Throughout most of Jewish history, Jewish scholars and authors contributed in all genres but one: they wrote Halacha and Agadah, poetry, lamentations, songs of joy, holidays poems, ethics, Kabbala and “Sod” (mystery) literature – you can find Jewish authors everywhere in written culture. But there was one field which they have been avoiding until the 19th century – historiography. Unlike their neighbors, whether Muslim or Christian – Jews avoided writing chronicles of their history, and used to describe important events within other written genres.

This tendency did have, however, one interesting exception – no, we are not going to tell you about Yosef Ben Matityahu (aka Flavius Josephus), the 1st century historian who left us famous records, but rather about a 16th century author, Azariah dei Rossi (Azariah of the Red Family), who lived in Italy and overwhelmed the Jewish world with his unique historical essay, Me’or Enayim (Hebrew, Light of the Eyes).

Azaria was born in the beginning of the 16th century in Mantua, Lombardy and spent his entire life in northern central Italy. His ancestors were noble, and according to the family tradition, descendants of the original Jewish settlers in the Roman empire. He received broad education and apparently started to work as a money lender, like most of the Jews. At some point he entered the flourishing industry of printing. Then a most traumatic event caused Azariah to do what no Jew has done before.

In 1570, a strong earthquake has struck the area of Ferrara. For over two days, on a weekend, there were several quakes that caused dozens of casualties, and destroyed hundreds of houses. Filled with horror and awe, Azariah wrote: “one loud temblor lasted for half a tenth of an hour, destroyed buildings, broke walls, filled all houses with rifts and shreds”. His own home too was completely destroyed. After the earthquake, as he walked through the ruined town, he met a Christian acquaintance and they started to discuss the Letter of Aristeas, an ancient Jewish essay in Greek about the Septuagint – the Greek translation of the bible. The Letter of Aristeas was appreciated and preserved by both the Jews and the Christians, and Azariah’s friend asked whether it was ever translated into Hebrew. While replying that it was not, Azariah made up his mind to translate it himself. Within less than a month he completed the translation of the entire essay to Hebrew.

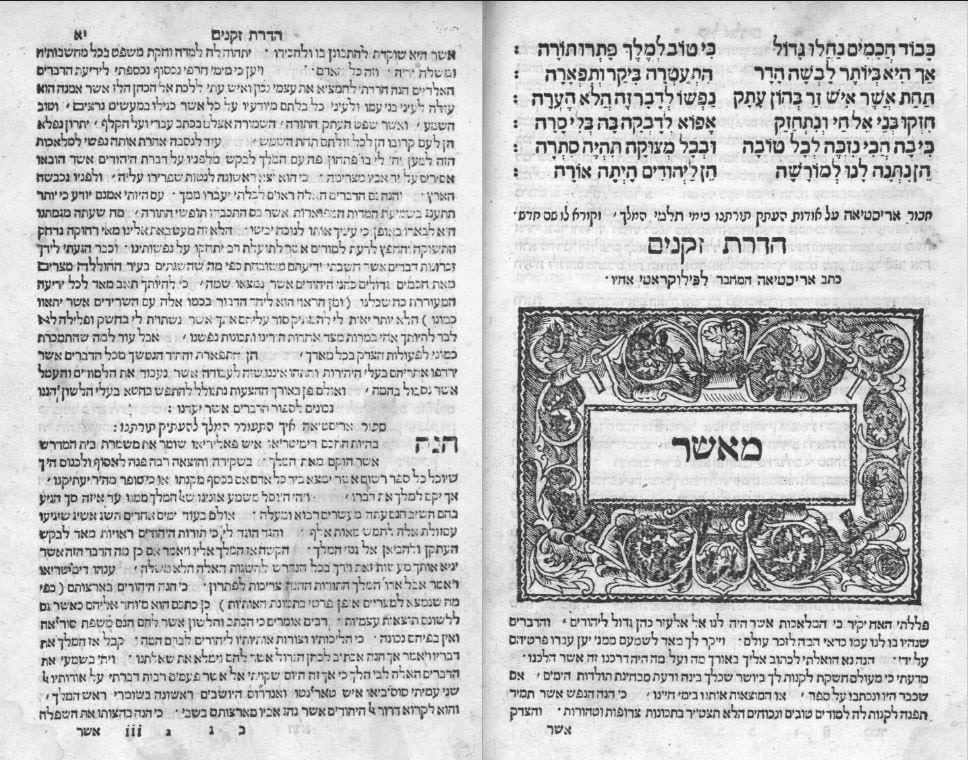

After completing this important task inspired by the earthquake, Azariah went on to compose a unique odd essay called Me’or Enayim (Light of the Eyes, in which the two first parts tell the story of the earthquake, as a proof to the might of God, and the translation of the Letter of Aristeas. The third part, though, called Imrey Bina (Words of Wisdom) is the most intriguing: Azariah simply decided to write down the history of the Jewish people. He unfolded the stories of Jewish sects in the 2nd temple period, wrote about Hazal (our sages), and also about Emperor Titus, among other topics.

This was highly unacceptable at that time. Even when Jews had to refer to chronicles of events, they usually relied on traditional rabbinical texts. Azariah was the first who used sources such as Yosef Ben Matityahu as well as the books by the Hellenic Jew Philo of Alexandria. Though both were Jews, the works by Yosef and Philo were not translated and only the Christians related to them and preserved them. Using these sources, as well as historical ecclesiastical records in order to form a first structured historical chronicle – drew much attention to the pioneering book of Azariah. Azariah would not rest, he carried on with his historical initiative. He used a mediaeval chronicle called Josippon which was a “good” Jewish adaptation to Ben Matityahu, and insisted that it was a latter version, rather than the genuine work. In some cases, he felt that Hazal’s chronicles contradicted his calculations – and specified it. He claimed that things written in Sages literature weren’t necessarily facts and no practical conclusion should be drawn from them.

Naturally, this last statement irritated many rabbis and scholars. Shortly after the book was printed in 1574, a few Italian rabbis published furious sermons against Azariah, and were later joined by rabbis in other European countries. In the land of Israel, the book reached rabbi Yosef Caro, who was appalled too by the Azariah’s arguments about the questionable chronology of the Sages. The Maharal of Prague too criticized the essay and it kept stirring the rabbinical world for two more centuries; once in a while rabbis continued to come out against it.

Azariah never meant to defy the Jewish world in which he lived in. He was no rebel nor a reformer of any kind, nor a marginal or odd man and author. His books are full of praises to God and also to the Sages. We need to examine the context of his work – he lived in central cities in Italy during the Renaissance, in a time when a blast of printed books of all kind was all around him, a time when educated Jews were introduced to books and opinions they have never seen until then. He wished to make use of all the knowledge he had, and to form organized chronicles, and for that purpose he respected all Jewish sources.

It is especially interesting to view much latter reactions to this story. Towards the end of the 18th century, enlightenment started to spread in Europe. The Maskilim asserted that Jews must stop being aloof and must gain general education, including biology, geography, anatomy, and mostly – history. They started to search for historical figures of identification, some kind of “proto-Maskilim” that match this new self-image. The figure of Azariah met their needs perfectly. In modern Jewish historiography, he was considered an important trailblazer, and until today his books are still subjected to arguments and researches.

Further reading:

כתבי עזריה מן האדומים, בעריכת ראובן בונפיל, הוצאת מוסד ביאליק , 1991