It was the same old story every weekend. On our way home from Shabbat dinner at my sister’s house in Haifa’s Ahuza neighborhood, my grandfather – may he rest in peace – would stop in a tiny alley to bow down at length to a street sign. This peculiar ritual took many seconds to complete, before my grandfather continued on his way as if nothing had happened.

When in first grade the shapes of letters began to make sense to me, I read the sign for the first time: “Isaac Babel, Jewish-Russian writer.” Not long after that, my grandfather presented me with a collection of short stories entitled, “The Odessa Tales,” and demanded that I “Read!”

My aging Jewish grandfather was more than mischievous. He presumed that the tales of crime penned by his beloved writer would teach me a thing or two about life. He secretly hoped that I – like he – would fall in love.

Just as Damon Runyon depicted the backstreets of New York and Henry Miller illumed the dark side of Paris, the City of Light – Isaac Babel was the people’s poet of Odessa. No other writer employed his zest, love, and talent (what talent!) for exposing the mysterious charm of the city of Jewish immigrants on the shores of the Black Sea.

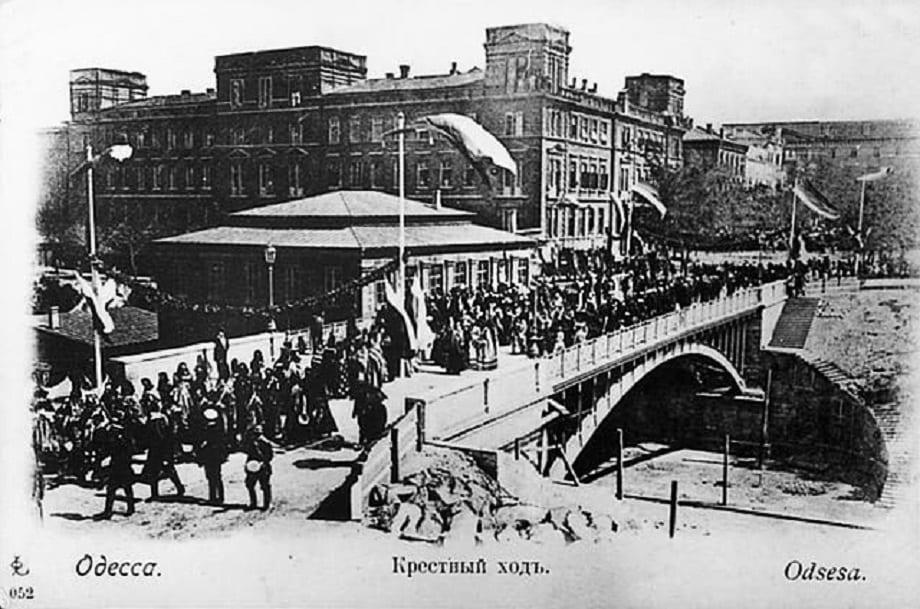

The Jews of Odessa adored their city. They called her “Mama Odessa,” and she unconditionally returned their love. Pubs, bustling beaches, advanced institutions of education, a center for modern Hebrew culture, and a network of Jewish newspapers in Hebrew. In the late 19th century, Odessa was the place to be. A secular Jewish city that inflamed the imaginations of Hassidim who wrote that “the flames of hell are burning 40 versts from Odessa.”

The Jews flocked to Odessa in droves. In 1854, 54,000 Jews lived in Odessa. Less than 30 years later, their population had doubled to 124,000 – about a third of the city’s residents. Most of the Jews – like Ahad Ha’am and Bialik – were immigrants who fled the jail that was the shtetl. Odessa was their island of sanity, the model of a future, secular Hebrew city. No wonder that another one-time Odessa resident, Meir Dizengoff, sought to model the nascent Hebrew city of Tel Aviv after Odessa.

As an Odessan native, Babel was less concerned with ideology. He was only committed to portraying the “earthly Odessa.” To that end, he dove to the depths of the city’s sewage to extract pearls and diamonds. Babel presented characters in his stories that no one before him had dared to expose. His heroes were smugglers and thieves, prostitutes, pimps and gangsters. All of them Jews who frequented the pubs, brothels and synagogues of Odessa.

When Shprintza, in “Tevye’s Daughters: Collected Stories of Sholem Aleichem,” experienced unrequited love – she drowned herself in the river. Baska – the heroine of Babel’s similar story – also considered suicide when she was spurned by her beloved. But a local brothel owner offered to match Baska up with a Jewish gangster named “Benya Krik,” who would also take out her beloved and his family. That was – if you please – Babel’s answer to Rabbi Hillel’s Torah on one foot. No more tragic and tortured Jews – but Jews who avenged when necessary.

