The possibility of imitating winged creatures has always sparked the French imagination. The Montgolfier brothers were the first to fly a human-carrying hot air balloon, and Louis Blériot was the first inventor-adventurer to complete an international flight – from France to Britain in July 1909.

Several months after Blériot crossed the La Manche (English) Channel, a 17-year old Jewish boy crossed Montien Boulevarde toward the Eiffel Tower, when a wondrous and life-changing specter burst through the clouds. A strange winged contraption flew lightly and elegantly over the boy’s head, bearing a grinning Count Charles de Lambert, a pioneer of French aviation and student of Wright Brother Orwell.

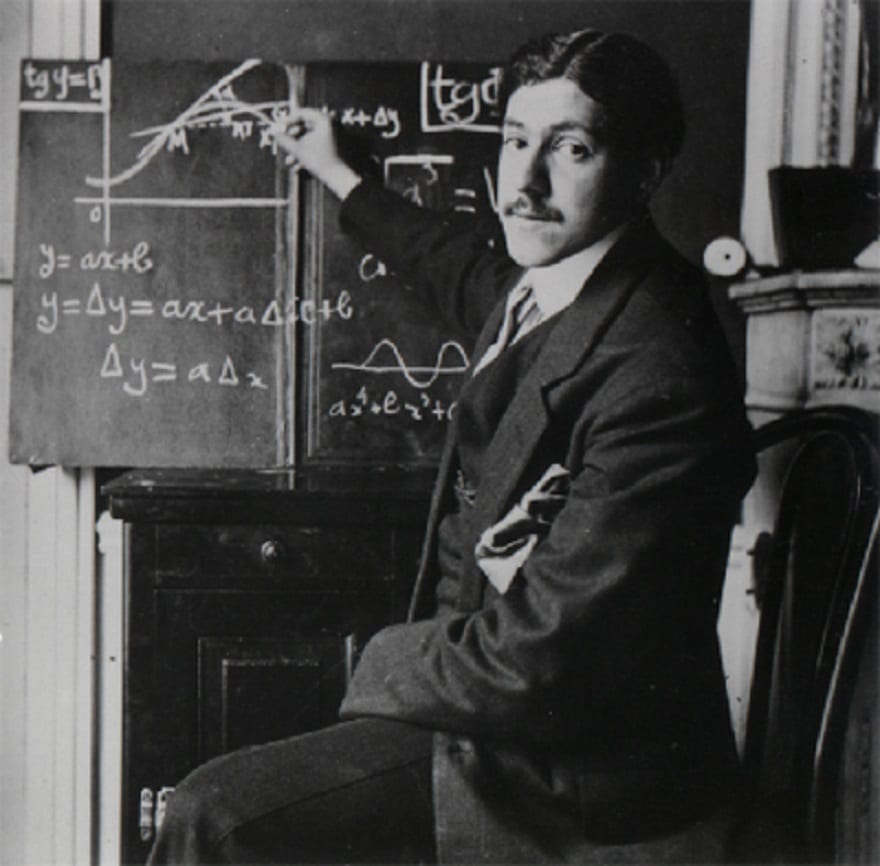

The boy, Marcel Bloch Dassault, would one day say that the moment he saw Count Lambert fly over the Eiffel Tower, he decided to join the prestigious club of French engineer-inventors. He did not yet know that his decision would influence a tiny nation that would be established in the Middle East 40 years later.

Young Bloch’s decision evolved from idea to action and immediately after he graduated from high school, he applied to the high college of aeronautics, France’s first school of aviation – from which he graduated in 1913.

How talented an engineer was he? He is still mentioned with Kelly Johnson and Artem Mikoyan as one of the three founding fathers of aeronautics. At 22, Bloch invented an airplane propeller that was so successful that France dismantled the propellers in its fighter planes and replaced them with Bloch’s propeller. France’s top flying ace Georges Guynemer, who sent 57 enemy planes to their final reward, said at the time he would not have been able to down so many planes had it not been for Bloch’s propeller.

In 1931, Bloch established the eponymous Marcel Bloch plane company, identified by his initials, MB. During that period, the Jewish engineer dreamed up airplanes of all types: the innovative MB-220 passenger plane, the triple-engine, ten-seat MB-120 cargo plane, and the MB-210 bomber, that reached a cruising altitude of 32,840 feet – when no other bomber could fly beyond 30,000 feet.

The quality of the planes produced by Bloch and his then-partner Henry Potez was such that the company’s headquarters in a giant hangar in Bologne was flooded with orders for planes. The two men thus quickly established other factories throughout France. This financial success was nipped in the bud in 1936, when the socialist Popular Front party rose to power. The party did not view fondly capitalist ventures that turned ingenuity and talent into money – it nationalized Bloch’s company.

To the sorrow of zealous defenders of equality, God did not hand out talent equally. And because French aviation minister Pierre Cot was lacking any talent with which to lead the largest industrial aviation firm in France, Bloch was named managing director of the company which had just been seized from his hands. Despite the lack of personal profit during that period, Bloch’s fiery mind did not cease to concoct and produce the MB-150 fighter plane and MB-170 bomber series.

But that was all too little too late. In June 1940, the French personally paid the price of their demonstratively soft-on-Nazi-Germany policy. The land of the tricolor flag was conquered and bisected – the North in German domain and the South controlled by the puppet Vichy government.

The S.S. carried out orders, and their orders explicitly demanded that Jews be exploited to their limits before their extermination. The Nazis considered Bloch to be a useful individual, a wellspring of knowledge and genius whose value was greater than gold. To their surprise, when they asked him to share his knowledge with them – thus saving his own life and that of his family – the Jewish engineer adamantly refused to collaborate.

At first, he was jailed with his wife and son in the infamous Fort Montluc prison. Later, he was sent to the Drancy concentration camp in Paris, considered to be among the cruelest concentration camps, and finally he was sent to Buchenwald to “live” out the war. In the camps, he decided to add the name “Dassault” to the Bloch surname. “Dassault” – meaning, “for battle,” – was the nom de guerre that his brother, General Darius Paul Bloch, used in the French underground. Darius Bloch, a national hero, is worthy of his own article.

Despite partial physical paralysis, Marcel Dassault’s spirit did not flag. Immediately after the war, he tackled the company’s rehabilitation with renewed strength. It quickly became a world leader in the fighter plane and jets field. The “Oregon,” “Mystere,” “Super Mystere,” and of course the “Mirage” Rolls-Royce of aircraft earned Marcel Bloch a place in the pantheon of the greatest engineers in history.

During the years of its operation, the Daussault aviation company produced more than 8,000 planes, including the 50 that star in a special story. In 1967, French President Charles de Gaulle imposed an embargo on Israel. The Israel Air Force had already signed a contract with the Dassault company to purchase 50 upgraded Mirage 5s.

Angered by the decision, the Israelis did not give in. Less than a year later, a carton of documents landed in Mossad headquarters, including the full plans for producing a Mirage 5. The man who passed along this golden intel was an enlisted Mossad agent, a Swiss engineer named “Alfred.” The more than 200,000 documents transferred by Alfred Frauenknecht were used to develop the Israeli Nesher aircraft, the harbinger of Israeli manufacturing of additional planes like the Kfir which put Israel on the map of aircraft production.