Like many Jews, Herschel Grynszpan and his uncle Abraham were glued to the radio on March 12, 1938 when Nazi militias marched into the streets of Vienna in what would come to be called the Anschluss, the Third Reich’s annexation of Austria. Herschel and his uncle listened with great trepidation to the Austrian chancellor’s obsequious speech and the calls for revenge of Austrian citizens of German extraction. The latter spewed 20 years of acerbic poison born of the demeaning Versailles Treaty that forced Germany to kowtow to the Allied Powers.

When the Fuehrer himself entered the capital at midnight – not before stopping to lay flowers on his mother’s grave in the city of his birth Braunau – Abraham Grynszpan turned off the radio. “This is the beginning of the end,” he told his nephew with despondent eyes. Days later, the papers featured the infamous picture of kneeling Jews scrubbing Viennese sidewalks as grinning Nazi officers looked on.

Herschel Grynszpan had been living with his uncle and aunt in Paris for two years. His parents, Zondel and Rivka Grynszpan, immigrated from Poland to Germany in 1911 amid a wave of immigration of “Ostjuden,” Jews from Eastern Europe who immigrated to the land of Goethe and Schiller. Fearing for their son, they sent him to his relatives in the City of Lights.

The number of Jews under Nazi rule rose to 650,000 in the wake of the Nuremberg Laws and Austria’s annexation by the “1000-Year Reich.” These non-citizens were stripped of all rights and human dignity. They were forbidden from working in public positions, expelled in shame from universities, and subjected to daily humiliations and decrees. After Austria was annexed, Italy, Czechoslovakia, and Switzerland announced that they were closing their gates to them, adding to the immigration quotas that had already been imposed by Britain, the US, and other countries. When they most needed aid and shelter, the Chosen People found itself lacking choices. Germany proper began to issue deportation orders to Jews. Among the deportees were Herschel’s parents, his sister Berta, and his brother Mordechai Eliezer. Dispatched without food and shelter to the German-Polish border, the latter government refused to admit them.

The situation in France was also bad. The Republic that bore tidings of a revolution in human rights was among the first nations in history to grant emancipation to the Jews. It now imposed harsh immigration laws. Grynszpan was living on borrowed time in Paris without a residence permit. Having resided for two years in a Yiddish-speaking religious community and lacking contact with the French population, he failed to learn their language.

Grynszpan had every reason to plunge into deep despair. Far from his parents and devoid of rights and a future, he was a lost boy in a strange city. But the optimistic light remained in his eyes. And not in his alone. Most of the Jews living under the Reich then remained preserved their optimism thanks to events in a small, picturesque town 600 kilometers south called Evian.

The date was July, 6, 1938, 81 years ago this week. It has somehow become a historical footnote. Despite that we can consider this the day on which they began to fire up the ovens in Auschwitz. Representatives of 31 nations convened in the town of Evian at the foot of the French Alps, best known for its mineral water. Their purpose: To discuss the fate of tens of thousands of Jews living under the Third Reich. What happened there in practice was an international festival of conscience cleaning.

An abbridged list of reports from the conference: New Zealand expressed willingness to examine requests from Jews, but only on an individual case-by-case basis. Columbia said it could only absorb Jewish agricultural workers with means. Uruguay said the same. The Australian representative refused to subject his countrymen – who are known for their fragile natures – to superlative, ethical dilemmas, saying “We have no race problem now, and we do not intend to import one.”

Not wishing to inflame Arabs in the Land of Israel, Britain made its absorption of a small share of Jewish refugees conditional upon closing the Land of Israel’s gates to them. Or what Britain called a “double standard of morality.” Holland agreed to absorb refugees as long as they continued to another destination. What destination? That did not disturb their sleep. Note that America made its absorption of Jews conditional upon their presentation of certificates of good behavior from the German police. Seriously.