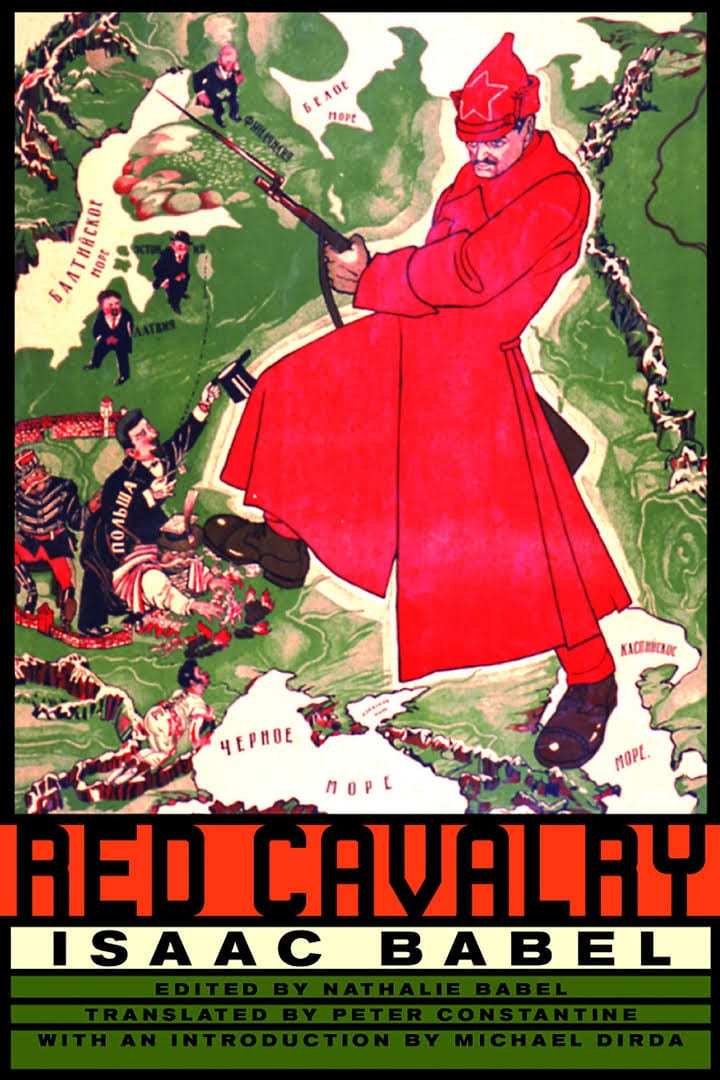

Babel did not limit himself to portraying the city of his birth. In the Spring of 1920, he joined – as a writer – the Red Army’s Cossack Cavalry, in the war with Poland. He was deployed with illiterate, bloodthirsty Cossacks. Imagine an intellectual, four-eyed Jew alongside hotheads riding bareback on wild and galloping horses, shooting anyone and everyone, in their way. To be accepted in the Cavalry, Babel was forced to nearly slaughter a goose with his bare hands and stomp on the miserable creature until it breathed its dying breath. His pre-battle wish was, “God, give me the strength to kill another man.”

Babel documented the horrors of war, and the heroism of the Cossack fighters. He reworked his war diary into a collection of short stories entitled, “Red Cavalry,” describing the absurdity of war. That book granted Babel fame and high praise, and literary giants like Gorky offered him shelter. Babel was declared the most sophisticated Russian writer of the 20th century.

But one man was underwhelmed by Babel’s depictions of battle. Komandarm Semyon Budyonny’s, the commander of the Cossack’s 1st Cavalry Army, was not – to say the least – into the Jewish writer’s satirical, anti-war style. “He writes in the voice of a terrified, old woman,” wrote Budyonny in a Communist Party newspaper. “He’s gripped with terror at the sight of a hungry soldier.”

From that moment, Babel was living on borrowed time. He knew very well that if the Soviet machine had marked him, it was only a matter of time until he found his way – at best – to an isolated, far-flung gulag. While it took a few years, the Secret Police finally knocked on the door of his Moscow apartment in May 1939. He was detained and executed on January 27, 79 years ago last week.

Abraham Shlonsky’s Hebrew translation of “The Odessa Tales” was first published in 1963. My grandfather, whose family came from Odessa, saw the book in a bookstore on Hehalutz Street in Haifa. He bought the last remaining copy. On June 14, 1964, the Haifa Municipality led by mayor Abba Hushi, convened to officially name Alley #759 in the Ahuza neighborhood after the Russian-Jewish writer Isaac Babel.

The peerless writer about the backstreets of life was granted a backstreet in his name in the city of my birth. Years passed and my grandfather went to his final reward. My sister still lives next to “Babel Lane,” and whenever I pass there, I bow deeply to the street sign – in honor of my grandfather’s favorite writer. And my own.