Long before the Israeli Mossad became the best espionage organization in the world, Jewish spies in Israel stripped off and donned disguises, crossed enemy lines and brought back quality intelligence – intelligence that did not come under the heading of “the public’s right to know.” Among the most important, least well known and most forgotten of them was one whose life and activities nonetheless surpassed all imagination. The bohemian Jerusalem businessman, Israel’s leading insurance agent and a poet, was also among the leaders of one of Israel’s largest World-War-I era spy networks.

Alter Levin was born in Minsk in 1883 to a religious family, who made aliya to Palestine and settled in Jerusalem when he was two. His father Morris, a man of means, devoted himself to his son’s education and provided him with tutors in all subjects including science, literature, art and languages. As a youth, after studying in Rabbi Haim Yehoshua Kosovki’s Etz Haim Yeshiva, he joined his father’s business and became the head of the Jerusalem branch of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. He went on to become Israel’s leading insurance agent and open the “Alter Levin General, Life, Disaster, and Fire Insurance Office.”

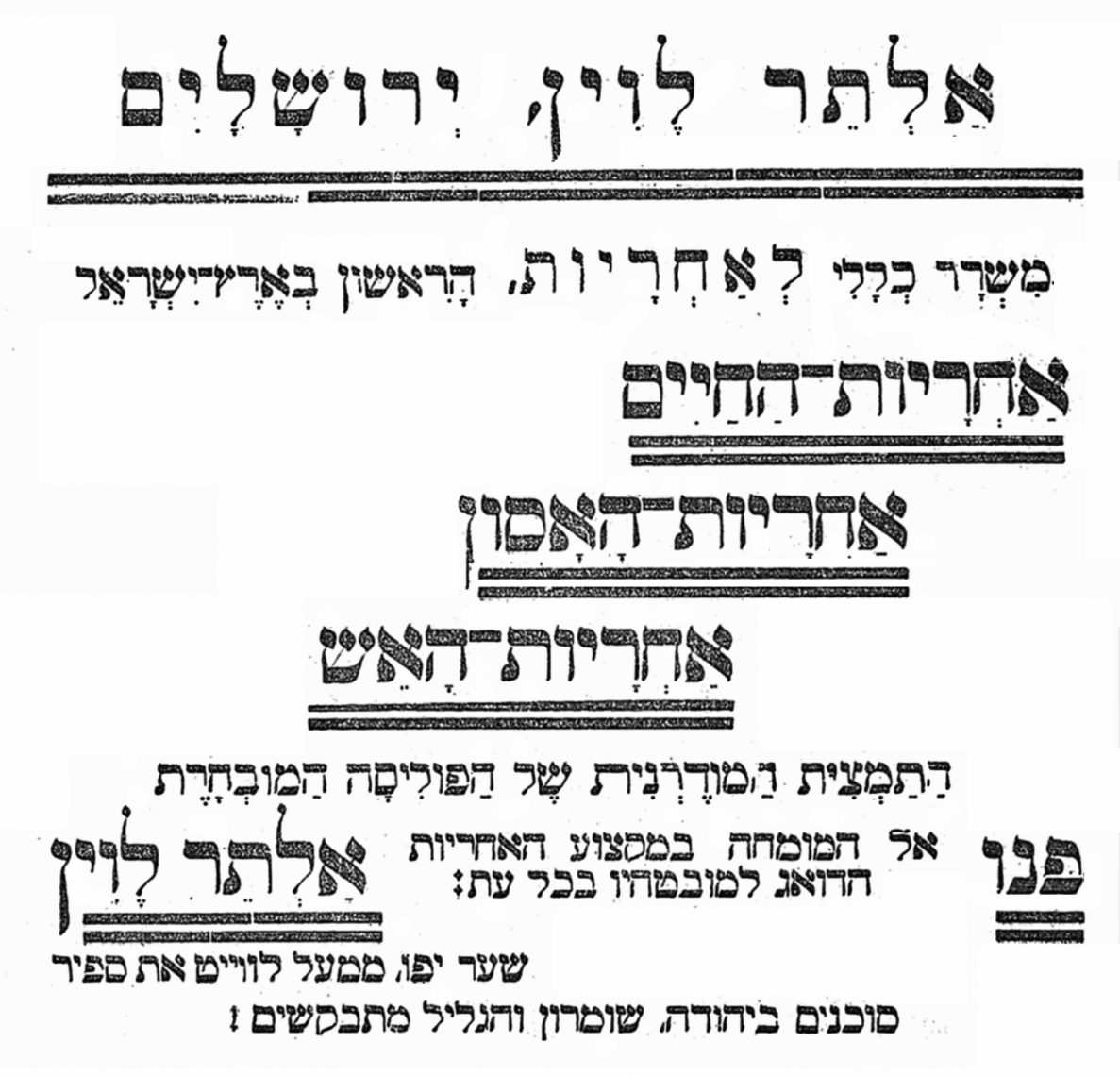

The office of the man local papers dubbed “the Insurance King” was located in Jerusalem’s Jaffa Street Sensor Building. It was considered one of the poshest offices in the Middle East, and at its height, employed seven workers and dozens of agents. Levin adopted cutting edge marketing strategies, and marked the homes of clients with signs called “fire signals.” His company represented dozens of American and French clients, including artist Nahum Gutman, who paid him in paintings. Half a century went by before Levin’s grandson, Mordechai Munin, reopened the agency under the name “El-Ad,” which is still operating in Jerusalem.

