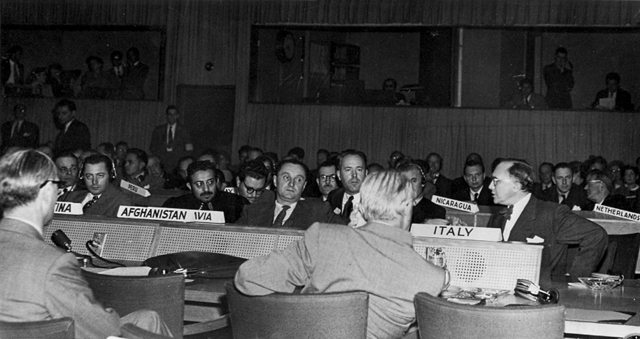

The Jewish People are characterized by dualities: exile and redemption; slavery and liberty; Holocaust and revival; calamity and heroism; restraint and uprising; Memorial Day and Independence Day. This duality was, in fact, the historical backdrop behind the United Nations’ final vote in favor of the Partition Plan for Palestine on November 29, 1947 in the U.N. General Assembly Hall in Flushing Meadow, New York. The period that preceded this happy occasion was a low point in the Jewish Yishuv. At that moment no Jewish leader dared hope for the declaration of an independent Jewish state.

After World War II, Britain’s Labour Party prevailed in the country’s elections. The party touted a pro-Arab policy that suppressed Jewish national aspirations by limiting land purchase ability in Eretz Israel and rerouting Jewish refugee ships bound for the Holy Land to Italy and Cyprus.

The Zionists reacted with armed resistance and the British responded with force via the Black Sabbath of June 29, 1946. On that occasion the British arrested 2,700 leading Zionist figures. It was in the wake of that dark hour that Nahum Goldmann arrived at an unexpected plan that changed history.

Born in Vishnyeva, Lithuania in 1895 and raised in Frankfurt am Main, Nahum Goldmann’s heritage paired Jewish Eastern European tradition with enlightened German elitism. A jurist, Chair of the World Zionist Organization, founder of the Judaica Encyclopedia and Beit Hatfutsot Museum, Dr. Goldmann was first and foremost a non-conformist statesman and model creative thinker.

In July 1946 Britain and the U.S. issued their joint Morrison-Grady recommendations. Although these recommendations granted 100,000 certificates of entry to Palestine to Jewish refugees and displaced persons, the Morrison-Grady plan ignored the possibility of an independent Jewish state. The plan’s primary recommendation was to divide the country into Jewish and Arab autonomies that would remain under British supervision.

On August 3, 1946 a three-day assembly of Zionist leaders, including Nahum Goldmann, was held in Paris. Deeply affected by both the Morrison-Grady plan and the Black Sabbath, the participants were tense and the atmosphere desperate. After two days of feverish, emotional debates the participants were confused and misguided. David Ben Gurion, head of the Zionist movement, was having trouble conducting the relentless discussions. Some said he sounded incomprehensible, delivered vague messages, and seemed almost helpless.

It was in this bleak moment that Dr. Goldmann rose to the occasion. “I have been told by my contacts in the American government that President Truman is having second thoughts about the Morrison-Grady plan. Our time is running out; if we do not make a final decision right away as to our realistic demands, we might miss a one-time historical opportunity.” The crowd was tense. They all knew that by “decision” Goldmann meant the crucial decision to divide the territory. The Zionists had been avoiding this since the Biltmore Conference of 1942, during which it was declared that the Jewish national home must include all territories from the Jordan river to the Mediterranean sea. The Zionist strategy up until this point had been to consider partition only if the U.N. suggested it. They did not want to bring it up themselves as a negotiable option; to do so was near heresy.

At 1:30 in the afternoon on August 5, 1946 the Zionist leaders hastily composed a proposal that Goldmann himself rushed to Washington to deliver. In his briefcase, Goldmann carried the Partition Plan. Upon his arrival he handed it to the Americans, and soon after President Truman cancelled the Morisson-Grady recommendations. The UNSCOP report followed, its recommendations leading to the November 29th vote. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Dr. Nahum Goldmann had no public relations team in his corner. His portrait cannot be found on any currency, and his name is not commemorated by streets or monuments. Historian Yigal Elam claims that “Goldmann’s finest hour was when he rescued the disoriented Zionist leadership from the dead end to which they were heading after the Black Sabbath and forced them to make a crucial courageous bright move that made a historical breakthrough – giving up territories of the Land of Israel – perhaps the most important move in the history of Zionism.”

Goldmann is scarcely mentioned in the history books. His colleagues thought of him as an outsider, and world leaders saw him as the typical cosmopolite Jewish lobbyist. But as we commemmorate 70 years of the historical U.N. vote that led to the creation of the State of Israel, we should pay tribute to a man wise and daring enough to know that sometimes survival is more important than territory, that true politics necessitate letting go of dogma, and, perhaps most critical of all, that at crucial junctures it is best to compromise in order to make a deal.