Last year, Claudia De Benedetti was launching her book in a ceremony held in Casale Monferrato in Piemonte district, Italy. Her book is a fascinating research on the history of her family, one of the renowned aristocratic families in Italy. While delivering her moving speech, she still did not imagine that the real thrill was yet to come. As the event was almost over, a woman in her sixties came upon her and said, my name is Sandra, and I am named after your aunt. After a short pause, she uttered the final jaw-dropper: In fact, I am Pietro Bo’s daughter.

When Claudia was able to speak again, the two women went out to talk in a nearby restaurant, next to the great synagogue in Casale Monferrato, considered one of the most beautiful synagogues in Europe. Soon enough they were reminiscing about the old Fiat 500 Topolino 37, that shall forever bond together the De Benedetti and the Bo families.

The De Benedetti family is an Italian Jewish elite. Their branched family tree reaches the 1492 expulsion of the Jews from Spain and includes Edgardo Mortara, the Jewish boy whose scandalous abduction by Catholic authorities in 1858 resulted in the foundation of the Alliance educational network. Another famous branch includes the Donati family from Modena, from which many famous bankers, jurists, diplomats, and industrialists were descended. Claudia’s great grandmother’s brother, for example, was Angelo Donati, a Jewish Italian diplomat, and philanthropist who used his fortune and connections among Italy’s high officials to save thousands of French Jews during the Holocaust, while serving as the ambassador of San Marino. Claudia De Benedetti is a businessperson, curator, author, philanthropist, and a member of the Maccabi World Union board of directors, as well as the international board of governors of the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

The following events occurred during the Second World War, in the magnificent Piemonte district in northern Italy. Naturally, wartimes have their typical absurdities, and in the first years of the war, Jews who held Fascist Italy’s i.d’s, were also the lucky ones, who were holding the keys for survival and liberation. This was also the case of the De Benedettis from Turin.

The family owed their prosperity, based on banking, industry, and finances, to the Italian king Carlo Alberto, who in 1848 granted full emancipation to the Jews, after centuries of repression and discrimination. Up until then, the Jews of Turin were not allowed to purchase buildings, join the army or leave the quarter during Christian holidays and processions. For a long time, they were forced to wear a yellow badge and could not study in state official schools and universities.

In an act of gratitude, wishing to adorn their city, the Jews of Turin, including the De Benedettis, initiated the erection of the Mole Antonelliana, a celebrated synagogue designed to seat 1,500 worshippers, in the center of town. Today, the pointed building is Turin’s most recognizable landmark. The construction lasted for four decades, due to technical issues resulting from the problematic proportions between the narrow base and the overall height and weight of the structure. Turin Jews had a love-hate relationship with the synagogue, as it represented for them their own situation: based on a national extremely narrow basis. Eventually, perhaps fearing an evil eye, they decided to give the building up and transfer ownership to the municipality in 1877.

Half a century later, all their concerns and fears came true. The fall of the fascist regime in Italy on July 25 1943, followed by the surrender to the allies, resulted in Nazi Germany’s invasion. Italy was divided in two, the north was taken by the Germans while the allies held the rest of the territories. Dangerously, the De Benedettis and all the Jews of Turin, remained in the unfortunate area.

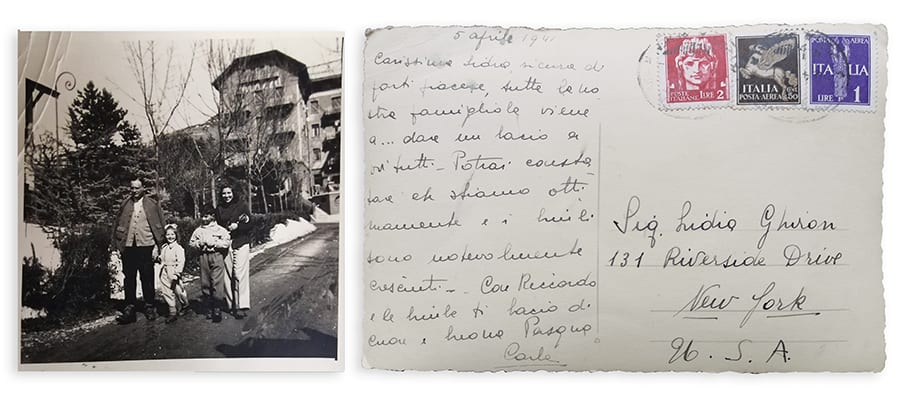

“I was just a kid when my grandma Carla told me about our family’s whereabouts in the Holocaust for the first time”, said Claudia, unfolding the events following the Nazi’s invasion to north Italy. “Rumors about the transports to unknown destinations that never came back reached my grandpa, Giulio De Benedetti. Giulio and Carla did not think twice, they packed and took my father, Camillo, his sister Sandra and their old parents, hasting to leave Turin to a small village called Stevani.

While in the village, the De Benedetti family developed close friendship with their neighbors, a poor family of farmers – the Bo family. Quite often at times of war, class differences disappear, especially when it comes to children. “They were inseparable; you could not find one without the other. My father Camillo, his sister Sandra and the Bo children: Renzo, Ottavio, Pietro, and Corinna.

A few months after the occupation of the north, even the village house became unsafe. Grandpa Giulio realized that had to move on and the family planned to cross the border to Switzerland for a safe haven. The parents were somewhat perplexed, as they owned many pieces of jewelry, diamonds, valuable art items and lots of money, which they knew they could not take with them.

Then the children came up with a brilliant idea. They suggested to put all the valuables inside their small Fiat 500 Topolino 37, that Giulio brought from Turin, and burry the whole car in a large pit. The kids dug the hole in the Bo family’s yard and drove the car inside. When they were done they covered up the entire area, and the Topolino was completely out of sight.

Two years later, on July 13 1945, after the end of the war, the De Benedetti family returned to Stevani, for an emotional tearful reunion with the Bo family. Renzo and Corrina once again shoveled the yard, slowly revealing that old Fiat 500, still holding all the family’s precious belongings. Nothing was damaged, nothing was missing.

Though the Bo’s had a treasure just two feet from their living room, that could change their lives; and even though they must have heard about the homicide of the Jews of Europe and knew they had a reasonable excuse for taking the treasure for themselves – they chose to keep it all safe until their neighbors and friends shall return.

This is just one story out of countless similar chronicles. On this upcoming International Holocaust Day, it is crucial to remember the great many non-Jewish good-doers, who risked their lives attempting to rescue Jews, thus beautifully executing the old Jewish command: “In a place where there are no men, strive to be a man” (Pirke Avit 2).

(Translated from Hebrew by Danna Paz Prins)