“One of the greatest disadvantages of the human soul, and at the same time one of its deepest subtleties, is its inability to be revealed unless through the body,” wrote the Argentinian author, Ernesto Sábato, in his celebrated novel, On Heroes and Tombs.

Sábato, who lived and worked in South America in the second half of the 20th century, said more than once that Franz Kafka was his most admired author. It is not hard to understand why. If ever there was a master of analyzing the human soul by means of the body, it was no doubt the gifted Jewish author, Franz Kafka, who died 97 years ago this week, alone and isolated, in the city of his birth – Prague.

In his essay, “Kafka’s Wound,” Prof. Shahar Galili wrote that “the special weight of Kafka’s writings is inherent in his relentless attempts to transfer the question of the body to the writing system.” Kafka was ashamed of his own body. Thin and too tall, with large ears, an aquiline Jewish nose, and dark, protruding eyes. In one of the letters he wrote to his friend Milena, Kafka shared the shame he felt every time he had to take off his clothes at the swimming pool and expose his scrawny and frail body. According to Prof. Michael Gluzman, “Kafka felt he was a stranger inside in his own body. He saw himself as a corpse floating in the river and felt mortally ill many years before he contracted tuberculosis.”

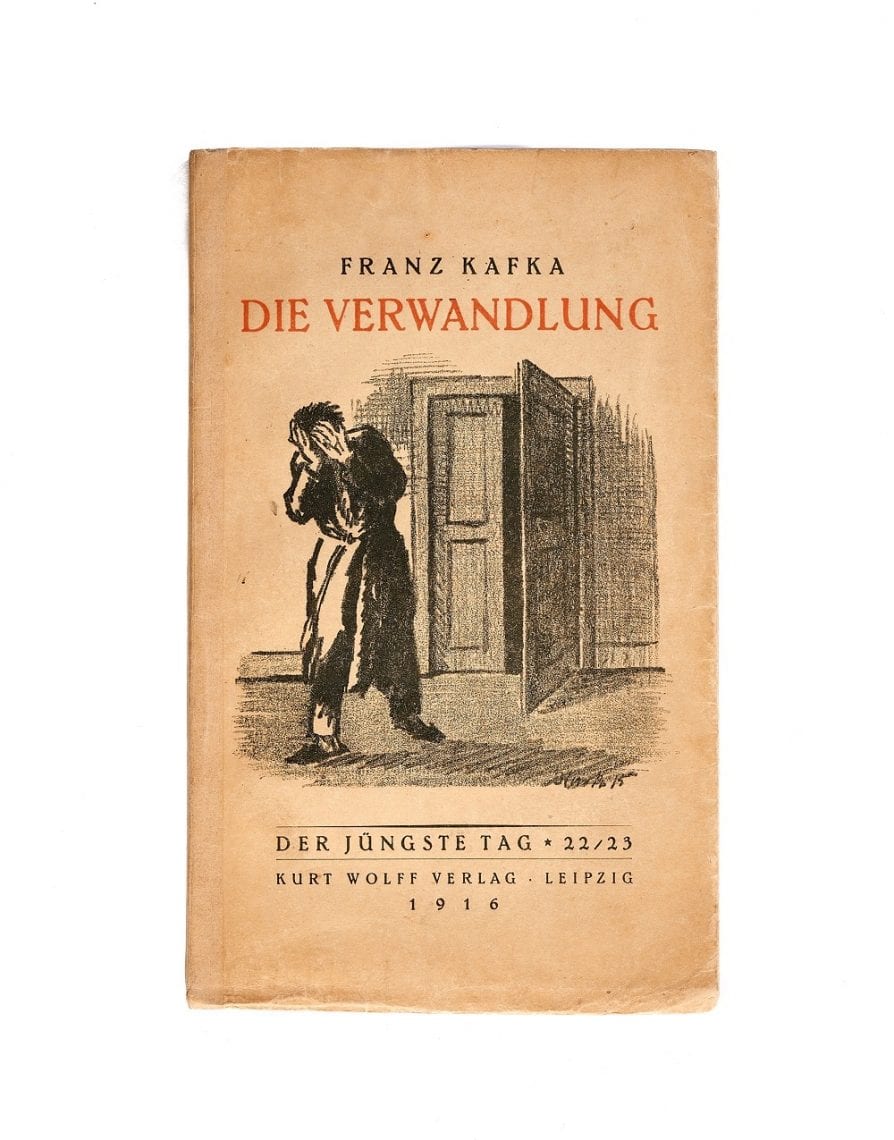

One of the poetic tools used by Kafka in his works is the transformation of the human body into forms of other animals. A man who turns into a dog (Investigations of a Dog), a mouse (Josephine the Singer) and a monkey (A Report to an Academy). These are a select collection of the transformations into animals that filled his writings. However, his most famous work belonging to this genre is undoubtedly the novella The Metamorphosis, which Kafka began writing in November 1912. And thanks to a great burst of creativity, he finished it in just a month.

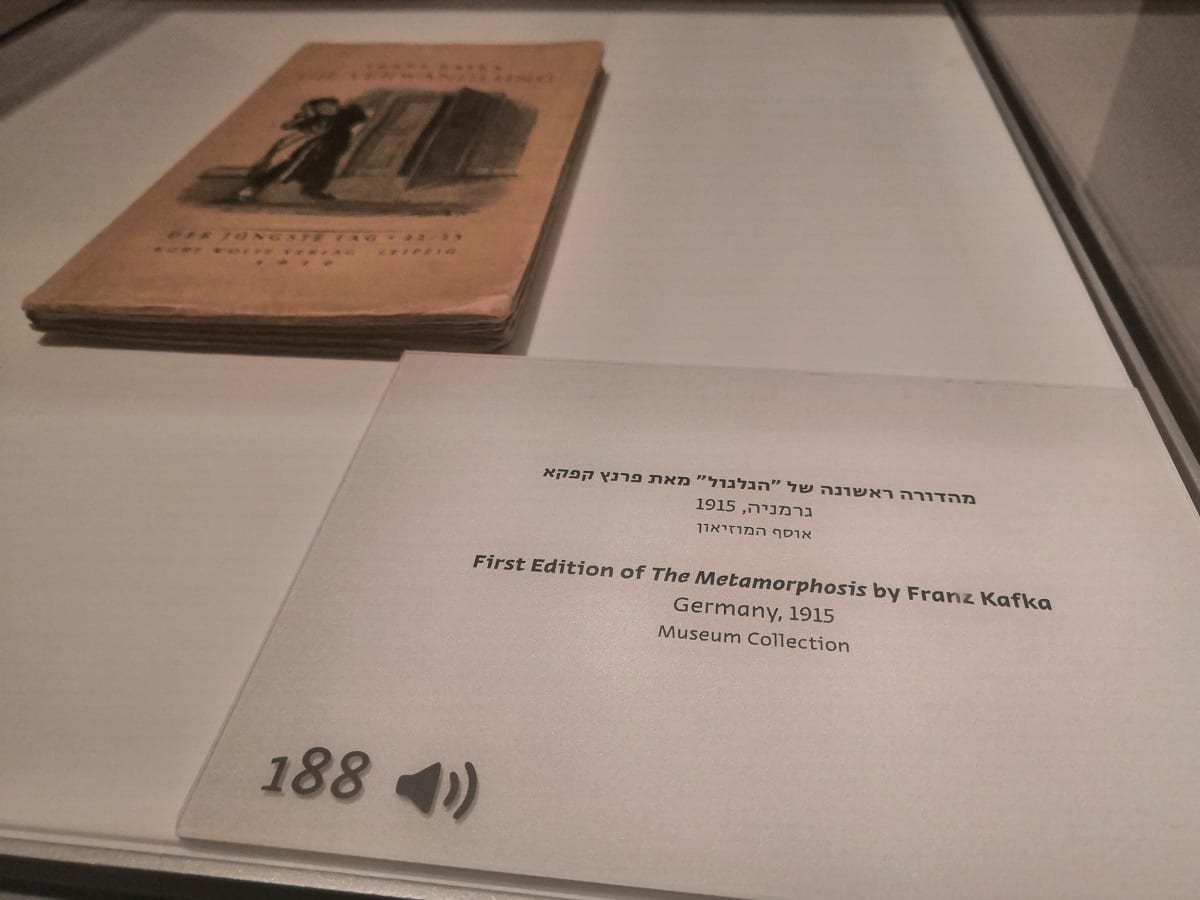

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed into a gigantic insect,” is the opening sentence of The Metamorphosis. A copy of its first edition is on display in the new exhibition at ANU-The Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv, together with more information provided by Prof. Galili in the special audio guide highlight tour that reviews the new museum.

