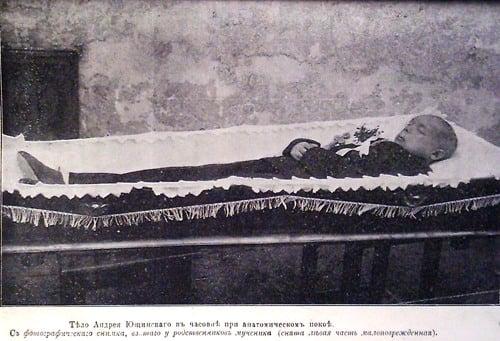

On the spring morning of March 12, 1911, 13-year-old Andrei Yushchinsky left his house to go to school, just like he did every morning. But when he didn’t come home that afternoon, it turned out that he hadn’t made it school either. On March 16, his mother and stepfather contacted the editors of the local newspaper and asked them to publish a notice about a missing child. Four days later, Andrei’s body was found in one of the caves located in the outskirts of the city of Kiev. His hands were tied and he had stab wounds all over his body.

The Kiev police launched an investigation. The immediate suspects were his parents, his mother and stepfather, who would have gotten the inheritance that was awaiting Andrei in a bank account opened by his biological father. They were brought in for questioning twice, and on both occasions were released due to a lack of evidence.

After that, the investigators checked another possibility, according to which the boy was murdered by a local gang of robbers because he threatened to tell the police about the goods they had stolen. But the case reached a dead end. No witnesses were found and there was no corroborating evidence.

During Andrei’s funeral, leaflets were handed out to those in attendance, which claimed that he had been tortured to death by Zhyds, namely Jews. He had been tortured so they could use his blood to make matzos for the upcoming Passover holiday. The same sick and age-old blood libel. The leaflets were signed by extreme right-wing antisemitic organizations that operated out of Kiev. At first, that version of the incident sounded preposterous, but as time passed, dozens of anonymous letters were added to the case file, which warned that the murder had in fact been committed by Jews.

On April 29, about six weeks after Andrei’s death, the extreme right-wing faction in the Duma (Russian Parliament) in Moscow raised the matter in an official parliamentary question and demanded answers. They wanted to know what plan of action the government had for eradicating future murders committed by Jews for ritual purposes. One member of the Duma, Markov, announced that “if this time, as well, the government fails to take steps which will make it possible to blame the Jews for murdering a Russian child, it will end in a pogrom and all the Jews will die.”

Like in the past, this time the antisemitic propaganda had a clear aim and was not spontaneous. Elections to the Duma were scheduled to be held within the year. The incitement was supposed to help the right defeat the liberal and democratic factions and win a majority of the votes. The Minister of Justice, Shcheglovitov, kept the Prime Minister, Stolypin, advised of the situation and dispatched a special team of investigators to Kiev. Additionally, he sent a telegram to the district prosecutor of Kiev and demanded that he “closely monitor the conduct of the investigation.” That request came as no surprise because that very same prosecutor had previously informed Shcheglovitov that, in his opinion, it was highly probable that the boy had been murdered by Jews for ritual purposes. Later on, with a little pressure ‘from above,’ forensic evidence was also found following the autopsy, which backed up that version. Allegedly, the motive for the murder was clear. All that was left was to find the killer.

Menahem Mendel Beilis worked at a brick factory near the scene of the murder. Zaitsev, the owner of the factory, was also Jewish. That coincidence immediately raised suspicion among the antisemitic organizations in the city, which launched an investigation of their own and made that information available to the special team of investigators who had been dispatched to Kiev by the Minister of Justice. Suddenly, witnesses appeared who described “a man with a black beard” who had chased after Andrei and dragged him to one of the furnaces at the factory, where two other men “wearing strange clothing” were waiting for them.

Beilis was brought in for questioning, but denied having any connection with the incident. It also came to light that neither he nor the factory owner were religious Jews and did not dress like ones. Beilis’s wife, Esther, told the investigators that her husband did not observe the Sabbath and did not celebrate Jewish holidays because he had to work around the clock to support his five young children. The investigation reached another dead end and Beilis was allowed to go home.

Kiev was at the time preparing for a visit by the Tsar and his entourage. The police did everything in their power to guarantee the safety of the royal family and calm the tense atmosphere in the city, which continued to be highly explosive. People belonging to extreme right-wing groups in Kiev and to the extreme right factions in the Duma threatened to escalate the situation and carry out pogroms, seemingly leaving the Kiev police with no choice but to arrest Beilis in order to “ensure his personal safety” – as they put it.

