As Prof. Israel Yuval was standing with his three daughters at the bottom of the deep cistern under the famous basilica in the German town of Trier, he felt it was a life changing moment for him. 900 years beforehand, at that very spot, Jewish parents were willing to throw their children into the pit before the crusaders walk into town. The awe that held him as he was picturing the horrid view, set Prof. Yuval on a pioneering research journey at the end of which his article “Revenge and Curse – Blood and Libel” was published, in 1994. It was a daring, revolutionary work that questioned the very origin of the Jewish victim consciousness that peaked in the blood libels first appeared in the middle ages.

Until Yuval’s study, any attempt to crack the Christian psychology behind the blood libels was considered an act of heresy in the religion of Jewish martyrdom. But Yuval, born to a religious family and leaving religion as an adult, was not intimidated. By all means, he did of course try to find justification for the horrible libels; he simply wished to understand, as a Jew, why the libels occurred specifically in the 12th century, among Ashkenazi communities in Europe.

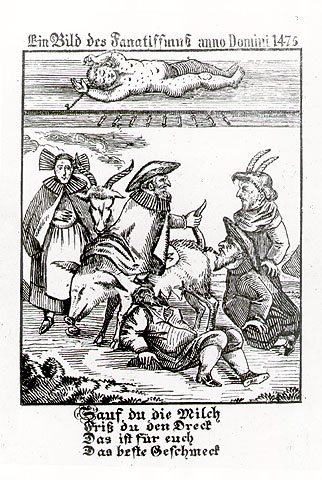

Most historians agree that the blood libels spread in medieval Europe were a dramatic phase in the evolution of Antisemitism. It was always the same story: just before Passover a Christian child was found dead, usually by the local river or stream. The local jurists would soon conclude that the Jews slaughtered the child for their ritual needs, especially baking Passover Matsot from his blood. Prof. Yuval proved that the first blood libel occurred in the city of Würzburg, Germany in 1147, whereas the Norwich affair, usually referred to as the first, was in fact two years later. He also showed a correlation between the Würzburg affair and riots that were performed in the area a few decades beforehand and deeply affected the Jews. Those were the Rhineland massacres of 1096, during the crusades in German communities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz on the Rhine River.

The massacres are horrifically described in three Jewish chronicles. The Jews had two choices: convert or die. Thousands were burnt at the stakes. The Jewish extreme respond was martyrdom, either by surrending and getting killed by the crusaders, or by committing suicide.

Heroic suicide exists in Judaism since ancient times. Though strictly forbidden by Halacha, it is told in martyrdom stories such as Hannah and her seven sons, and the Roman siege on Masada. But this time it was different: dozens of mass suicides of Jews, and even worse – mothers slaughtering their babies, fathers burning their houses and killing their entire families: and parents throwing their children into the icy river.

This, according to Yuval, did not just occurred, it had Messianic fundamental background which characterized Ashkenazi Jewry, and included some bloody fanatic fantasies what were in the center of the redemption ideology, which Yuval calls “Revenging Redemption”, as opposed to the redemption of Sephardis, that emphasized the utopic end of times, when all nations would come to Jerusalem and become Jews. The Revenging Redemption was inspired by Midrashic stories describing how the martyrs’ blood is splashed on the Lord’s robe and when it’s all soaked, The Lord will revenge and hurry the redemption. Therefore the killers (of their children) are heroes that hurry the redemption. He cites many sources, such as Kalonimus, and famous verse Pour out Your wrath upon the nations from the Passover Hagadah.

The none-Jewish society was not indifferent to these expressions of Jewish martyrdom. Historian Mary Minty in her essay “Visualizing Jews Through the Ages: Literary and Material Representations” reveals Christian sources showing that the Christians authorities were aware of phenomena and feared it greatly. This brings us to the circumstantial relation between the Jewish “Kidush Ha-Shem” and blood libels.

Prof. Yuval asserts: “the centrality of the blood rituals in the collective mind of the generation after 1096, as well as the disapproving Christian attitude, shed new light on the emergence – exactly at the same time -of a new, twisted and hostile, interpretation to this ritual: the blood libel.” And he adds a fascinating explanation: in the Christians’ frightened minds, if the Jews are able to slaughter their own children to rush the Salvation, what’s to stop them from killing Christian children before their holiday of freedom? In fact, Yuval’s thesis puts the libels into a historical context. For him, the blood ritual embedded the Ashkenazi theology led to Christians fearing the Jew’s thirst for blood, hence to turning the Jew from the victim to the offender.

Happy Passover!