Much like other bygone vocations that did not survive the technological revolution, a photo studio is one of the institutions that have been vanishing from the public sphere. The dark room, film strips, the hard labor of photo development, the thrilling expectation to find out how the photos turned out – have been replaced by digital cameras installed in mobile phones, allowing every talent-lacking young brat to be cameraman, director, designer, developer, and distributor of photos.

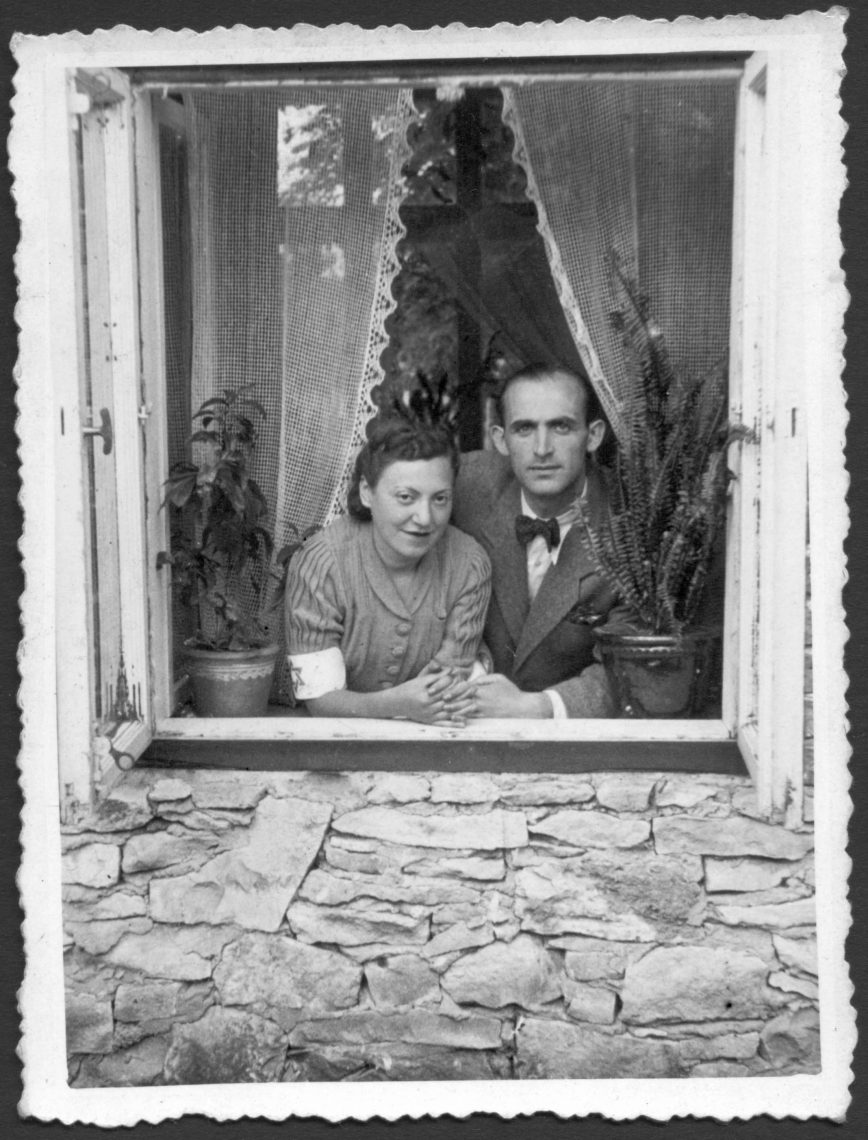

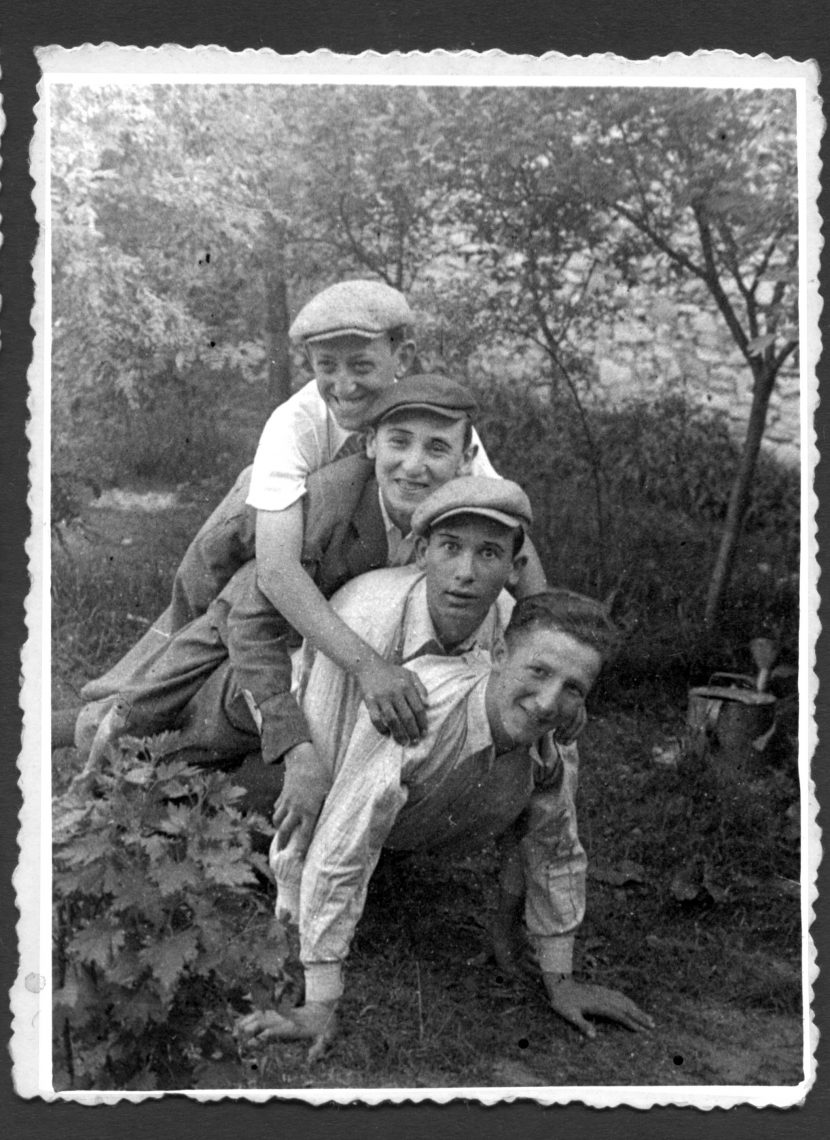

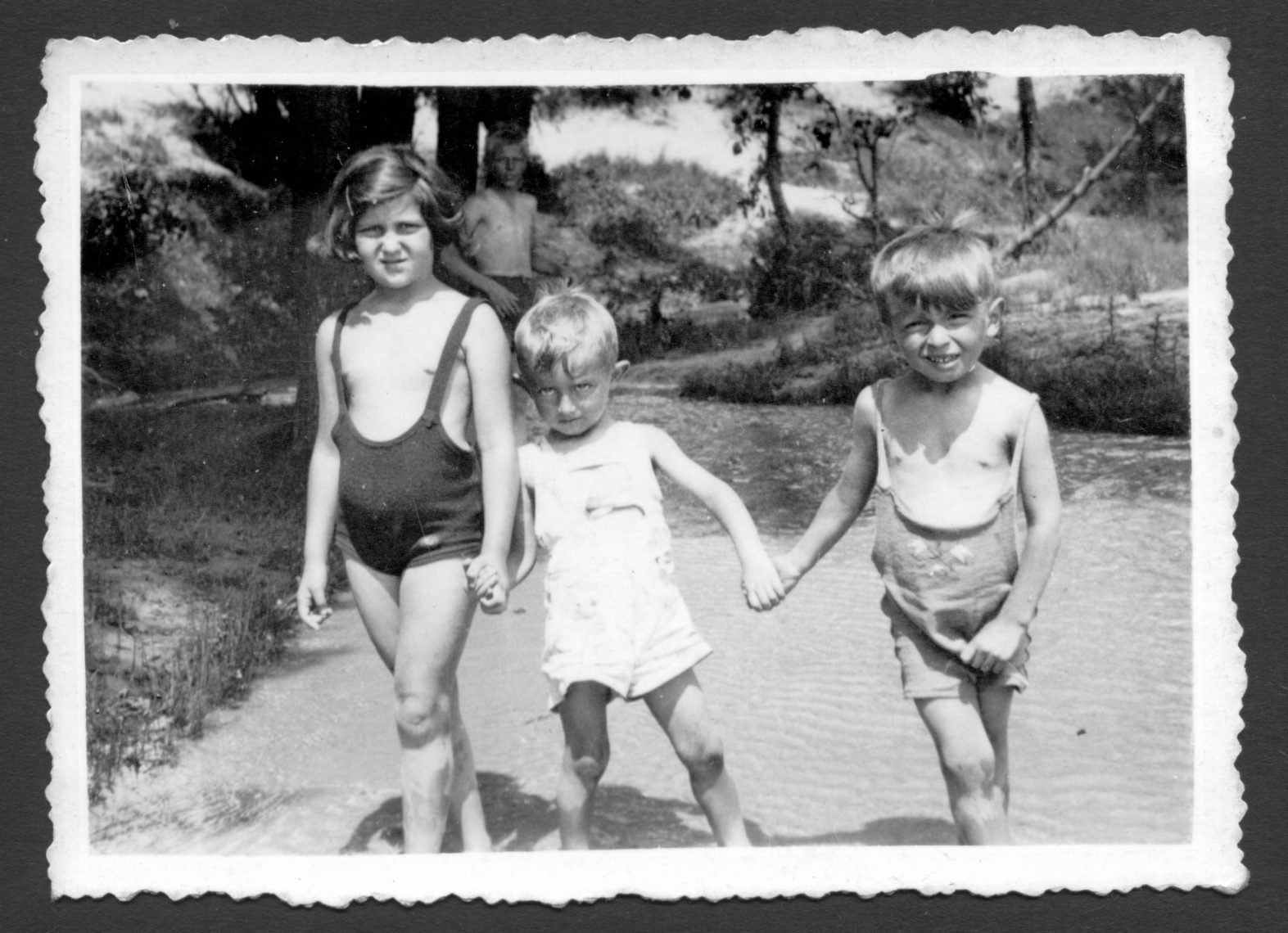

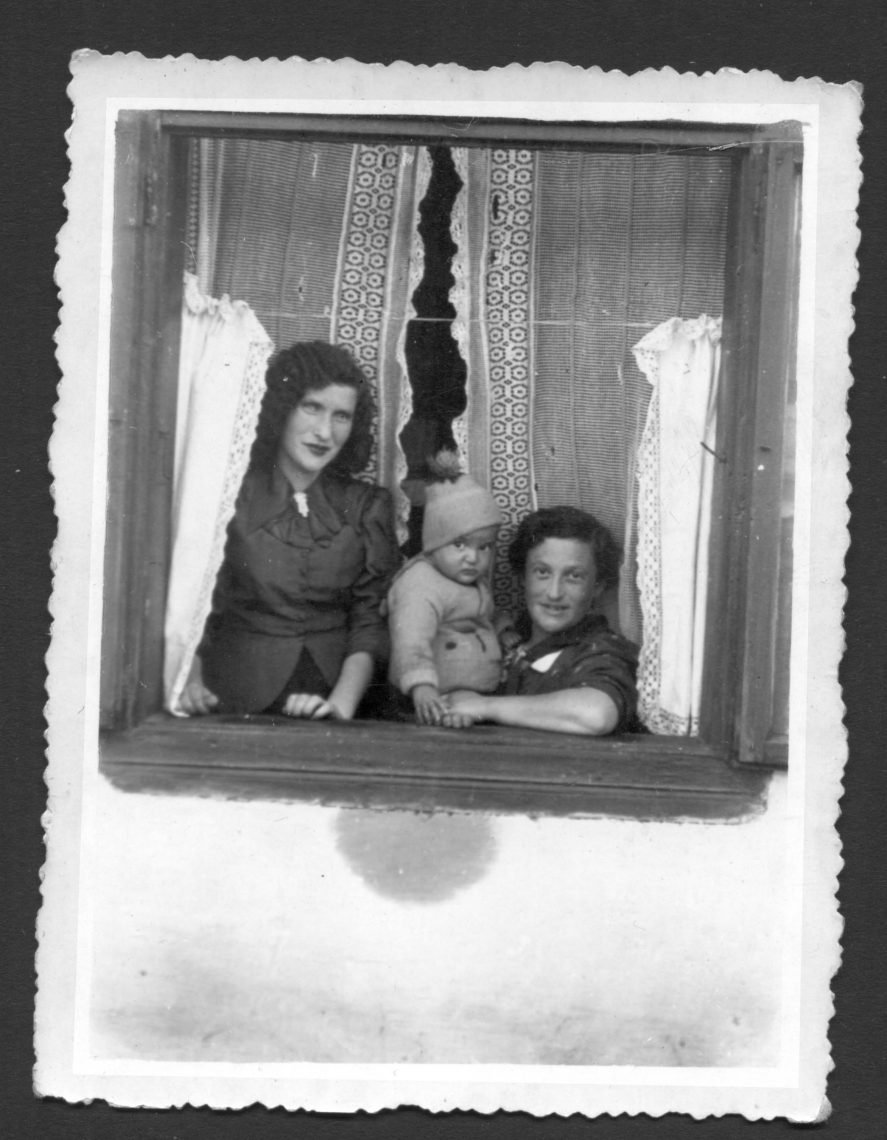

But this is the story of a whole different kind of photographer: Jozef Bacior, who owned a photo studio in Żarki, Poland. Bacior was an artist, who had two sets of eyes: the materialistic eyes, and the spiritual eyes. What he saw in his mind’s eyes, he captured – restlessly – in his blue hawk eyes. He did it each moment, and in every location, especially outdoors, in the picturesque scenery of his town, Żarki. Bacior devoted all his skill and passion in photographing the 3,000 Jews of his hometown, realizing deep inside that these were the last photos of all his Jewish friends and neighbors.

