil right to all its Jews. A new Jewish era has begun.

Meanwhile the Corsican consul Napoleon Bonaparte gained power in France. In 1804 he declared himself, with the blessing of the pope, emperor of France. He labored to expand the borders of France, which had far reaching consequences for the Jews. In Every place occupied by France, Napoleon declared that the Jews shall get equal rights as stated in the French constitution. On his campaign to the Land of Israel, a manifest was published that claimed that the Jews shall be granted an independent state in their historical homeland.

So was napoleon a Zionist? Not quite so. First, many doubt whether he really was the man behind that manifest. And even if he was, his motive was quite different. The attempt to conquest the Land of Israel was part of the effort to take Egypt, which was a territory that the French had hard time holding for long. Possibly, the French were trying to gain sympathy and support from the locals, therefore they released the manifest in favor of the Jews, hoping to make them their allies. Also, according to the French empire’s policy, it’s more likely that what Napoleon had in mind was a small puppet Jewish state ran by the French, rather than a genuine independent entity. It fits well with Napoleon’s attitude towards the Muslims at that time, in an attempt to get the Egyptians’ support, the French spread manifests praising Islam. Napoleon simply had a strong interest in the Middle East.

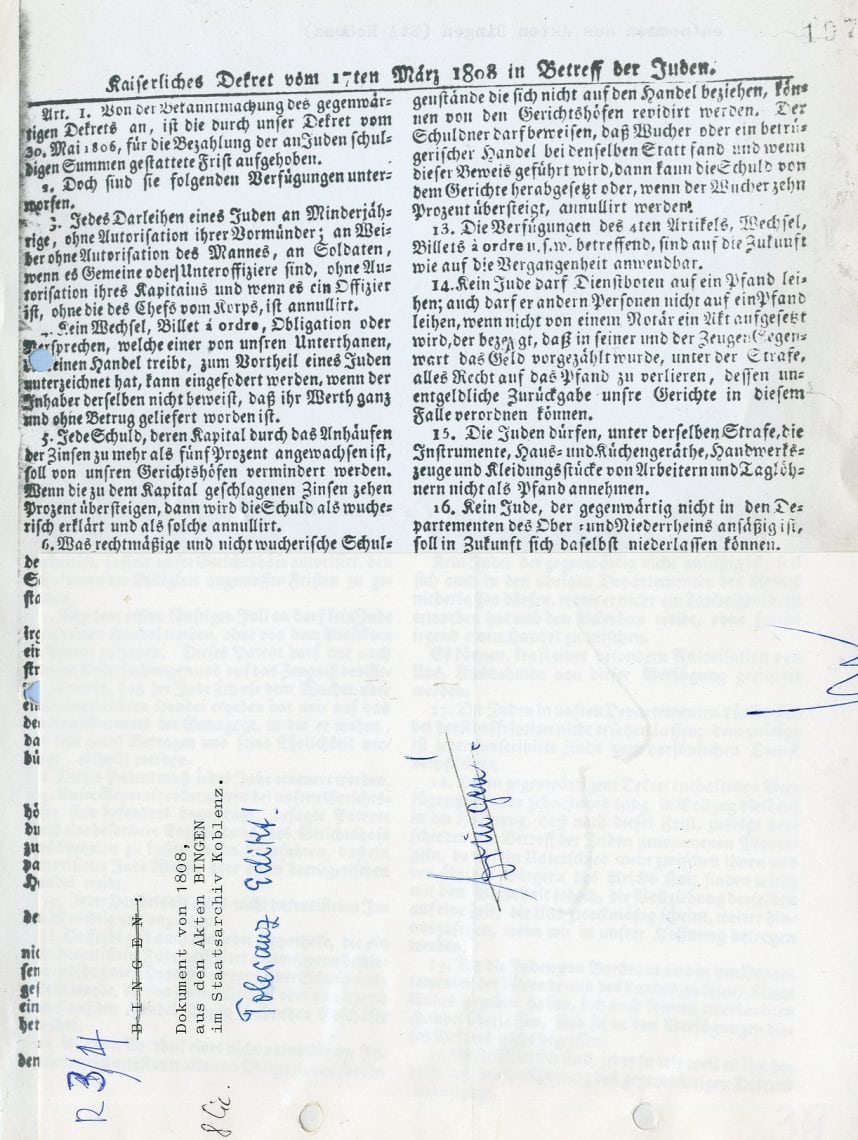

Meanwhile, back home things got complicated. In 1806 Napoleon decided it was time to reestablish the ancient Jewish Sanhedrin. In fact, it was a group of 70 rabbis subordinated to the French authorities, who ruled Halachot in the state’s name. Choosing the historical name “Sanhedrin” was Napoleon’s attempt to touch Jewish deepest sentiments, but in fact this institute resembled the modern chief rabbinate, who answers to the civil law. Apparently the rabbinate was invented by Napoleon.

In this case too it was his interest, not necessarily to empower the Jews but to subjugate the Jewish minority to the state, just like he did with ecclesiastical institutes, even though they were much stronger. He demanded that the Sanhedrin members’ rules matched the laws of the state. For example, regularization of issues such as army duties of the Jews, of money lending by Jews (a crucial issue for the Christians in Alsace-Lorraine) and even intermarriage between Jews and Christians.

Napoleon’s real feelings towards the Jews were, therefore, a complicated matter. Indeed, he promoted the equality – but only if they obeyed his rules and interests. Equality came second after sovereignty. In the long term, though probably unintentionally, he had great impact on Jewish history. In the occupied territories in Germany he introduced the idea of equal right for the Jews, which affected them well into the 19th century. The foundation of the Sanhedrin also had long terms impact, and today the existence of the chief rabbinate in Israel as well as everywhere else seem natural and is almost taken for granted. All thanks to the French conqueror who wanted to build an empire the world shall never forget.