The full extent of the Kafkaesque charm is embodied in that short and compact sentence that opens The Metamorphosis. A man gets up in the morning and suddenly discovers that he is a vermin, an insect, a cockroach. That episode interrupts a banal and ordinary life routine and surprises Gregor Samsa, a nondescript insurance salesman, and the people around him. The fantasy is described in a cold and neutral tone, which is the secret of its magnetic power. The transformation of Gregor Samsa into an insect is not an illusion, allegory or nightmare, but rather a realistic story. Apart from the fanciful episode, all the other details in the novella are consistent with the everyday and mundane routine that characterizes the life of a lower middle class urban family, who go on with their ordinary way life despite the extraordinary event.

Researchers agree that Kafka’s negative body image was influenced by anti-Semitic stereotypes that were prevalent in that period. For example, the historian, Sander Gilman, notes that the book Sex and Character was high on the list of best sellers in Austria at the time. It was written by the assimilated Jewish philosopher, Otto Weininger. In his anti-Semitic manifesto, which relies on eugenics theories (breeding the master race) combined with classic self-hatred, Weininger maintains that the Jews are a effeminate, weak and debased race. “Women and Jews lack a rational and moral self. Therefore, they are not worthy of or entitled to equality with Aryan men, or even to simple liberty.”

The film “Nosferatu” was first screened in Germany a decade later. It is about an ugly vampire with a mouse-like face, crooked nose and dark eyes, who sucks the blood of fair-skinned Aryan girls. The equation of the vampire with a Jew left little to the imagination. Julius Streicher, who would later become the chief editor of Der Stürmer – the propaganda-replete newspaper of the Nazi party, attended the festive premiere of the film. Captivated by the Jewish image of the vampire, Streicher went to the movie theater every day. His impressions were translated into caricatures of vampires of Jewish origin, which he would feature on the pages of the newspaper. The stereotype of an effeminate and weak Jew described by Weininger was turned into a blood-sucking vampire by Streicher. The transition to the image of an insect or a vermin did not take long.

So perhaps Kafka was ahead of his time and The Metamorphosis was actually an inadvertent prophecy about the fate of the assimilated Western Jew – the Westjuden. Did the Jew’s success in integrating into the fabric of European life cause him to fall into such a deep slumber that he woke up one morning perspiring, only to discover that he was regarded an insect?

Kafka researchers do not agree on the Jewish weight in his works. We know that Kafka was trapped in a limbo of contradictory identities: he was an author of Jewish origin, lived in Bohemia and wrote in German about universal themes. No one disputes that Kafka had a warm place in his heart for the Zionist movement, that he studied Hebrew, and that the circle of his closest friends, including Max Brod and Hugo Bergmann, were all Jewish. On the other hand, there is evidence that he found the Jewish stereotype repugnant.

“I thrive among all the animals,” he wrote while vacationing at his sister’s country home. “This afternoon I fed the goats. These goats, by the way, look like thoroughly Jewish types, mostly doctors, though there are a few approximations of lawyers, Polish Jews.” On another occasion Kafka expressed his disgust for a young, half-pious Jew who was resting right under his balcony: “He lies in his reclining chair, comfortably outstretched with one hand over his head and the other thrust deep into his fly, and all day long cheerfully keeps on humming temple melodies.”

But more than anything else, it was the distress that stood out, which was so typical of that generation of Jewish creators who felt they were strangers in both the Jewish and the German space. “Most of the young Jews who began to write in German wanted to leave their Jewishness behind them and their fathers approved of this, but vaguely,” Kafka wrote to his friend Max Brod. “But their hind legs were still fastened to the faith of their forefathers and their front legs were groping for, but not finding, new ground. The resulting desperation became their inspiration.”

The desperation became a source of inspiration, but his tuberculosis-ridden body was unable to hang on. Kafka once said “we Jews are born old.” Maybe because he was born old, Kafka did not see any point in living past 41, his age at the time of his death. The Metamorphosis proves that even though his body has not been with us for 97 years, his spirit and works will remain here forever.