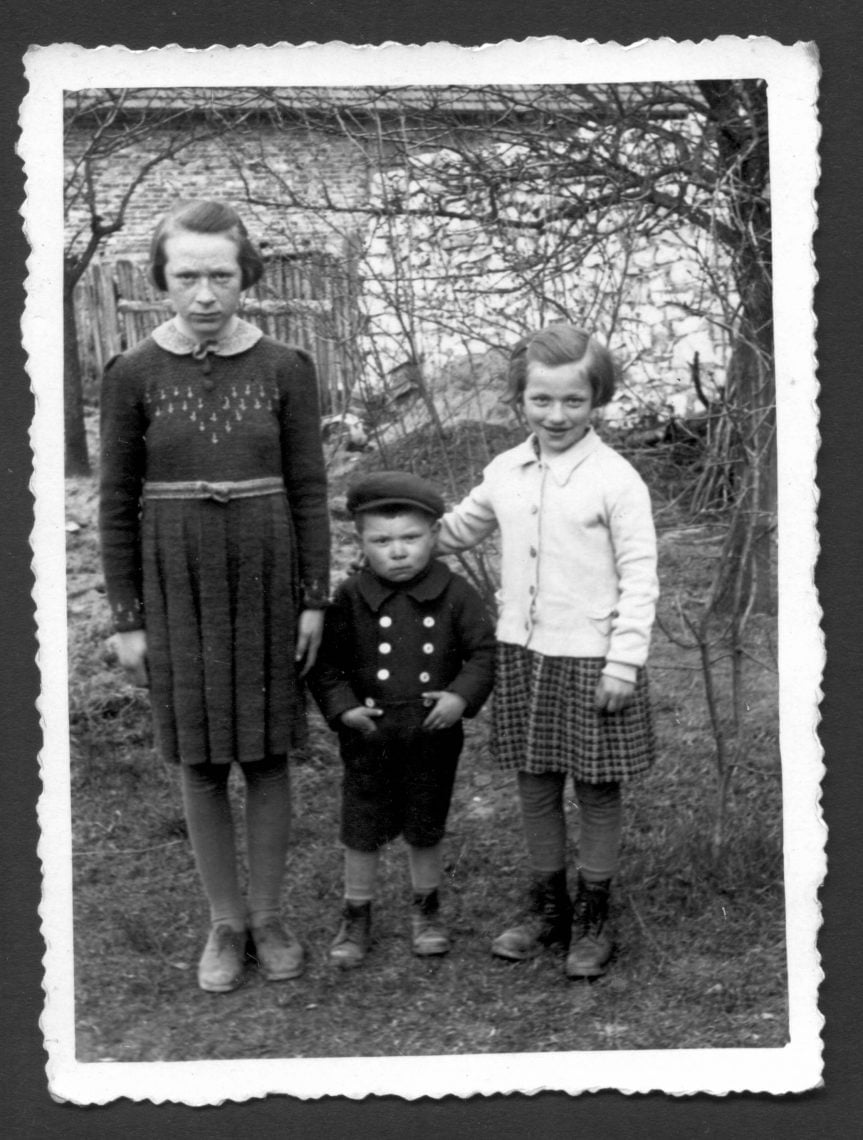

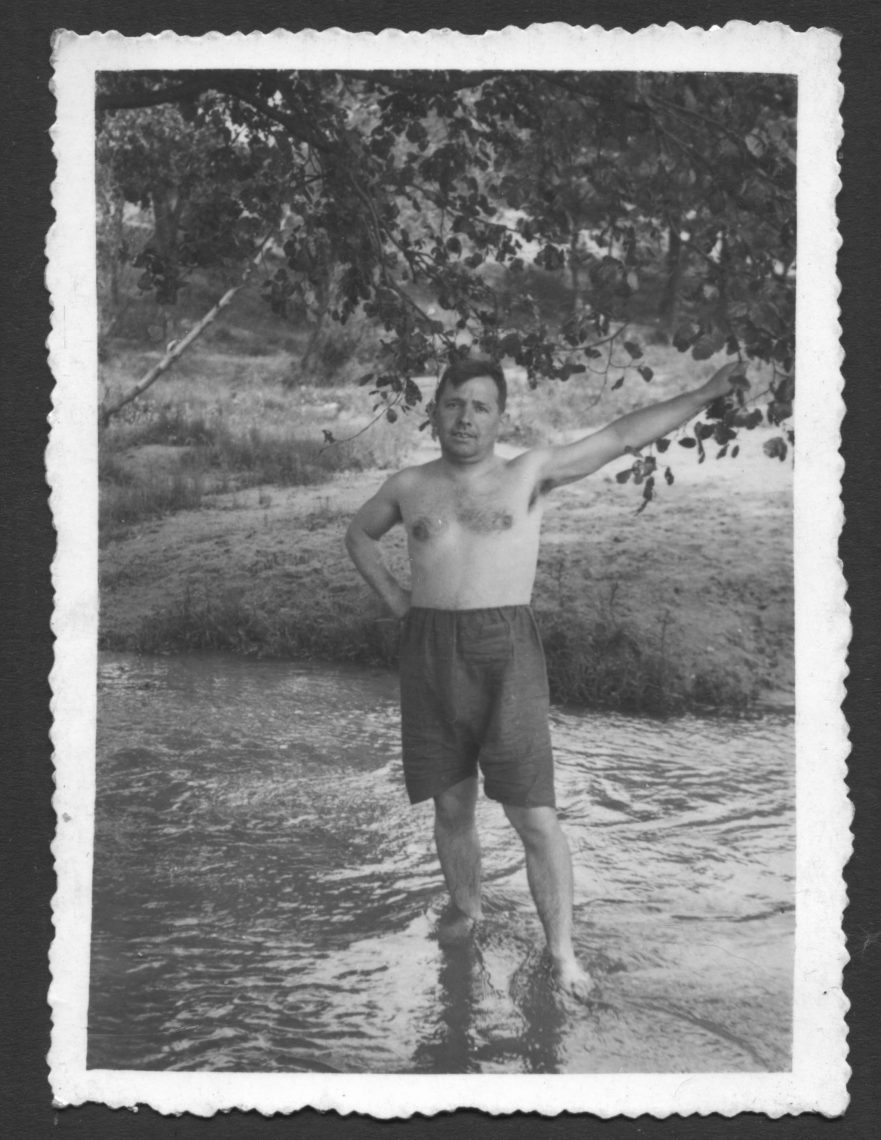

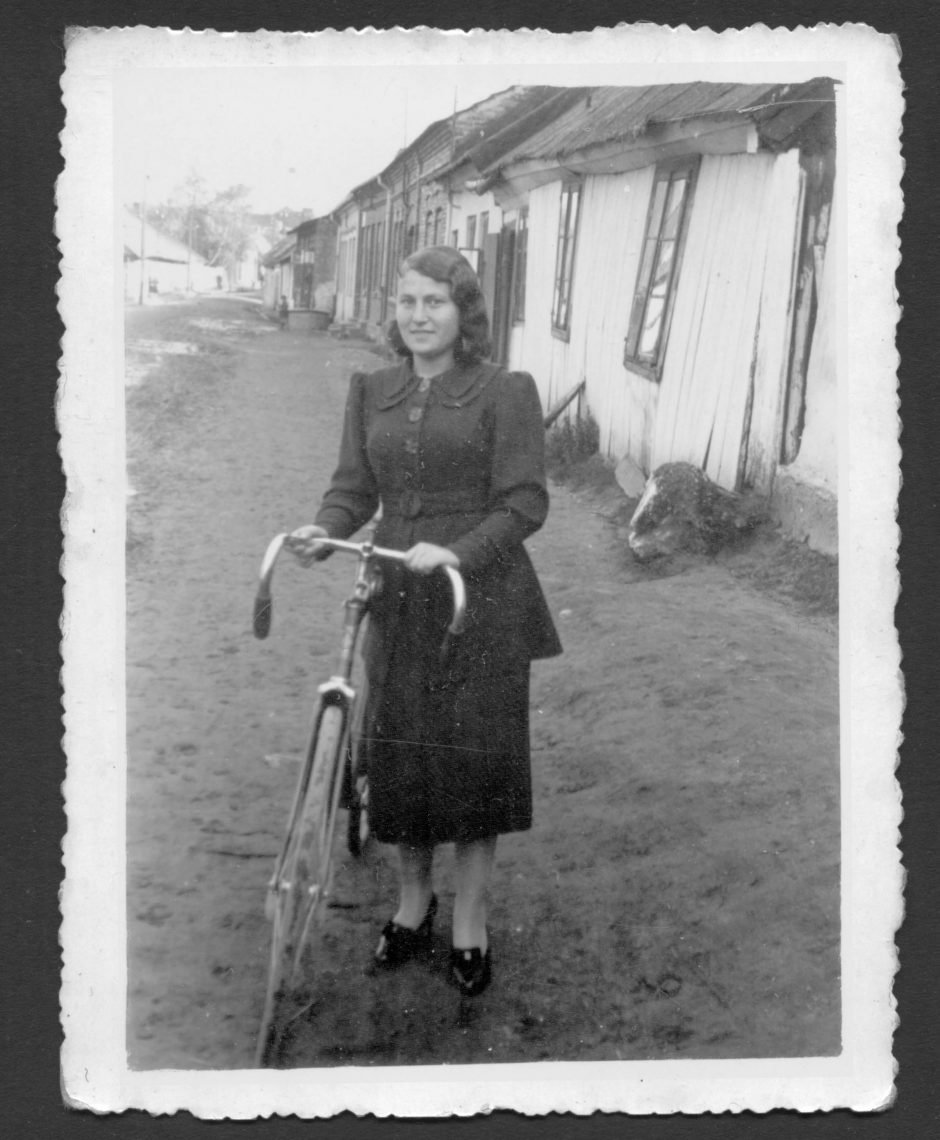

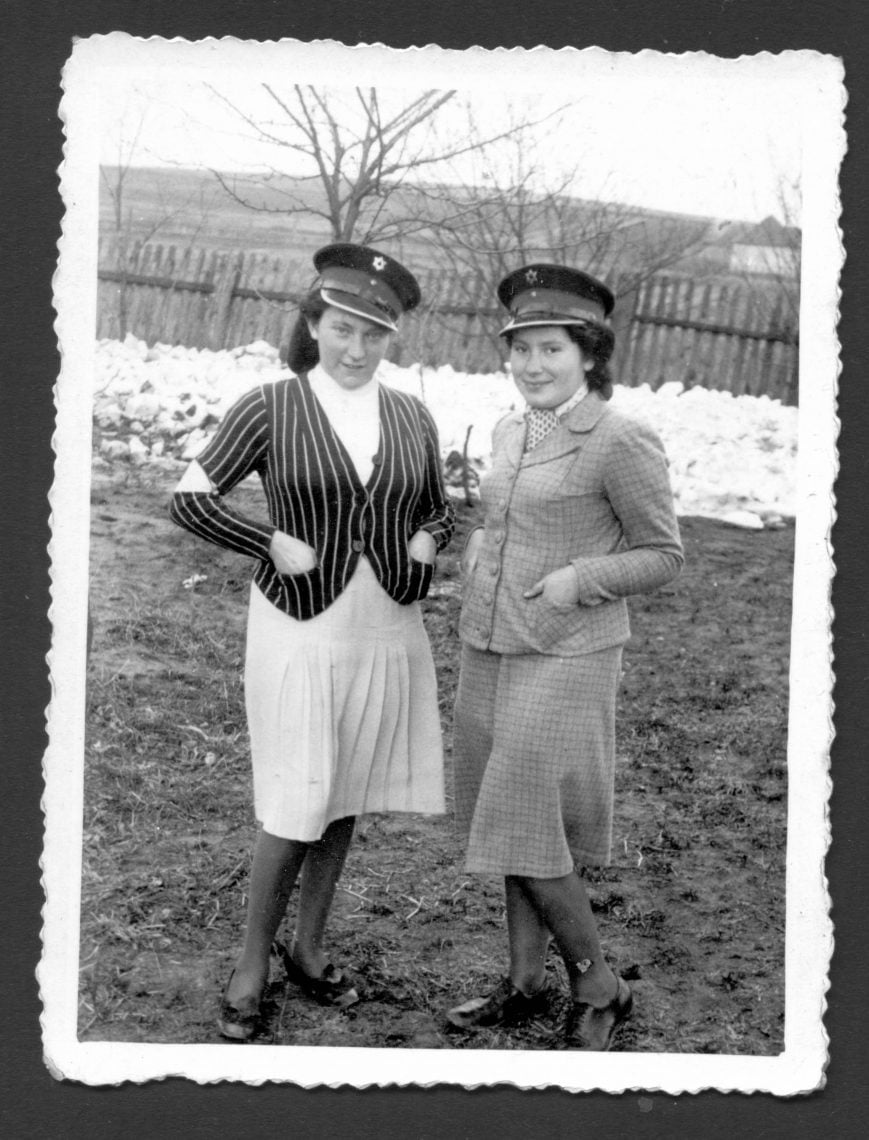

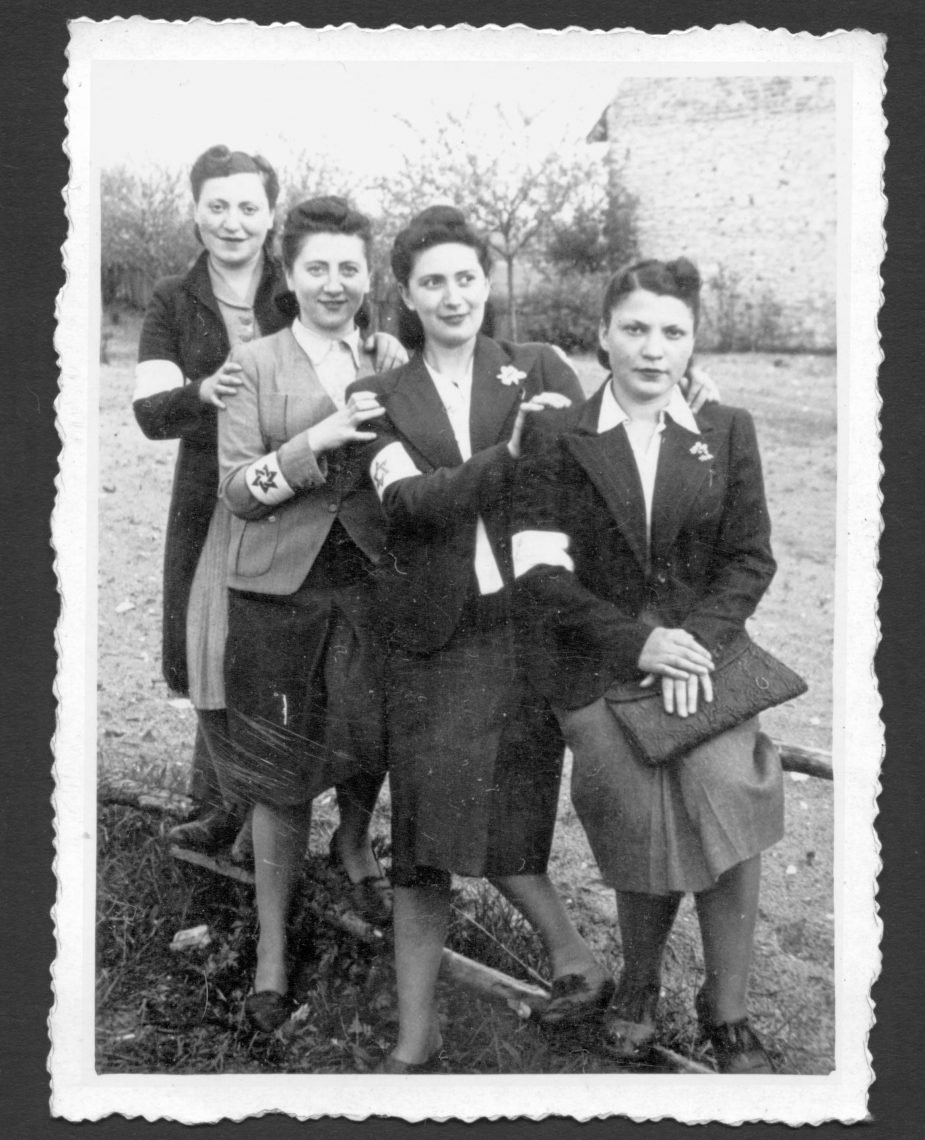

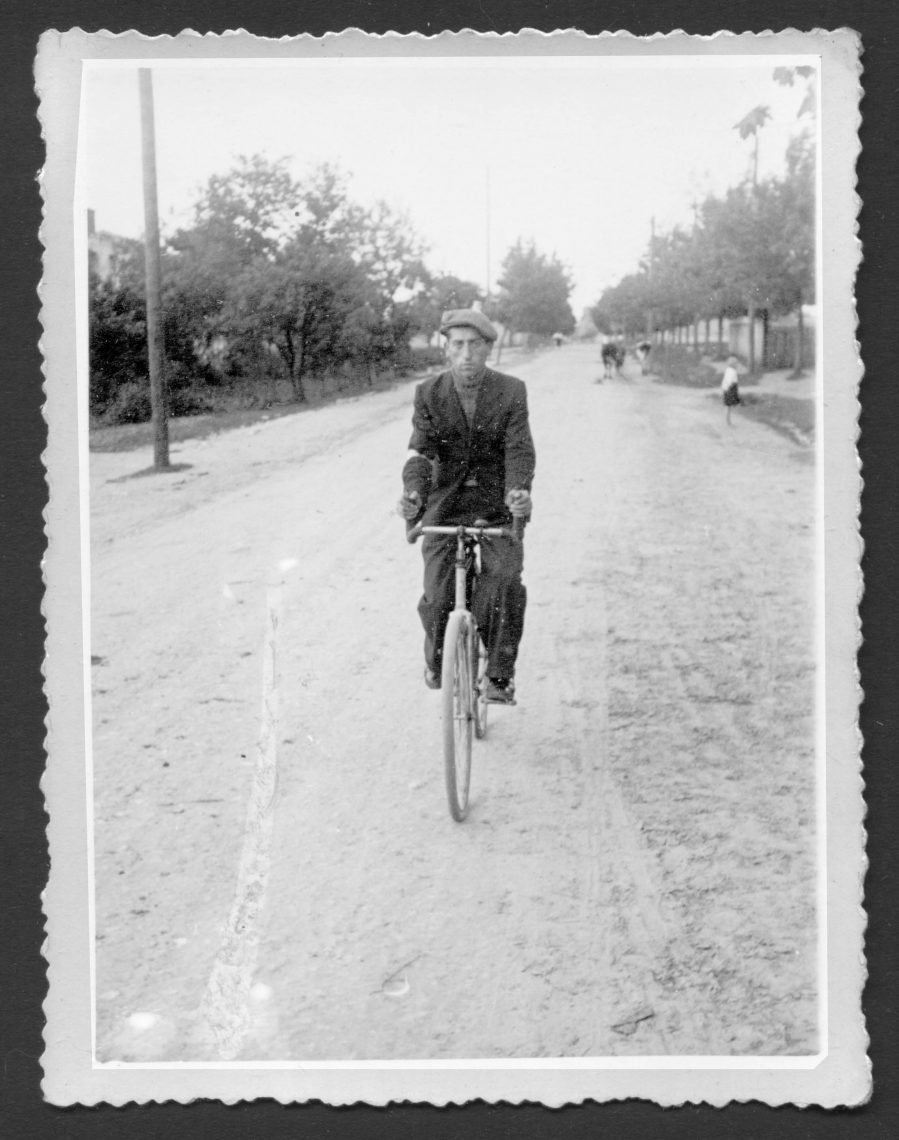

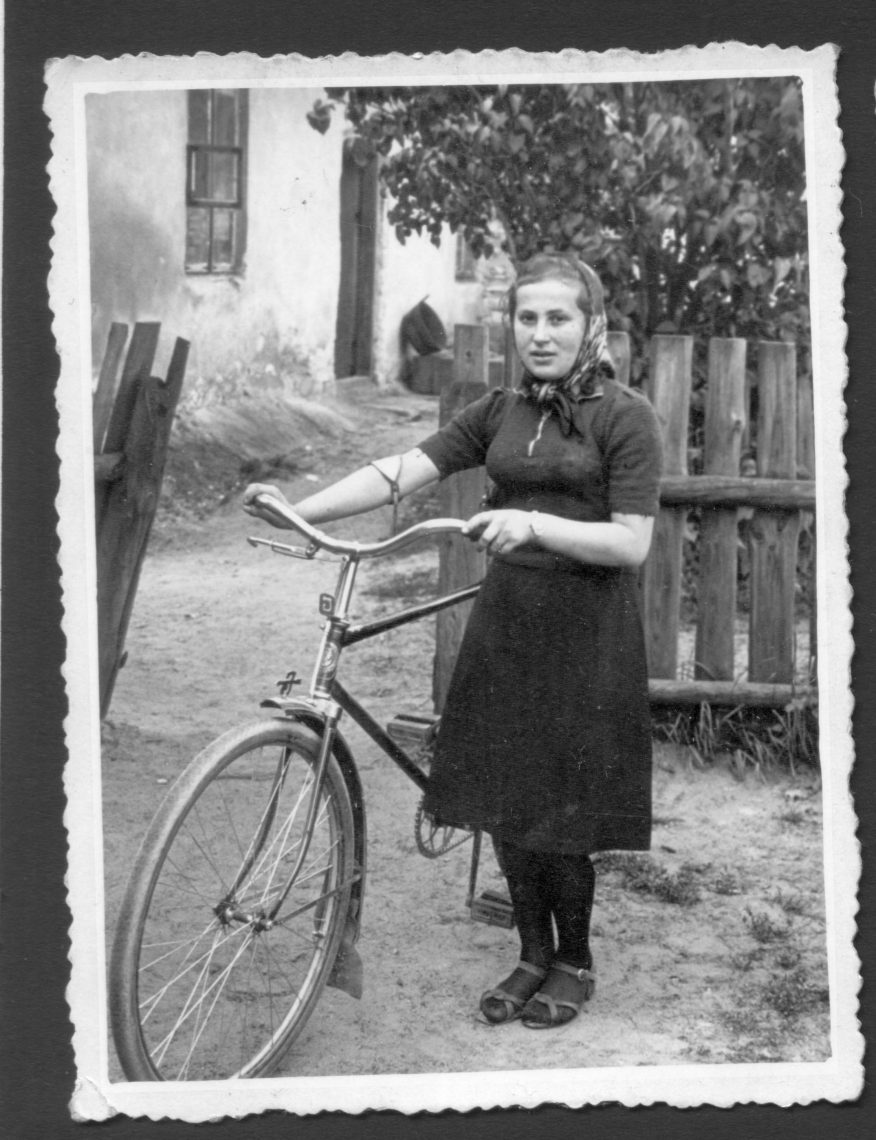

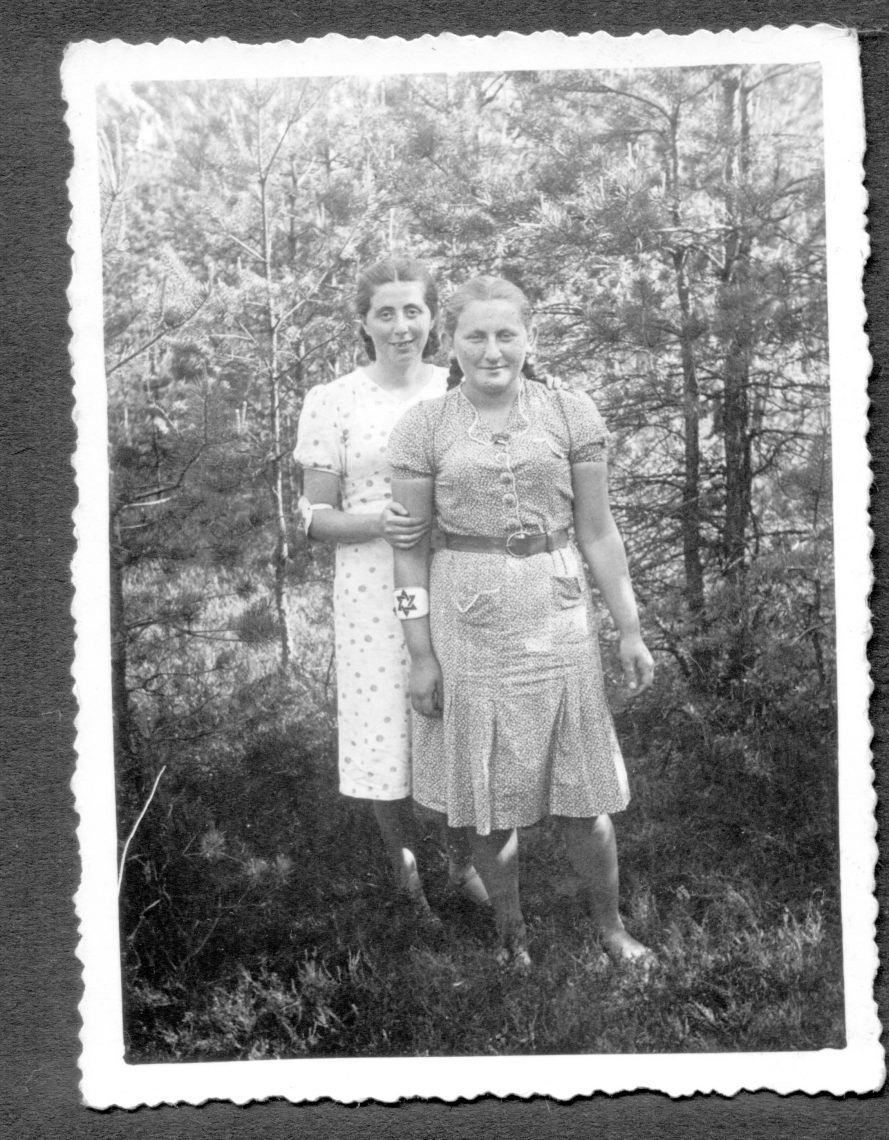

It is agreed that artistic photography is supposed to encourage the viewers to complete the missing details in their minds. The missing gaps in a photo are far more intriguing than what is actually shown. Jozef Bacior took over 700 photos, documenting the Jews in a wide range of human situations – relaxing on vacations, laughing, studying, retreating, spending time with the family, friends, working, celebrating, and so on – seemingly everyday photos that portray normal people doing normal things. But a closer look reveals what we do not directly see – they were all taken during the Nazi occupation in Poland, from 1939 until 1942, while in the meantime, the most horrific human tragedy was taking place.

