Once upon a time there was a man – says the Talmud – whose wife died in labor. The man was so poor that he didn’t have the money to hire a wet nurse for the new baby. And then a miracle happened. According to the Talmud, the man grew breasts bursting with milk. Rabbi Yosef said: How great is the man for whom this miracle was performed. Rabbi Abaye replied: Moreover, how terrible is the man for whom the natural order of Genesis was transformed.

The story in Talmud Shabbat 53b presents two approaches in Jewish thought to the concept of miracles. The first views a miracle as confirmation of the reality of a divine power capable of reordering things, intervening in the laws of nature, and bending reality according to will. The second approach believes that heavenly wisdom is embodied in the laws of nature themselves. That approach maintains that what makes an event a miracle is in the eye of the beholder. He may willingly choose to interpret it as an arbitrary and meaningless coincidence. And he may willingly choose to experience it as part of a plan expressed in a number of stories by an all-knowing storyteller, who intentionally planted the event in space and time. As Albert Einstein famously said: “Coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous.”

Leading representatives of these opposing approaches to the meaning of a miracle existed in Jewish thought. Among the renowned supporters of blatant divine intervention in the laws of nature were the Ramban and Rabbi Yosef of the aforementioned Talmud story. The Amora Abaye and the great Ramban were the dominant proponents of the principle that God’s will is embodied in the laws of nature. The Rambam maintained that events perceived as miracles derive from a divine plan sourced in the Creation – that they do not actually depart from the laws of nature. That is to say that miracles are part of the natural reality, and that what makes them miracles is our belief that they are.

