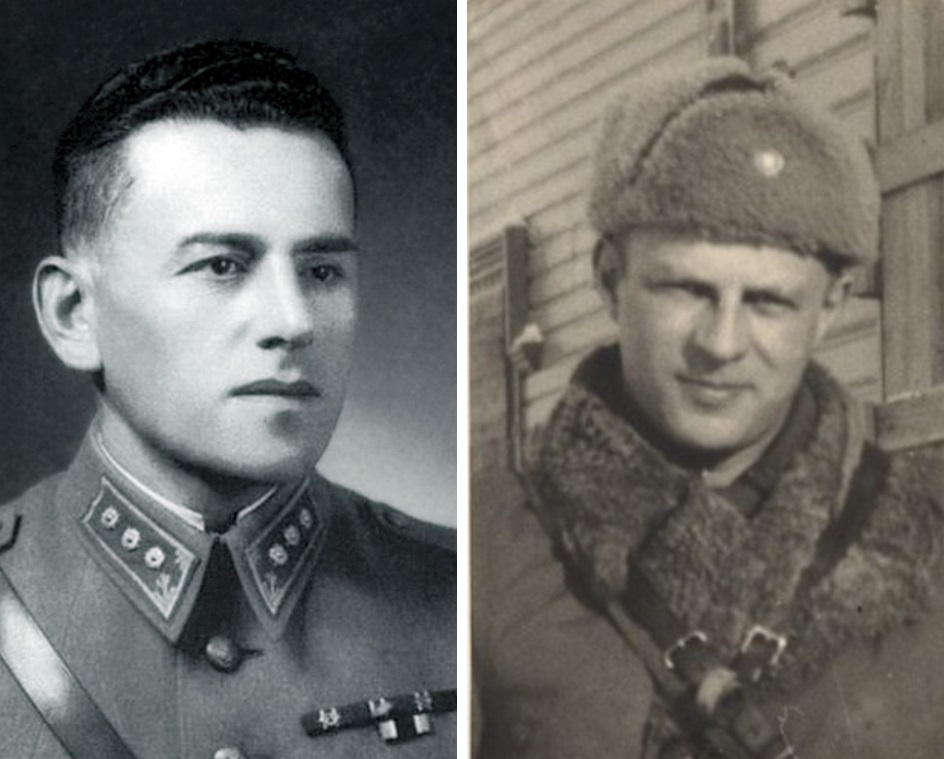

“Tell them in these words: I am a Jew and I refuse.” That is what Captain Leo Skurnik said when he learned that the Germans had recommended that he receive an Iron Cross medal for his heroism on the battlefield. Skurnik, a medical officer in the Finnish army, organized the evacuation of a field hospital under heavy Russian shelling, saving the lives of around 600 Wehrmacht soldiers. When the Germans wanted to punish him for his rebuff, Skurnik’s commander, General Hjalmar Siilasvuo, told them: “You don’t really expect that I’ll hand over my best doctor?”

Skurnik was not the only Jew who found himself fighting alongside the Germans. As much as Finnish Jews hated the Germans before the outbreak of World War II, that hate paled in comparison with their animosity towards and historical fear of their Russian neighbors. And they had good reason, surely until they learned about the horrors of the Holocaust of European Jewry perpetrated by the Nazis.

In 1939, there were approximately 2,000 Jews in Finland. Most of their families were originally from Eastern Europe, who had emigrated to Finland following the communist revolution. Finland, which prior to the revolution had been part of the Russian Empire for over 100 years, was granted the status of an independent country, but continued to fear that the Soviet Union would demand back its territory.

Those fears quickly materialized. Following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the outbreak of the World War, the Soviets began pressuring Finland to relinquish part of its territory in order to distance the border from Leningrad. After the Finns adamantly rejected that demand, the Red Army invaded Finland on November 30, 1939. Together with other Finnish citizens, about 350 Jews were mobilized to the army to defend their country’s independence.

The Soviets were confident that the ‘Winter War’ would end in a swift victory. But the Red Army troops encountered stiff opposition and both sides suffered heavy losses. After 105 days of fierce fighting under particularly harsh conditions, during which around 126,000 Soviet soldiers and civilians and around 26,000 Finnish soldiers and civilians were killed, Finland capitulated and had to sign an especially humiliating peace agreement. Finland was forced to cede more than 10% of its territory. 400,000 citizens who lived along the common border lost their homes and had to relocate to other cities in Finland.

In June 1941, Hitler broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and invaded the Soviet Union. The Finns, hoping to regain the land that had been annexed following their degrading concession, chose to collaborate with the Germans, and the Finnish army invaded the territory that had been seized by the Soviet Union.