Amidst the raging war out there, Bacior was miraculously able to ignore the context, the background sounds, the injuries, the humiliation, and the abused dignity, that were the share of all his Jewish friends in Żarki during the war, and chose to present them as people living life to its fullest. This hair-raising dissonance is what makes Bacior’s photographs collection such a precious treasure, that tugs even the toughest people’s heartstrings.

How Bacior’s photo albums were found starts, just like any classic Holocaust story, in an attic. Jolanta and Woiciech Galecki were clearing their father’s apartment in the city of Bendin, Poland. Upon reaching the attic, they discovered an old dusty box inside a drawer, and when they opened it, they realized they’d struck gold – over 700 photos, marked at the back as the property of Helena and Joshua Najman, a Jewish couple who used to live in Bendin. After further inquiry, Jolanta found out that his father and Joshua Najman were good friends, and that the latter asked him to keep the photos until the war was over. Then the collection was passed on to the Brama Cukermana Foundation, whose researchers, after a profound investigation, found out that the photos were taken by Jozef Bacior in the town of Żarki. However, how the pictures ended up in the care of the Najmans from Bendin, was never detected.

What’s most unique about the Jozef Bacior collection is its documentary point of view. Most of the Holocaust visual documentation was done by the perpetrators. German soldiers who were amateur photographers took tens of thousands of photos during the war, which were the primary source, while the second source was professional photographers who served in special Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS units.

