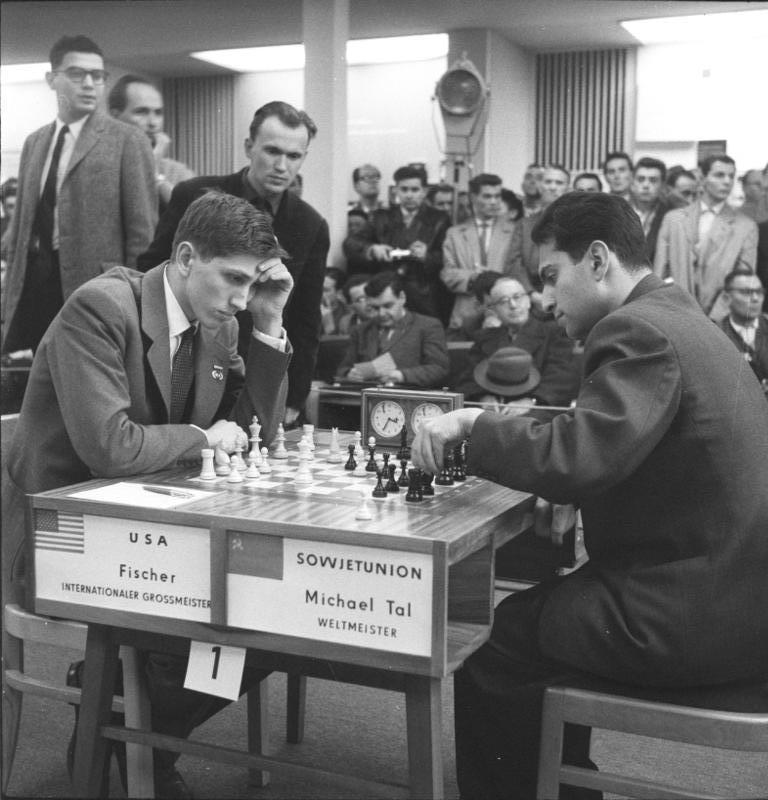

He was paranoid, provocative, racist and chauvinist. But most people forgave him all of it, because he was a singular genius with an IQ over 200 and the memory of a Google server farm. Bobby Fischer, World Chess Champion from 1972-1975, harbored neuroses that spilled over into his personal and public lives. As a teen, he joined a Christian cult called the Worldwide Church of God, which believed that the apocalypse was imminent. He also developed a hobby then that would become central in his life after retirement: intense anti-Semitic activity.

The brilliant chess master began at some point to check the pieces on the board before every match, lest they were made from toxic material. One explanation for his troubled soul was the lack of a male figure during his childhood. Bobby’s biological father, Paul Nemenyi, was a Jewish physicist who emigrated to the US from Germany and had an affair with Bobby’s mother, Regina. People who knew his father said that the resemblance between father and son went beyond their identical facial features – they shared the peculiar behavior typically ascribed to disturbed geniuses. Paul was said to carry soap in his pockets with which to wash his hands after touching door handles and to wear pajamas under clothes made from animal materials.

It was ironic – to say the least – that the son of a German refugee expelled from his university position because of his Jewish heritage, became in his youth a Holocaust denier and avid Jew-hater. Was Fischer’s loathing of Jews vengeance for the revelation that not only his mother – but the father who abandoned him – were Jews? That is a question for psychologists. The bottom line was clear: Fischer abhorred Jews. He first uttered thuggish anti-Semitic comments in the 60s, saying: “Jews were always lying bastards throughout their history”; and “There are too many Jews in chess.”

In the latter statement, he – at least – got Jews’ relative numbers right. Chess is considered an unabashedly Jewish game. To commemorate the 11th anniversary of the mad genius’s death (17.1.2008), let’s address the connection between Jews and chess, the game of kings.

Like literature, art and science, chess exemplified the 19th-century Jewish renaissance. The first Jewish Worldwide Chess Champion was Wilhelm Steinitz (an ancestor of Israeli Minister Yuval Steinitz). Wilehelm Steinitz, born in Prague in 1836, was the son of a haberdasher who wished a rabbinic career for his son. He soon realized that his young jewel had exceptional math skills and enrolled him in the Vienna Technion. That was where Steinitz discovered chess. And the rest is history.

When Steinitz decided to make chess his life’s work, he moved to London, where in 1866 he became the first undisputed World Chess Champion. Blessed not only with exceptional brains – but with extremely short stature, a sharp tongue and a violent temperament – Steinitz soon bumped heads with the British chess community and migrated to the US. One of Steinitz’s major contributions to the game was a strategic “defensive position,” a solidly defensive placement of the pieces from which to launch surprising and brilliant attacks, that unnerved his opponents. Lacking ability to wisely support himself despite the handsome winnings from his matches, he died impoverished in a New York public hospital.

Steinitz’s loss of the World Chess Championship to another Jew, Emanuel Lasker, bore witness to the extent to which chess was “a Jewish profession.” Lasker was born in Prussia to a family of famous cantors. Jews in other European nations also took complete control of the game. The first Polish champion was Dawid Przepiórka. The first German champion was Berthold Englisch. The first French champion was Samuel Rosenthal. The first US champion was Samuel Lipschutz. And the first Romanian champion was Alexandru Tyroler. All Jews. There were two Jews, Lasker and Siegbert Tarrasch, among the first Chess Masters granted that title by the Russian Tsar in 1914.

Just as Jewish boxers Salamo Arouch and Victor Perez used their talent to survive the Holocaust, chess helped Jews escape death. The most famous story is that of Ossip Bernstein, born and raised in Ukraine, who became a renowned chess player. Bernstein fled Russia for France during the civil war and was arrested in Odessa by the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police, and put before a firing squad. As the firing squad was taking its positions, their commander asked to see the names of those to be executed. When he saw Bernstein’s name on the list, he asked if he was the famous chess player. When Bernstein confirmed his identity, the commander ordered that the prisoner play a game against him. The agreement was that if Bernstein lost or tied, he would be killed. Of course, Bernstein won and before he had the opportunity to meet another lesser Bolshevik officer and amateur chess player, Bernstein escaped on a British ship and settled in Paris.

As silly as it sounds, the connection between Jews and chess became fodder for the Nazi propaganda machine, which claimed that phenomenal Jewish success in the game of kings was evidence of Jews’ twisted and unproductive characters. To illustrate their baseless theories, the Nazis enlisted the then-world champion, Alexander Alekhine, to publish – as if under his name – six anti-Semitic articles, slamming Jewish players and their influence on the world of chess. These articles portrayed prominent Jewish chess players as decadent and gutless players, who relied mainly on defense. Not coincidentally, the authors of Alekhine’s Nazi articles “forgot” to include the name of the most famous Jewish chess player of that time, Rudolf Spielmann, a daring and aggressive chess master for whom sacrificing pieces was a central strategy.