But the unsurpassed delivery for causing eyes to roll was that of the French representative. He cited, “the long-standing tradition of universal hospitality which has characterized her [France] throughout all her history,” saying that France would, “maintain this tradition so far as the limits laid down by her geographical position, her population and her resources permit.” However, he pointed out that “the known moral quality of the imported element” would create a sense of foreignness among French locals.

German papers reveled in headlines like: “Jews for sale cheap! Who wants them? No one wants them.” The “German Danziger Vorposten” read, “No nation is prepared to fight Europe’s disgrace [the Jews]. The conference therefore empowers Germany’s treatment of the Jews.” Another German paper, the “Nationalsozialistische Parteikorrespondenz,” declared that “Evian proves the danger that Jews pose to the world.” The British “Herald Tribune” was terser: “650,000 Jewish emigrants rejected by all at Evian.”

But the Evian Conference was more than a failure. It was the unofficial launch of the “Final Solution.” A brief perusal of Hitler’s articles reveals that he followed the conference closely, and concluded from its outcome that the world wouldn’t stand up to his decision to take irreversible steps to solve the Jewish problem.

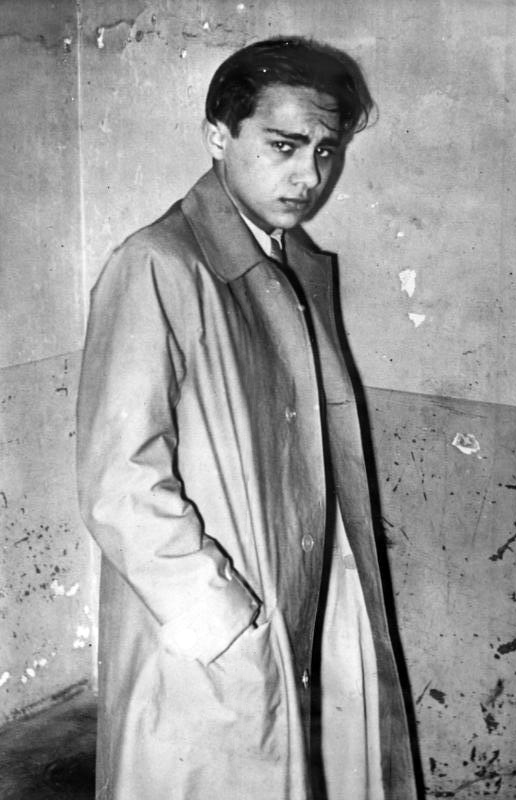

Meanwhile in Paris, the light in the eyes of a lonely and desperate Jewish boy went out. He entered the German Embassy in Paris on November 7, 1938, announcing his intention to transmit classified documents. One minute later, he shot the embassy’s third secretary and diplomat Ernst vom Rath.

“My dear parents, I could not do otherwise, God forgive me,” Grynszpan wrote on the note that he left and delivered to police, “The heart bleeds from hearing your bitter fate and that of the other hundreds of thousands of Jews. I must protest, so that the whole world hears my protest. And that is what I will do. Please forgive me.”

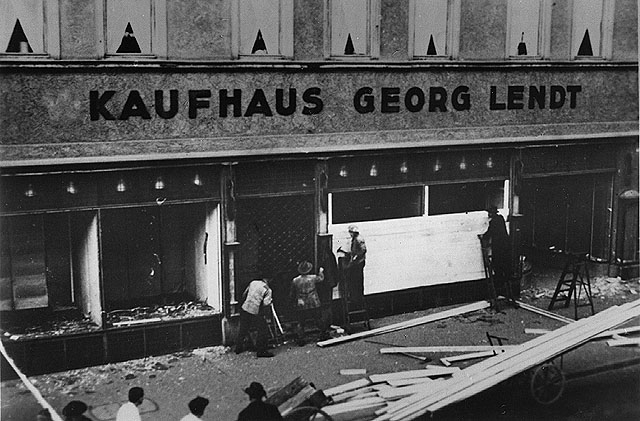

Two days later, Kristallnacht erupted.