Yet another source of documents came from the Jewish victims, who shot and filmed in central ghettos such as in Warsaw, Lodz and Kovno, for example the “Photo Forbert” shop in Warsaw, that documented the ghetto’s welfare institutes; the private collection of Mendel Grossman and Henrik Ross, Jewish photographers who photographed life in the Lodz ghetto; and the album by Zvi Kadushin, of photos from the Kovno ghetto. These albums, it is quite understandable, were created in order to record the Holocaust itself, the very essence of the horrors and history of the period. But the Bacior collection is different. It defiantly ignores the tragedy and focuses on life itself. Furthermore, we do not know of another photo collection taken by a non-Jew who was not a German, that is as rich and original as the Bacior collection.

One more eerie feature of the collection is that all the people in the photos are anonymous. In spite of their relentless efforts, the researchers could only identify one man, Mordechai Weinryb, who survived the war and lived in Israel and in Germany. None of the hundreds of others could be identified. It is assumed that most of the Jews of Żarki were sent to Treblinka in October 1942 and perished in the Holocaust.

Holocaust Memorial day draws us all to a collective traumatic state of mind, almost automatically. Still, we must not forget – and the Bacior collection is an excellent, unique reminder – that the story of the Jews of Poland is not just their tragedy, but also the happy, creative, vibrant and dynamic life that preceded it.

The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot is proud and thrilled to share with our readers that in recent days, over 300 photographs from the Jozef Bacior’s collection were sent to us by the Brama Cukermana Foundation in Poland.

All photos courtesy of Brama Cukermana Foundation