That is how Jews who were serving in the Finnish army found themselves in a uniquely difficult position: on the one hand, as loyal Finnish citizens who were born and grew up in the country, they set out to fight for their country’s independence. On the other hand, they were compelled to collaborate with a superpower, which after years of antisemitic legislation had embarked on the systematic annihilation of the Jews.

However, Finland was also loyal to its Jews. During all the years of their collaboration with the Nazis, the Finnish authorities refused to enact antisemitic laws, infringe the rights of Jews, or deport them from the country. Those decisions were also in force in the territories that Finland recaptured from the Soviet Union. Furthermore, right before the war, in 1938, Finland also granted asylum to Jews who fled there from the growing persecution in Nazi-occupied territories.

In July 1942, Heinrich Himmler, the head commander of the SS, came to Finland with a special mission in mind: he sought to obtain the consent of the Finnish authorities to deport the Jews and arrange for their transfer to concentration and death camps. Marshall Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, the commander in chief of the Finnish army, informed him that “no Jewish soldier from my army will be transferred to Germany. Over my dead body. The same holds true for their relatives and family members because it could affect the soldiers’ motivation.” Finland’s prime minister had the same thing to say to Himmler: “Finnish Jews are loyal citizens and we will not allow anyone to violate their legal rights.”

The only time that the Finns gave in to the demands of the Nazis was in November 1942. The chief of the Finnish State Police agreed to hand over eight Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union and Estonia to the Gestapo, whose extradition was demanded by the Germans on criminal grounds. The Finns brought the Jews to Tallin, which was already under German occupation. Seven of the Jews were promptly executed, and one managed to survive. After the media in Sweden and in Finland discovered what had happened, it caused a political uproar, after which a clear order was given by the government to prevent similar incidents from happening in the future.

The only synagogue along the entire front line, which extended from Norway to El Alamein in Egypt, belonged to the Finnish army. It was a field synagogue with an ark and a small Torah scroll that operated on the front and travelled from place to place together with the soldiers. That ark and Torah scroll can still be found in the seminary of the Jewish community in Helsinki. Jewish Finnish soldiers attended the synagogue on a regular basis, where they would openly pray and observe the Jewish holidays – oftentimes only a few feet away from Wehrmacht soldiers.

There was also one Jewish woman among them, named Dina Poljakoff. She served as a volunteer nurse for the women’s organization, Lotta Svärd, which operated in areas where the Finns were fighting against the Red Army together with units of the German Wehrmacht. In recognition of her dedication, the Germans offered to award her an Iron Cross medal. But when she realized the significance of the honor they wanted to bestow on her, she took a step back and refused to accept the medal. After the war, Poljakoff emigrated to Israel, lived in Petach Tikva, and worked as a dentist.

Besides being loyal citizens, many Finnish Jews were also ardent Zionists. Some also belonged to the Revisionist movement. Captain Salomon Klass left Finland in 1935 and emigrated to Palestine, where he joined the ranks of the Etzel underground. But in 1939, after learning that Finland was under attack, he decided to go back. From his perspective, his homeland was both in Finland and in the Land of Israel. During the war, Klass was seriously injured and lost sight in one of his eyes. Despite his disability, he returned to active duty and trained conscripts. After Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, Klass was appointed company commander in an infantry regiment subordinate to the German Army of Norway.

Even though he had daily contact with German and Austrian soldiers, Klass never hid his Jewish identity. When a high-ranking German officer visited his unit and asked him about his accent, Klass told him that his mother tongue was Yiddish. In response, the officer said “I have nothing personal against you as a Jew” – after which he did the Nazi salute and left the tent.

In 1942, after rescuing an entire German company that had been surrounded by Soviet troops, the Germans recommended that Klass be awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class, just like the medal they wanted to give to Captain Skurnik. When German officers came to Klass’s tent to award him the medal, he did not get up to greet them and told them that he was not interested in their medal because he was Jewish. The embarrassed officers responded by saying “Heil Hitler” and took their leave.

Klass remained in Finland after the war. But in 1948, like about 100 other Jews and countrymen, he utilized his military experience to fight this time for the independence of the State of Israel.

Alongside the Germans, Finland continued to fight the Soviets until the end of the summer of 1944. After the Germans sustained heavy losses and the counteroffensive launched by the Soviet army also led to regaining some Finnish territory, the Finns proposed an armistice. In September 1944, an agreement was signed between Finland and the Soviet Union. A short time later, Finland declared war on Germany and joined the Allied forces.

On December 6, 1944, Finland’s Independence Day, Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, now the country’s new president, visited the synagogue in the city of Turku. He came there to honor the memory and loyalty of the Finnish Jews who were killed defending their country.