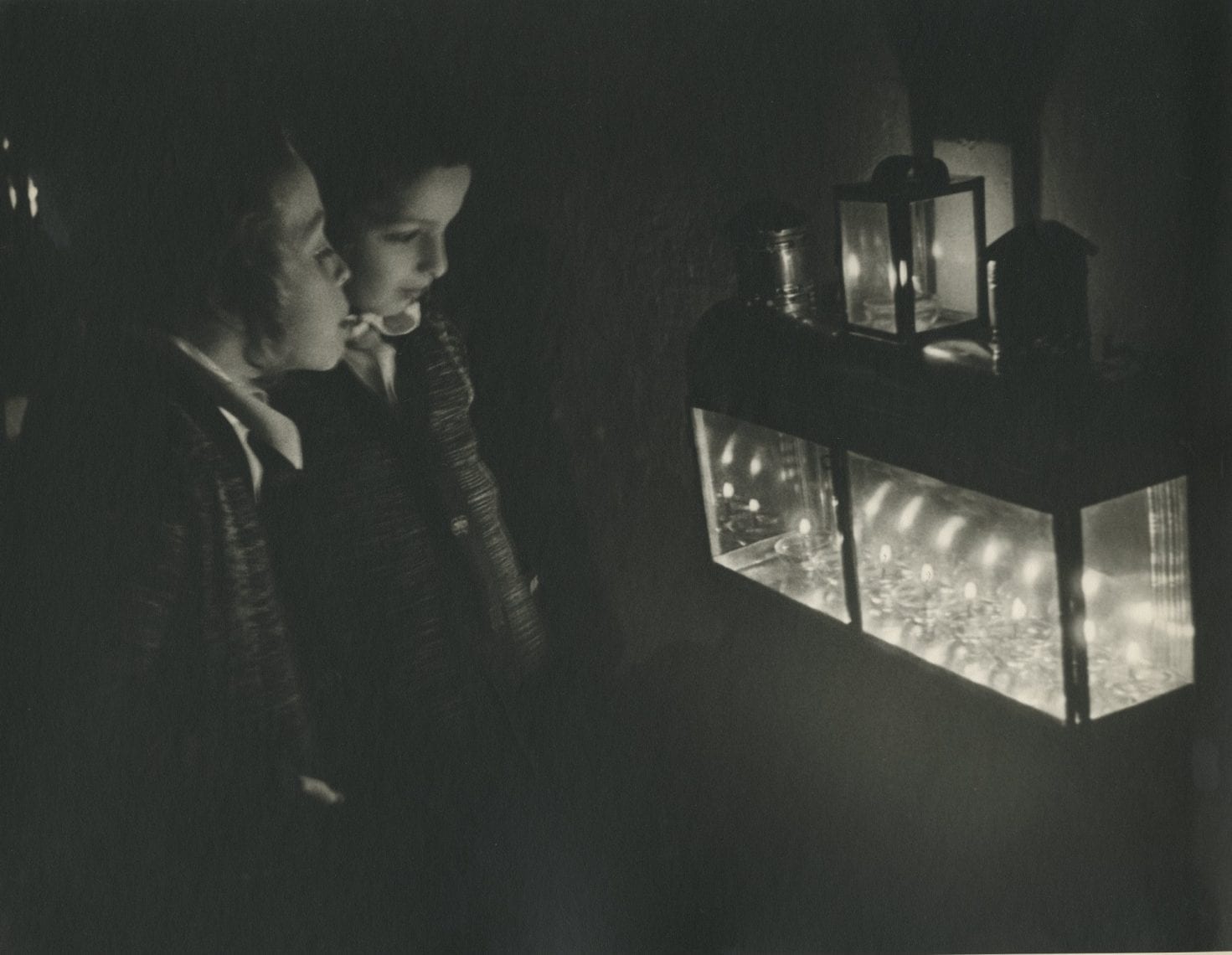

The Hannukah story provides a fascinating glimpse of shifts in the approach to miracles the throughout generations. The story actually contains two miracles. One miracle is that of the cruse of oil that lasted eight days; and the other is the glorious victory of the Maccabees over the Seleucids.

In their capacity as the Jewish diaspora’s then-ministers of education and culture, the sages determined that the main focus of the story was the miracle of the cruse of oil. A miracle that comprises a change in the laws of nature themselves, and proof of God’s external intervention in natural reality. These sages’ focus was motivated by their wish to instill hope in an anguished and dispersed diaspora. Placing the cruse of oil at the center of holiday ritual evoked the Shepherd telling his flock that miracles could happen – that despite their seemingly dark and desperate external reality, God had not abandoned them.

When the Jewish People returned to its Land, the Zionist leaders returned the miracle of the Maccabees’ victory to the center of Hannukah. Because the Maccabees’ victory against the Greeks belongs to the second definition of the miracle – that is, it does not necessitate a shift in the laws of nature – we returned to a subjective view of the miracle.

One can see the Maccabean victory from both perspectives. From the atheist perspective viewing the Maccabean victory as the outcome of coinciding events, in which confluence arbitrarily led to victory; or from the religious perspective which ascribes the victory to the intentional hand of God. As is written in the Al HaNissim prayer that we read in synagogue on Hannukah.

“You in Your great mercy, stood up for them in their time of trouble…You took their revenge; You delivered the mighty into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of the few.”

There were voices in the Zionist Movement reflecting both sides. The rebellious pioneers of the Second and Third Aliyot associated the Maccabean victory with the rise of the Jewish People – they strove to expropriate the miracle from the Divine and transfer it to man. In their minds, this was neither miracle nor divine plan, but the effective act of flesh-and-blood people. This approach is expressed in the well-known Hannukah song “Anu Nosim Lapidim,” written in 1930:

“No miracle befell us… We quarried rock until we bled – And then there was light!”

In contrast, there were voices in the Zionist Movement who viewed the Maccabean victory as they did the return of the Jewish people to its Land: The outcome of a divine plan, the Dawn of Redemption and cosmic miracle that returned the Jews to history.

At his seminal commencement speech at Kenyon College author David Foster Wallace told the following story: “Two guys are sitting in a bar in the remote Alaskan wilderness. One of the guys is religious, the other is an atheist, and the two are arguing about the existence of God with that special intensity that comes after the fourth beer. And the atheist says: ‘Look, it’s not like I don’t have actual reasons for not believing in God. It’s not like I haven’t ever experimented with the whole God and prayer thing. Just last month I got caught away from the camp in that terrible blizzard, and I was totally lost and I couldn’t see a thing, and it was fifty below, and so I tried it: I fell to my knees in the snow and cried out ‘Oh, God, if there is a God, I’m lost in this blizzard, and I’m gonna die if you don’t help me.’ And now, in the bar, the religious guy looks at the atheist all puzzled. ‘Well then you must believe me now,’ he says, ‘After all, here you are alive.’ The atheist rolls his eyes. ‘No, man, all that was was a couple of Eskimos happened to come wandering by and showed me the way back to camp.’”

Wallace’s anecdote is the whole story in a nutshell. The same exact experience can have completely different meanings for two different people. It depends on those people’s differing patterns of belief, and the different ways in which they construct meaning from experience. Which of these guys was right? The atheist who saw his rescue as a chain of random and meaningless incidents, or the religious guy who believed that the two Eskimos were cued by a supreme producer conducting human drama. The beauty – or in this case, the miracle – is that it is completely in the eye of the beholder.

Happy Holiday!

(Translated by Varda Spiegel)