But Levin did not only view the world through the hole of Israel’s iconic “grush” penny. He blended the seemingly contradictory material and spiritual, publishing poems in Havatzelet, Hapoel Hatzair, and Haaretz under the name “Assaf Halevi, a Man of Jerusalem.” An anthology of his poems, “Megillat Kedem,” which reveals a naïve love of Jerusalem’s landscapes and characters, earned broad praise from critics including the celebrated Rachel (Bluwstein) the Poet.

Pleasing and fascinating as these anecdotes are, Levin’s legacy is etched in his great contribution as a spy and underground agent during World War I. Professor Eliezer Tauber righted a historic wrong in exposing this affair in 1991, 60 years after Levin’s death. Tauber uncovered a diary that proved to be that of Aziz (Akyurek) Bey, the director of the Ottoman 4th Army’s Security Service. Bey wrote in his diary that Levin’s business acumen enabled him to form ties with key figures in the highest ranks of the Turkish government. In time, his colorful personality, fluent Arabic and adoption of Turkish attire and customs endeared him to Djemal Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Syria and the Land of Israel. Levin became Pasha’s right-hand man and official aide, a role that gave him access to the Ottoman Empire’s deepest secrets.

Aziz noted that when World War I erupted, Levin played a central role in reporting strategy and tactics to British intelligence. Levin used his insurance agent story as a cover and his Jewish employees as spies on behalf of the British. When Levin’s insurance agents visited the homes and military and government institutions of Turkish dignitaries to sell them insurance policies, they collected information about the army’s movements, the dignitaries’ social and financial status, and prevailing winds in Ottoman society.

Aziz Bey cites Levin as a key player in bringing down the Ottoman Empire. He stresses the intelligence that Levin provided to the British regarding the Ottoman campaign to conquer the Suez Canal, believing that to be the central reason for the campaign’s failure. Nothing less.

Jewish prostitutes placed by Levin in Jerusalem’s many brothels during that period were vital to his spy network. When German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman officers encountered, played cards, and drank and ate with the women in these brothels, they shared their adventures and achievements on the battle field. Prominent among these spies was Lydia Murdoch Simanovich. She revealed in police investigations, after she was detained in a raid, that she was in Levin’s employ.

Her disclosure forced Levin into hiding in the home of Halil A-Schahini, his close friend and Arabic teacher. The Ottoman police cornered Levin after surveillance on his mother-in-law found her bringing Levin food in A-Schahini’s home so that he could continue to keep Kosher. Levin was immediately arrested, handcuffed an brought to trial in Damascus, where he was sentenced to death. He expressed a last wish for a “cigarette.” By miracle or palm-greasing, his sentence was reduced and after a year in prison, he was freed to return to Jerusalem following a prisoner exchange. In Israel, Levin returned to thriving in business and mainly in insurance. The man who customarily introduced himself as “the King of Life and Death,” built a luxe home in Jerusalem’s new Romema neighborhood, where he housed his collection of over 200 works of art. He eventually bought the home of Jerusalem’s acclaimed ophthalmologist, Dr. Abraham Ticho.

Levin’s death was not surprisingly tragic: On Sukkot Eve in 1933, he was found hanging from a palm tree in the yard of his Romema home. There was no suicide note or letter of explanation and the mystery has yet to be solved.

The question is why every schoolkid in Israel knows the legendary and broadly documented story of the Nili spy network and its heroes, Sara and Aharon Aharonson, who spied on behalf of Israel during the same period – while Levin’s spy network is relegated to the shadows of forgotten history. Levin’s story could shed light on others. Take the ZZW Jewish Military Union in Poland and their leader Pawel Frenkel, whose memories have nearly vanished from Israel’s national memory despite their critical part in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Why did Mordechai Anielevicz’s Jewish Fighting Organization get all the glory in that rebellion – while people like Hillel Kook and Ben Hecht, who saved thousands of Jews from the claws of the Nazis claws in the Holocaust, remain anonymous to most Israelis? It turns out that in Alter Levin’s case as well, if you want to make history you had better be in the right camp of history’s agents.