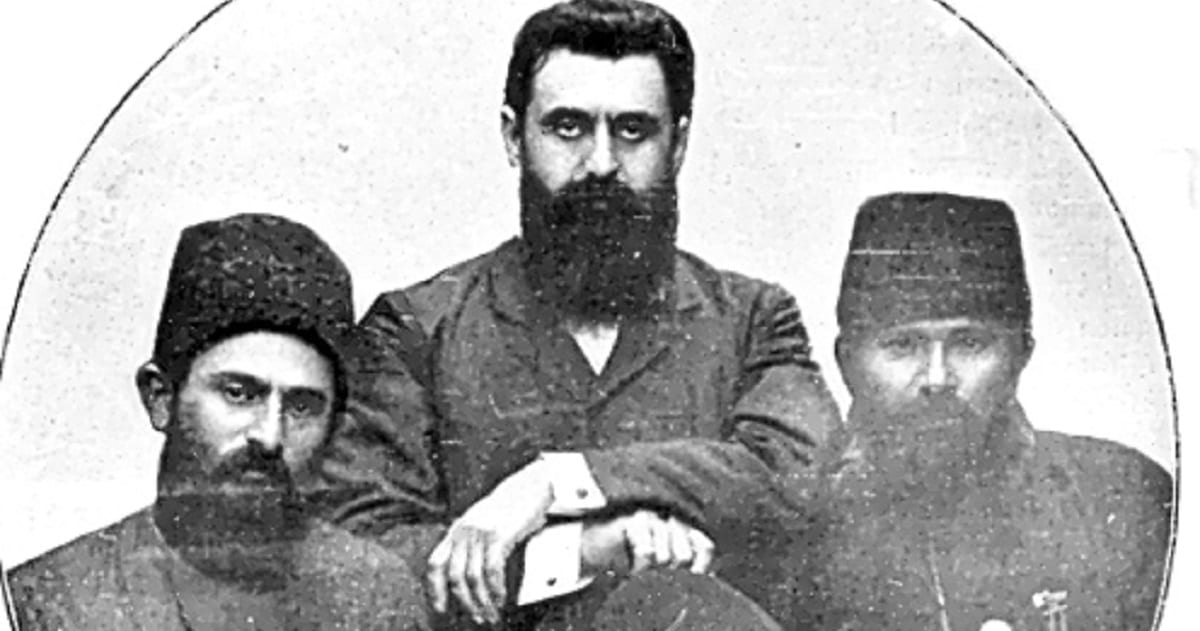

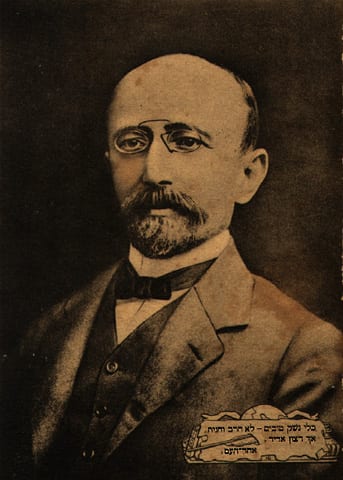

The match was about to start. In one corner of the ring, a skinny Jew with a goatee, round glasses on his nose, and a deep penetrating stare. In the other corner, an imposing looking man wearing a modern top hat and a thick beard from which only a pair of black piercing eyes could be seen, looking sharply upon reality. This was the first Titans war inside the Zionist movement, and perhaps the most crucial one, after which there were other famous rivalries such as Ben Gurion-Jabotinsky, Weizmann-Brandeis, Rabin-Peres, to name just a few.

It takes some understanding of basic sociology to grasp the conflict between Ahad Ha’am and Herzl that peaked at the beginning of the 20th Century. Ahad Ha’am’s spirit represented the Jewish civilization of Eastern Europe – millions of Yiddish-speaking observant Jews, who made their living mostly from peddling and store keeping and harbored a deep-seated longing for the Holy Land. Herzl, on the other hand, was raised in Western Europe’s cultural centers, Vienna and Budapest, in German-speaking circles who spoke the language of progress. Most of his friends and colleagues were raised in assimilated homes and had free professions and a primary desire to fully assimilate among the Gentiles.

Unfortunately, both types were rejected by the nations and perceived as a foreign element, even after the emancipation with its promises of equality and progress. Pinsker, in his seminal article “Auto-Emancipation”, compared the relations between the Jews and the nations to the situation of the rejected lover (take a guess who is the lover here).

