Hiroo Onoda was a high-rank intelligence officer in the Japanese army. Sent during World War II to the Lubang island in the Philippines, his orders were to do literally everything to prevent the enemy from invading the island. Should he failed, he’d better not return to Japan, they said. Hiroo Onoda had no intentions to defy his superiors, therefore after an American force did invade the island, on February 28, 1945, and surrendered the Japanese, he took off to hide in the woods. He lived there for years, with nothing but his sword, stems and stolen rice to feed on, and restless passion to fight back the Yankee enemy.

Some 30 years after he was assigned, in February 1974, Onoda met a young Japanese man called Norio Suzuki, who told him the whole truth: the war has ended way back, the Nazis were defeated, and in his homeland, they even had the time to invent a new technology called Video. But Hirro persisted and would not let go of the illusion that gave his life meaning. Only after Suzuki sent a new order from Japan, allowing him to leave his hiding place, the obedient officer returned to Japan, where he was welcomed and praised as a national hero.

If this crazy story of an extreme devotion sounds unusual to you, simply replace the Americans with bishops, the World War with the terror of the Inquisition, and Lubang with Belmonte, Portugal – and there you have it: the story of a unique Jewish community, forced by tragic circumstances to live in false realization for centuries.

In 1496, four years after the expulsion from Spain, Manuel I King of Portugal wished to marry the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, king and queen of Spain. Some parents expect the obvious petty things from their future son in law: to support their daughter, to be a loyal husband and a devoted father. Not Ferdinand and Isabella, though. Their only condition was: if you wish to marry our daughter, you must deport all the Jews from Portugal, like we expelled them from Spain. Parents can be like that, you know.

The expulsion decree for all the Jews of Portugal was issued on December 5, 1496. A few months later, Manuel I noticed that the Jews’ departure caused his kingdom’s GNI to drop, so he panicked and revised the decree: Jews shall not be deported, but rather shall be forcefully and misleadingly converted to Christianity. During April 1496 Jews were brought to central squares, having been told that ships were waiting to take them out of the country, but instead, they were forced to undergo a conversion ceremony. The sights were horrifying. Those who refused were dragged brutally, and if they insisted they were sent to the auto-da-fé ritual, where they were burnt at the stakes.

Belmonte is a village close to the Spanish-Portuguese border, with some 3,000 residents. The village’s stone houses are joint together in a labyrinth of narrow alleys with beautiful squares between them. In 1496 there were 200 Jews living in Belmonte, who suffered the same fate as their fellow Jews across Portugal, and had no choice but to convert.

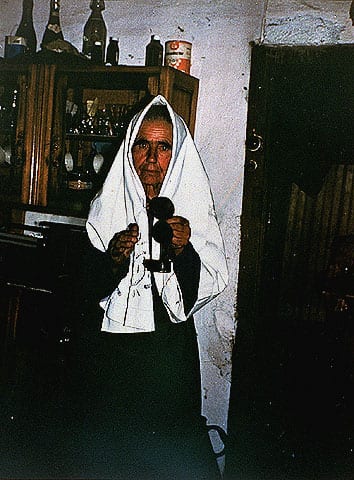

Though the Jews of Belmonte had no intention of breaking the holy covenant between God and the children of Israel, they certainly did not wish to die either. And so, like many other Jews in Portugal, they made the difficult choice: to be Jews indoors, and Catholic outside. There are plenty of stories about the double life they had to lead: how they celebrated Christmas, baptized their children and attended the mass in church, and then at nights they used to cover their heads, light candles, fast on their fasting days, and make Challot – literally risking their lives with each of these actions.

What was special about the community of Belmonte was that being a secluded community, they were absolutely sure that they were the last Jews remained. For over 400 years they led this double life, firmly convinced that the inquisition was still lurking outside, and picturing that the entire Jewish nation was wiped out.

Is it good news or bad news? Depends on your point of view. For Anti-Semites, knowing that there were only 200 Jews remained in the entire world was wonderful news. But the Jews of Belmonte, on the other hand, it was a heavy responsibility as much as it was great pride. As the sign at the entrance to the community’s new synagogues states: “Here in the village of Belmonte the candle has not burnt out, here in our houses the Jewish rituals were secretly held for 500 years. Here the Jewish soul was never diminished, it prevailed for eternity.”

The Jews of Belmonte used sophisticated ways to maintain their tradition. They baked Matsot in the basements, prayed in Yom Kippur were hidden as cards games, they lit Shabbat candles as if they were practicing the Candlemas ritual, and built the Sukah indoors. They did not circumcise the children, because it was too dangerous to have them walk around with such an incriminating sign, and carried little wooden mezuzas in their clothes instead of fixing it unto their doorposts.

Just like in the case of officer Hiroo Onoda, the misconception of the Jews of Belmonte had to come to an end someday. It happened in 1917, 420 years after the inquisition decree. A Jewish mines engineer from Poland called Shmuel Schwartz came to town and declared himself a Jew without a shred of hesitation. Caught up so deeply in their centuries-old illusion,

the Jews of Belmonte put Schwartz into a test. One of the elder women, of the village’s leadership, argued: since you have pretensions to know Jewish prayers that are different from ours, please let us hear at least one, in that language you call Hebrew, which you say is the language of the Jews. Schwartz agreed and recited “Shema Israel” to the public of his listeners. When he said the name of God in Hebrew, all villagers were moved and convinced he was indeed a Jew.

Years have passed, and like many other Jewish communities around the world, the community in Belmonte too diminished. Today, less than ten Jewish families are living in Belmonte, still hoping deep in heart that their descendants will carry on and hold on to their ancient faith, freely, proudly, and publicly.