The year was 1923, and among the main attractions for European football fans were English football leagues’ summer tours of the Continent. The gaps between the nation that invented football and its Continental neighbors were vast. The latter had yet to take its first steps in the game. No other all-star league trumped England’s until 1929, and the English leagues’ balls repeatedly landed in their opponents’ nets before wondrous eyes.

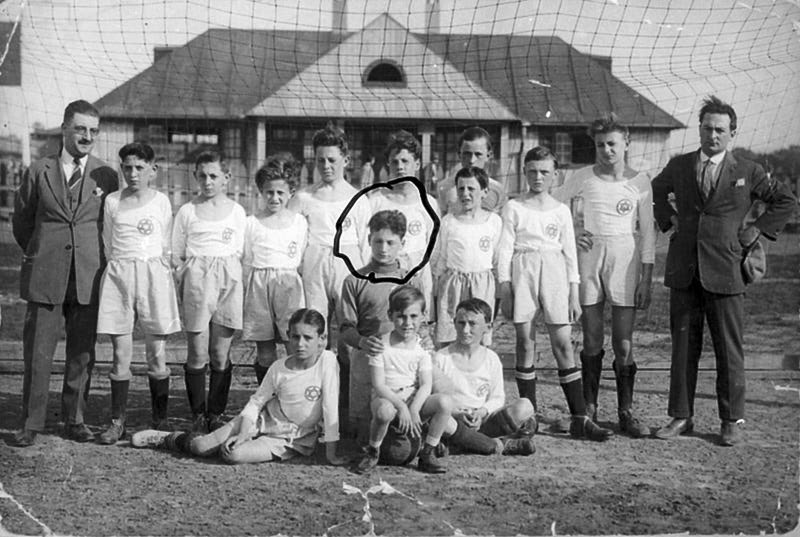

West Ham United, the runner up for the cup that year, traveled to Austria on one of those tours. Winning easily elsewhere, the Austrian league surprised spectators in a 1:1 tie with the unshakable Brits. The league was called Hakoah Vienna. The Hakoah members told their English counterparts at a joint meal that, as a Jewish league, they had to be tough. They faced a violent game from their opponents and lacking defense from judges. The English gentlemen invited them to a return match.

The match took place several months later in the Upton Park stadium in East London, and the result was a sensation. Hakoach became the first non-English league to beat England on British soil. The league not only won, but swept England’s eminent league in a score of 5:0. Alexander Nemes-Neufeld scored three goals.

The London Times revealed in stereotypes: “The Jews played scientific football.” LT noted – at a time when England was still an avid supporter of a Jewish homeland in the Land of Israel – that the league had trained physically to prepare them to emigrate to Palestine.

Hakoah truly was a Zionist league. The club’s prevailing spirit was Dr. Ignaz Kerner, a dentist who drafted many of the league’s players from Europe’s four corners. Famous cabaret writer Fritz Lehner managed the club with Kerner. Lehner organized the club’s annual fund-raising gala, which attracted many of Vienna’s Jewish elite. Two mega-celebs, Sigmund Freud and Franz Kafka, were among the league’s fans.

Austria paid little attention to the fact that this was a Jewish league, and at some point, forgot that a league that practically excluded non-Jewish players represented the nation. The Chancellor himself went to meet the train that carried the league home from London, and the victory in London was considered a major victory for Austria. Austrian football went pro one year later and Hakoah championed the professional leagues. But most of its fame was won on its tours of Europe and the Middle East. Its victories in Polish cities during a harsh anti-Semitic climate not only stirred broad adoration – but attracted Jewish youth to Jewish football clubs representing nearly every political movement. Hakoah also toured the Land of Israel and Egypt.

What the Austrians also forgot was that four of the goals, three by Nemes-Neufeld and one by Bela Guttman, were scored not by Austrians, but by Hungarians. Kerner didn’t really believe in a local draft. He searched throughout Europe for Jewish talent, and the place to find Jewish stars at that time was Hungary.

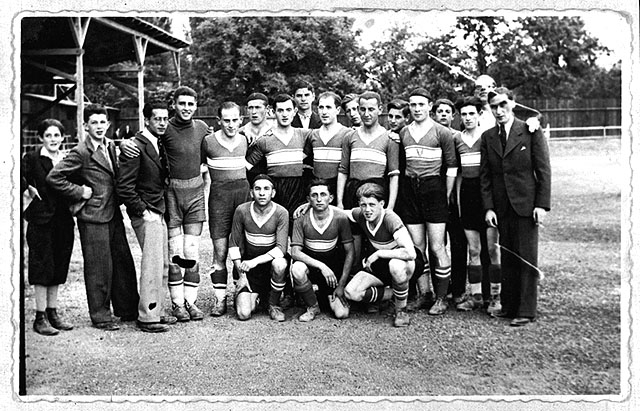

During those years, Hungary’s rise to a football power was meteoric. The strongest club in the land was MTK, which won nine national championships in a row, a world record that endured to the end of the century. MTK was not strictly a Jewish league, but most of its players were Jews. Guttman played for the league for a short time, but among its bigger stars were Joszef “Tsibi” Braun, Arpad Weisz, Gyula Mandi, and Zoltan Opata. There were eight Jews and Jews scored all seven goals in the Hungarian all-star league that crushed Italy 7:1 in Budapest in 1924. One of them was from Hakoah. The rest were from MTK.