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg, whose pseudonym was Ahad Ha’am was born in 1856 to a Hasidic family in the town of Skvyra, Ukraine. Growing up he gradually abandoned his religion, but unlike other Western Jewish intellectuals, wished not to leave his Jewish tradition altogether. As he saw it, the Zionist Movement should not merely constitute a technical solution for the Jewish people, but also a spiritual process within which the Jews are able to fulfill their moral and cultural designation to become “a light unto the nations”. Ahad Ha’am’s Zionist school is therefore called “spiritual Zionism.”

Ahad Ha’am fulfilled his vision by becoming one of the founding fathers of Hebrew journalism and by establishing the Odessa Committee which set criteria for Hebrew literature, with many disciples such as Chaim Weizmann, Shmariahu Levin and Chaim Nachman Bialik, who referred to Ahad Ha’am as his spiritual father. He is considered to this day the oracle of Hebrew theoretical writing, with works such as “The Wrong Way”, “Priest and Prophet”, and “Two Authorities”. In the mid 1890’s, he had all it took to become the unquestionable leader of the Zionist Movement according to his doctrine.

And then came Herzl – who was charismatic, magnetizing, extremely persuasive – to stir everything up. For Ahad Ha’am, Herzl represented everything he loathed: the sophisticated, Western, assimilated Jew who lacked all knowledge of the true essence of Judaism.

Let’s just say it: Ahad Ha’am was jealous as hell. During the first Zionist Congress (1897) – as he watched all his colleagues’ fascination with the charms of the new visionary – he recalled that he felt like “the only griever in the midst of a celebration”. The intellectual from Odessa certainly did not like being ripped from the leadership by the journalist from Vienna.

However, this was also a profound ideological split. Unlike Herzl, who was the father of political Zionism and introduced Zionism as the solution to the problem of the Jews – Ahad Ha’am asserted that the problem should first be solved by founding a spiritual national basis in the Land of Israel, and only then by acting in the political realm.

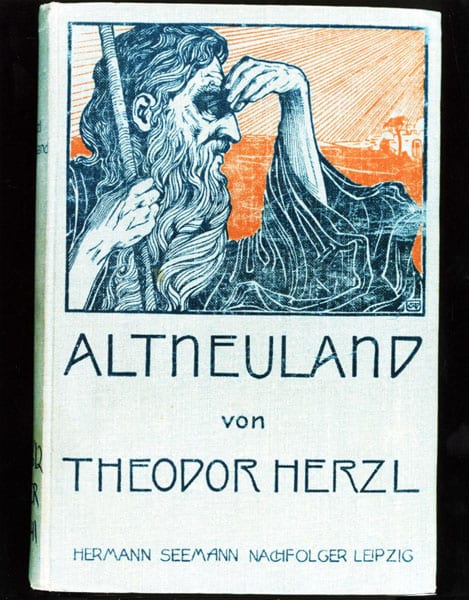

The controversy reached its peak in 1902, when Herzl published his utopic novel “Altneuland”, where he depicted the state of the Jews as a prospering nation with the newest technologies and a multi-ethnic population of Jews, Muslims and Christians, living together in harmony and speaking various languages including Hebrew.

Ahad Ha’am responded to “Altneuland” with a sarcastic essay in “Hashiloach”, and criticized Herzl’s excessive fondness for Western cosmopolitism and wish to turn the Zionist Movement into “ape’s mimics, without any unique national feature.” Deeply hurt by these words, Herzl sent his friend Max Nordau to counterattack.

Nordau, a most gifted writer, published a witty sarcastic article, personally attacking Ahad Ha’am and claiming that he was a petty, ignorant, wisdom-lacking man. The latter responded in yet another article, even stronger than the previous one. The ugly war of ideas which took place in all Jewish publications benefited neither side. Ahad Ha’am’s followers rushed to support him: “I would never have imagined that Nordau was capable of this level of monstrosity”, wrote Chaim Weizmann, the future president of the Jewish state. And Aharon Kaminka encouraged Ahad Ha’am “not to pay attention to that wicked babbler [Nordau] who disgraced you.”

Herzl’s fans aimed their own weapons at these malicious responses. Menachem Toror wrote in the popular newspaper “Hatsfira” that “the face of the Hebrew guardian has been unveiled and now we can all see the snakes crawling under the flowers he seemingly distributed,” and Max Mendelstam even encouraged Herzl not to listen to Ahad Ha’am and his “partly Asian” fans’ loud calls. Ouch.

What ended the unsightly campaign was Herzl’s premature death a short while afterwards, in July 1904. This week we mark the 92nd anniversary of the passing of Ahad Ha’am. In the battle between political and spiritual Zionism, Herzl won – big time.