In the meantime, ‘new evidence’ was building up against Beilis, who was still in protective custody. His so-called ‘cellmate’ reported that Beilis had confessed to committing the crime. After being tortured, Beilis himself confessed to murdering the boy. He told the investigators that he had killed Andrei and drained his blood using “special ritual implements.”

Beilis was indicted in January 1912 and his show trial began in May of that year. The very fact that Beilis had been put on trial resonated across the globe because it was clear to everyone that the charges were false – and that for all intents and purposes, it was a blood libel. Protests broke out in Germany, English clergymen published an open letter on the matter, and intellectuals and people involved in the arts demanded that the trial be canceled without delay.

Alexander Tager, an attorney, wrote: “The entire country was up in arms over the trial. The Bolshevik underground, the liberals and the centrist factions. There were also threats of a general strike. But the extreme right continued to fuel the blood libel.”

The following was written in a local newspaper in Kiev on October 12, 1913: “As expected, everyone realizes that Beilis has no connection to this. It is a fabricated, formal trial. The trial has been in session for many, many days and Beilis’s name has not even been mentioned.”

The best attorneys in the Russian Empire took upon themselves to defend Beilis, headed by Israel (Oskar) Gruzenberg (yes, the same Gruzenberg who has streets named after him in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem). In addition to being one of the most prominent Jewish lawyers in Russia, he also specialized in handling criminal cases that were motivated by antisemitism.

Even though he was born in the Pale of Settlement, Gruzenberg managed to get accepted to the Faculty of Law at the University of Kiev and graduated cum laude. The university’s administration offered him a position on the teaching staff, but under one condition: that he convert to Christianity. Gruzenberg refused, and as he himself later said, he never regretted that decision. “Instead of being engaged in research, I preferred to fight in the courts.”

His first big case also had to do with a blood libel, after a Jewish pharmacist named Blondes from Vilna was accused of trying to murder his neighbor. Just like the Beilis case several years later, the neighbor accused Blondes of assaulting and draining blood from her. Attorney Gruzenberg identified an opportunity to turn that case into a precedential one and offered to represent the defendant. The court found Blondes guilty as charged, but Gruzenberg, together with two other lawyers, filed an appeal and Blondes was acquitted.

“You can believe me or not, but if knew or thought, even for a moment, that the Jewish religion permits the use of human blood, I would not agree to remain a Jew.” That is what Gruzenberg said in his six-hour opening statement for the defense at Beilis’s trial. During his statement, he made arguments against all the trumped-up charges and presented his own evidence that proved the defendant’s innocence. The court had no choice but to acquit Beilis.

The Beilis trial became the most famous show trial in the Russian Empire in the pre-revolutionary period. On October 28th, a year after the trial started and more than two years following his arrest, Mendel Beilis was released. Thousands of people gathered near his home to congratulate him because the truth had finally come to light.

A few days after the acquittal, a sign was installed at the public transport stop next to Beilis’s home, on which the words “Beilis Station” were written. The sign was put up for the benefit of the numerous visitors who came there and wanted to meet him in person. On the other hand, due to the threats on his life, the district governor demanded that Beilis leave Kiev. At the end of 1913, the Beilis family took a train to the port city of Trieste in Italy, and from there traveled by ship to Alexandria in Egypt. In January 1914, they arrived in Jaffa Port, where huge crowds were waiting to cheer Beilis all along the route to Herzliya Hotel in Tel Aviv.

In 1921, after encountering financial problems and learning that his eldest son had committed suicide, Beilis left for the United States. His family later joined him in New York. Beilis recounted the story of his incarceration in a local newspaper, and in 1926 published a memoir in Yiddish and English, entitled The Story of My Sufferings. The book was first translated into Russian only in 2005.

After his sudden death in 1934, Mendel Beilis was buried in a cemetery in Queens, New York. His gravestone bears the following inscription:

Make note of this grave

Here lies a holy person, a chosen man.

The people of Kiev made him a target

And imposed the suffering on all Jews.

They falsely accused him and his community

Of taking the blood of a Christian child to observe

A fabricated tenet of his faith on the Passover festival.

They bound him in chains and lowered him into a hole

And for many years he did not see the light of day.

And to punish all Jews he was brutally tortured.

Pay tribute to this pure and innocent soul

Who dwells in the shadow of the Lord in the heights of heaven

Until those who sleep shall awaken to life.