Jews also joined MTK for political reasons. But they differed from those of Hakoah, who were profoundly influenced by Max Nordau’s Muscular Judaism address to the Second World Jewish Congress. A few years before that, a Hungarian-Jewish doctor and lecturer, Henrik Chuchny, wrote an article encouraging Jews to engage in sports – not to fulfill daydreams of a state in Palestine, but to integrate into Hungarian society. Thus, in a Budapest café on an afternoon in 1888, several intellectual Jews gathered to establish MTK – a Hungarian acronym for Hungarian Physical Culture Club.

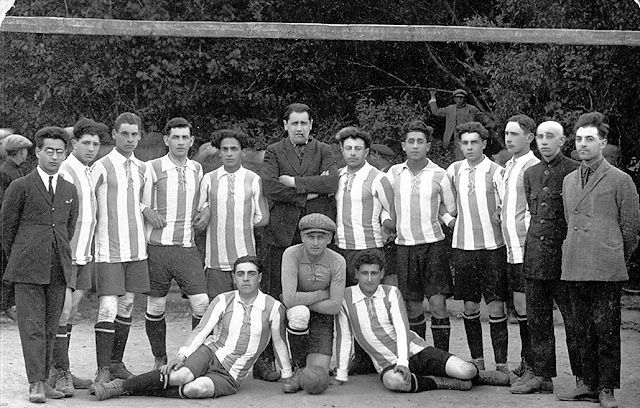

Whether Hakoah and MTK were the inspiration, this division of Zionist-Jewish and assimilationist-Jewish football clubs existed across the Continent. In Krakow, for example, the derby between the Zionist Maccabi league and the Bundist Lyotzhenka league was particularly heated. Many currently famous leagues that shroud their Jewish heritage were in the assimilationist camp of the Jewish-political spectrum, including Cracovia Krakow, Slavia Prague, Bayern Munich, Austria Vienna and apparently also Ajax Amsterdam.

Hakoah’s end was a mirror image of its ideology. After a round of matches in the US in 1926, attended by tens of thousands of spectators, many of its players decided – with some wisdom – that America was a much better place for Jews. They stayed in America and founded the New York Hakoah league that won the American cup in 1929. Hakoah Vienna was greatly weakened, and by the late 1920s, it was no longer a central player in Austria. The Nazis eventually shut down the league in 1938, and it was re-established in 2000. Bela Guttman was among those who left for the US, but he returned on the eve of the war in Europe to become one of football’s all-time leading coaches.

MTK’s winning streak was cut short in 1925. But it continued to be a central club and won three more championships before World War II. After that, the Communists divided the clubs among various government departments. MTK was assigned to the Secret Police. Gyula Mandi’s son, Atilla, told me cynically in 2008, “Then they really loved us. Secret police and Jews.”

The league continued to succeed and in 1964, finished in the European Cup Winners Cup. The league is still active and now plays in Hungary’s football federation. Jews are still notably represented in the league’s minor fan club, and the club preserves its attachment to Judaism. It will host the European Maccabiah this summer in its facilities.

What about Tottenham and Ajax? How Jewish are they?

Tottenham was not established as a Jewish club, but its location in North London, in the heart of the Jewish community, attracted a broad Jewish fan base. Before World War II, London’s press estimated that there were nearly 10,000 Jews among Tottenham’s fans, about a third of its average spectators. The concept of a “Jewish club” is not connected in public awareness with Jewish ownership. But premier-league clubs like Tottenham, Manchester United, West Ham, and Chelsea are owned by Jews. Arsenal was too, until not long ago.

Tottenham never had a significant Jewish player or coach (if we briefly set aside Israel’s “Rocket Ronny” Rosenthal, who played for them for three seasons). So, who decided that Tottenham was a Jewish club? The anti-Semites, of course, who are, entrusted with that. British fascist Oswald Mosley attacked Tottenham’s “Jewish sports mentality.” And occasional anti-Semitic events have occurred, in which fans, who typically support Chelsea or West Ham, call to Tottenham’s fans to go to the gas chamber. Tottenham supporters call themselves Yids and take pride in the Jewish connection, however slight.

Tottenham’s “Jewish” rival in the semi-finals this week, Ajax, has a somewhat similar Jewish connection. There were a few Jews among the club’s founders and early supporters, because football was then a middle-class sport. Associated with the club is the tragic story of Eddy Hammel, an American-Jew who played for Ajax in the 30s. He was trapped in Europe during the war and killed in Auschwitz.

But as in Tottenham, Ajax’s fans adopted their own Jewish identity. They wave Israeli flags, sport Stars of David, and sing their version of Hava Nagila in the stands – in part, to express liberal Amsterdam and its significant Jewish history in defiance of peripheral Netherlands’ Christian conservativism. The strains of “Super Yuden Ole Ole” can be heard in the stands, to the frequent chagrin of Amsterdam’s Jews. The league is sometimes called “The Pride of Mokum,” the residents’ nickname for Amsterdam, which hails from the Hebrew “makom” for place.

The other Jewish connection can be found in the personal stories of some of the league’s stars. The legendary Johan Cruijff, Holland’s and Ajax’s greatest player of all time, worked for Jewish merchants in his youth – and sometimes as a “Shabbos goy.” He married a famous Jewish diamond dealer, whose son Jordi successfully managed Maccabi Tel Aviv for several years. Another Ajax player with a surprising Jewish heritage is Edgar Davids, a dark-skinned native of Surinam whose grandfather was Jewish. There were few Jewish players of a professional level on Ajax after the war and the historical role that they played in the outstanding club was insignificant. They were Szaak Swart and Daniel de Ridder, who also played for Hapoel Tel Aviv.