The kind of bribe a leader receives or offers can reveal a lot on his set of values. Think, for example, about the elephant granted by Sultan Harun Al Rashid to Charles the Great, or the shoes that “Norman” the hustler bought for Prime Minister Micha Eshel in Yossef Cedar’s film, or the cash packed envelopes that Prime Minister Ehud Olmert received as bribe.

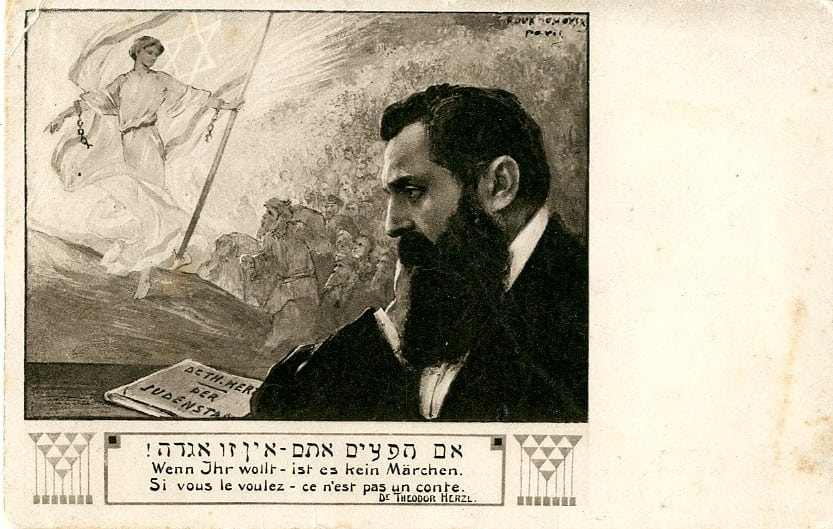

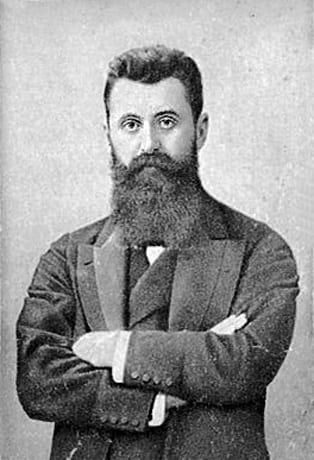

Our story begins in the summer of 1901. Theodor Herzl had a brilliant idea: to give the Turkish Sultan a present, not just any present, but the cutting edge of technology back then: a typing machine with Arab letters. Whether for mere supply and demand reasons, or out of a patronizing western approach, as Eduard Said would have called it, it is a known fact that until the early 20th century you could not find even one typewriter with Arab letters. Herzl, who marked Sultan Abd Al Hamid II as a modern Pharaoh, an addressee to the demand “let my people go”, tried to reach his heart in almost any possible way – “bakshish” (bribe) included.

Historian Mordechai Naor unfolds the story of the barter affair “typewriter for a Jewish state” in his book (הראשונים: סיפורים מן העליה הראשונה לארץ ישראל), Naor brings the correspondence between Herzl and Prof. Richard Gottheil, a world famous Jewish orientalist, that Herzl appointed as his negotiator with “Remington”, an American typewriters manufacturer. They were going to order a special work from Remington: a prototype of an Arabic typewriter, to give as an extraordinary present to the Sultan.

First they had to find the funds for the project. Remington demanded 300 dollars for the prototype, which was a huge amount, and Gottheil managed to bargain until they agreed on 150. Herzl stressed that Gottheil should keep the whole operation a secret and insisted that he rushed the Remington men, as time was a factor. Herzl realized the deadline he set for himself – end of December 1901 – could not be met.

Gottheil wrote to Herzl: “I had several meetings with the Remington people, they cannot commit on a certain date yet, the Arabic typewriter will certainly not be ready before the coming Zionist Congress, it is handmade, because they still didn’t finish all the preparations, also the special machinery essential for the assembling of the machine is still in planning stages. I will send you a telegram when I have clear answers.”

Troubles and delays did not end there, nor various technical problems. “There is a difficulty regarding the shape of the Arab letters. Although I am able to write in Arabic quite fluently, it seems that I am not capable of making a satisfying pattern from which they can engrave the letters for the machine”, Gottheil wrote Herzl in yet another letter.

Herzl located a Turkish student who helped them to make the patterns. Then the wheels got in motion, and in January 1902 Gottheil sent Herzl a telegram updating that mission was accomplished most successfully. Gottheil was so happy, “the machine works wonderfully and I am uplifted with joy for this success. I think we’re be able to ship the typewriter to you by the end of next week”. He was also happy to announce that he managed to get the Sultan’s signature, which was imprinted on the machine.

Herzl was so contented, he could not hold himself any longer, and revealed the great secret in an explicit letter to the Turkish Minister of Ceremony Ibrahim: “I am about to send a small gift to his highness the Sultan, a surprise which I hope he will like, as I believe he had seen nothing like that in Turkey. It is a typewriter with Arab letters, which I ordered especially in America. An Oriental Linguistics Professor in New York University was in charge of the engraving of the letters, which is very complicated, and I expect to receive the machine within a few weeks”.

Three weeks after the typewriter was shipped from New York to Vienna, on board the “Phoenicia”, it still has not arrived. Deeply worried and frustrated, Herzl sent Gottheil a telegram: “This is indeed embarrassing. I misled the Turks, based on information you gave me, to think that the machine will arrive within a few days, and I’m afraid Remington does not treat us respectfully.”

Two more weeks gone by, and the mystery remained unsolved. Herzl urged Gottheil to check with Remington, or with the shipping company what happened to the precious cargo. “I am full of shame, mainly because of my promise to the Turks”.

Finally, it turned out that the name on the shipment was Theodor Hirtz instead of Herzl, and that the cargo arrived to Mr. Hirtz, who also resided in Vienna, and had nothing to do with the operation. This last obstacle also removed, finally, on March 24, 1902 the present reached Herzl, who waited for it at the Rotterdam port in Holland. Herzl sent a letter to Gottheil in which he thanked and praised him for his efforts, and added: “the machine is wonderful. In a couple of days, I shall send it to Constantinople accompanied by an expert on my behalf”.

After all these torments and tribulations, Herzl was to discover all his efforts were in vain, as the Sultan simply denied the gift without a word of explanation. Though he was used to receive rejections from the Sultan, this time Herzl could not hide his insult and anger, and he wrote the Sultan a letter in May 1902, revealing how hurt he felt, that his humble gift was denied.

Many years later, when Mordechai Naor contacted “Remington” and wished to find out all the details of the story, they answered that too much time has passed and they do not have a record of the case. But it is a fact that in the beginning of the 20th century Remington started to manufacture Arabic typewriters. Naor believes it is possible that Herzl’s specially made order was the original prototype of that line. So – though Arab leader might not like the assumption – it is possible that the visionary is the Jewish state, had a great contribution to the development of printed Arabic culture.