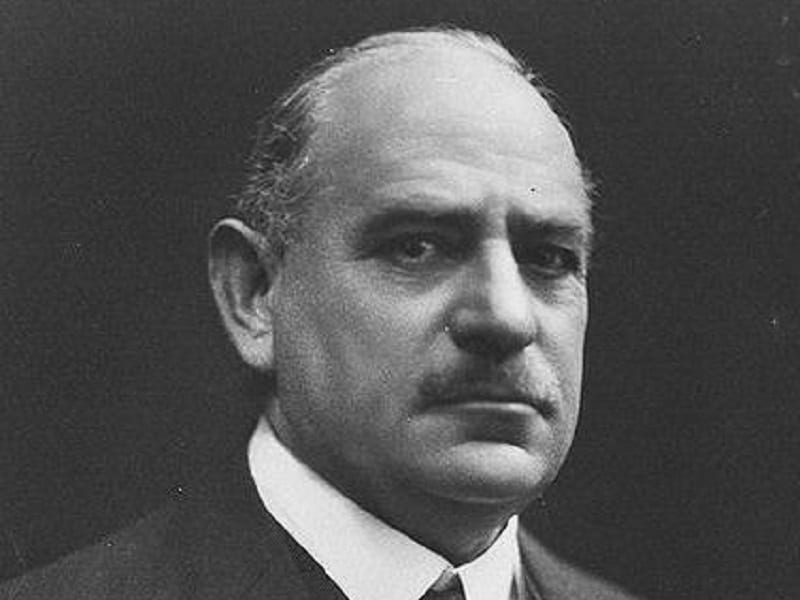

When John Monash arrived in Cairo from Australia during World War I, he had no formal military training. But he did have an extensive education, and notable achievements as a civil engineer. The son of Jewish immigrants to Australia, Monash earned academic degrees in law, art, and engineering. He was a reservist officer in the Australian intelligence corps and a successful engineer-businessman as well.

Monash proved to have ability to take a broad look at the catastrophic errors that turned the battlefields of the war into some of the greatest bloodbaths of military history. This would make him the most influential general in the Great War—the man to untie the bleeding knot that was the Western Front.

Monash’s first battlefield experience was in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign, where he impressed the British command by evacuating 45,000 soldiers. However, by that point anti-Semitic rumors had begun to spread, accusing Monash of being a German spy. These rumors were bolstered by the fact that Monash’s parents lived in Germany, next to the German Chief of Staff, Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff.

In 1916, Monash was deployed to the Western Front. He had won the cautious respect of senior Australian officers, but suspicions about him continued to swirl: “We do not want Australia represented by men mainly because of their ability, natural and inborn in Jews, to push themselves,” wrote the official Australian Military Historian, Charles Bean. Bean had conspired with other officers and journalist Keith Murdoch—the father of international media mogul Rupert Murdoch—in an attempt to remove Monash from his position. Historian Geoffrey Serle called the anti-Monash campaign “perhaps the outstanding case of sheer irresponsibility by pressmen in Australian history.”

But when Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes visited the front to examine the matter, he discovered that the reality was dramatically different from what had been represented to him. Soldiers and lower officers admired Monash. Although Monash did not lead them from the front, and instead organized and sent instructions for battles from headquarters, he was extremely sensitive towards the loss of life. Monash would rapidly end futile infantry charges, and organize warm meals to be delivered daily to the front lines.

Monash had also led the Anzacs to impressive victories at Messines and Broodseinde. His meticulous planning raised morale among soldiers, who until that point had seen little progress after three years. War correspondent F.M. Cutlack stated: “He saw everybody; he forgot nothing; he left nothing to chance.”

With growing confidence, Monash would now redesign modern military strategies. Infantry soldiers would no longer be used to protect machines. Rather, they would advance behind tanks, under the cover of the air force and artillery, in order to secure positional gains.

The battle of Hamel, France, sealed Monash’s reputation as a tactical mastermind. He designed a 90-minute plan that gambled on the use of tanks and artillery by the advancing infantry. That plan delivered a victory in exactly 93 minutes, and Hamel is considered to be the first combined arms battle in history. Ironically, it would later provide the blueprint for German military tactics in World War II.

At the second battle of Amiens, which was also led by Monash, the Anzacs charged first, destroying the German artillery and paving the way for a decisive victory. Ludendorff described it in his diary as “The darkest day in the history of German military”. King George V of England came personally to the battlefield to knight the Jewish General. It was the first such act of gratitude by a British Monarch in 200 years.

Back in Australia after the war, Monash would further serve his nation by leading major electricity distribution projects throughout the countryside. More significantly, he would become an advocate and unofficial representative for the Anzac veterans who struggled in civilian life.

His funeral procession to Melbourne’s Jewish cemetery in 1931 attracted an estimated 250,000 people, the largest crowd ever seen in Australia until that point.