A quote that religious Jews in Israel enjoy hurling in heated arguments with secular Jews is that of the founder of the Hashomer Hatzair Movement and spiritual leader of the kibbutz movement, MK Yaakov Hazan: “We wanted to raise a generation of apikorsim [non-observant Jews], but instead raised a generation of amei haaretz [unlearned Jews].”

This quote is one in a collection of religious hubris, which includes “the parable of the empty wagons” from the famous discussion between Ben-Gurion and the Hazon Ish; and Reserve Major General Yaakov Amidror’s, “Secular Jews are Hebrew-speaking Gentiles.” It reflects both the desire to diminish those who typically argue for secular Judaism, and to debate those learned secular adversaries, who study Gemara on Shabbat while smoking a cigarette.

This is a good point of departure from which to examine what history teaches about heretic Jews, and mainly to clarify how the religious Jewish community accepted the first heretics, who arrived on their doorstep early in the Modern Era.

Uriel da Costa was born c. 1590 to a wealthy distinguished family in Porto (the city after which Portugal was named). Given the name Gabriel by his Catholic father and Jewish mother, he knew nothing of his Jewish ancestry until adulthood, and lived the typical life of noble young Catholic men in Porto.

At the age of 20, he held the respected position of treasurer of the church. After his father’s death, da Costa delved into theological issues and started to read the Old Testament. The Book of Books was not standard reading material for a young man of his class – it turned his world upside down. He also discovered at that point that his mother was Jewish and decided that he wished to become a Jew. But the terrors of the Spanish inquisition in Portugal held him back from doing so. Historians estimate that from 1618-1625, 143 residents of Porto were accused by the Inquisition of practicing Judaism and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

At the age of 22, da Costa fled Portugal for Amsterdam, the most tolerant, free city at the time.

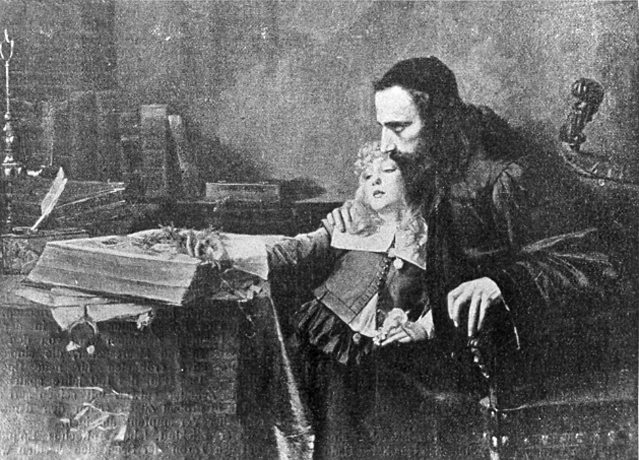

Before he arrived, he circumcised himself and changed his name to the Hebrew “Uriel”. Having come completely out of the Catholic closet, he thought he would be able to live as a free Jew. But he would soon be very disappointed. Sadly, the young intellectual discovered that the Judaism he had studied in Porto was nothing like the Judaism he encountered in Amsterdam – the largest Jewish community in the world at the time. That Judaism rested on strict rabbinic Halacha that obligated its tens of thousands of followers to observe rules and regulations, which da Costa searched for repeatedly but could not find in the Biblical text. He perceived this as a Jewish version of the Catholic religion that he had abandoned – not the Biblical “religion of reason,” that captured his heart when he read the Torah portions by the dim light of a candle in his attic in Porto.

Angry and bitter, he sat down to write a harsh indictment of the rabbinical establishment, entitled, “Objections Against Tradition.” When asked to denounce this document, he refused. In response, the Jewish community excommunicated him and burned the text. There was nothing for an excommunicated Jew to do in those days except await death by starvation. It was forbidden to hire, host, or offer an exile food or shelter. The only way to escape this insufferable double-exile was conversion to Christianity. Da Costa decided to forgo the pleasure. Given his biography, a return to the religion of his youth would be more than terrifying.

He lived in solitude and misery for many long years. Children threw stones at him as he walked down the street and adults pointed at him as if he was a freakish monster. When he could no longer endure the humiliation, he decided to repent – in word only. He started to live a secret life: Believer by day and heretic by night. Ironically, most of the Jews of Amsterdam were descendants of Anusim, who were exiled from Spain and Portugal. In practice, da Costa was an Anus among former Anusim. In the autobiography that he wrote late in life, “Exemplar Humanae Vitae,” da Costa defined his repentance as a conscious decision to live “as a monkey amongst monkeys.” This was not exactly a description of a man who had repented with all his heart.

His ability to persuade himself also had a limit – da Costa simply failed to hold his tongue. In time, his opinions became extreme and he adopted a naturalistic world view, which maintained that God and the laws of nature were one and that man had invented all religions.

His temperamental nature finally won out. The contradiction between his self-knowledge and his public lifestyle led to another grievous conflict with the community, which ended again in excommunication. After a long period of banishment, Da Costa succumbed to the terrible loneliness and begged the community again for forgiveness.

This time, the community leaders choreographed an exceptionally cruel humiliation. In a ceremony in the Great Synagogue of Amsterdam, da Costa was first forced to confess his sins, then endure 39 lashes, and finally to lie on the threshold and let the entire crowd step over his body. Just as the Church had tortured them and their ancestors during the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisition, they tortured their heretic brother in Amsterdam.

Da Costa never recovered from that humiliating ceremony. He grabbed a pistol a few months later and shot himself in the head in the middle of the street. An eight-year old boy was playing with his friends, at the time, in a nearby yard. The boy, Baruch Spinoza, did not know that the wretched man who committed suicide several streets away had paved his path to becoming “the first secular heretic in history.” They isolated and exiled Spinoza as well. But unlike da Costa, Spinoza was not broken. He proved to the Amsterdam Jewish community that no matter how hard they tried to make him out to be an am haaretz (an unlearned Jew) – some people are simply born apikorsim (non-observant Jews).