Some stories are so remarkably fantastic, that all you wish is to find out whether they are real or fake. So when I interviewed Judit Polgár in a Café in Budapest a few years back, I had to ask her, was it true that she never attended school? Indeed, she confirmed that she, like her two elder sisters before her, attended school for less than one week a year, only so that they could take the exams. She did go to kindergarten – but only for a slightly longer period.

The story of Polgár and her sisters has captured the imagination of many fans worldwide since the 1980s. Brought up from a young age to become a chess champion, in controversial educational methods invented and used by her father, this prodigy girl proved all theories about genius – though she refuses to be defined as a genius. She proved that genius is not just a genetic but has much to do with environment and education. And most and foremost, she showed that women can reach the highest level in the rational field of chess like men can, as she reached the world sixth place and defeated 11 world champions, including Garry Kasparov and Magnus Carlsen, the legendary world champion since 2013.

Yet Polgár – who became a symbol of some different trends – certainly cannot be held within any firm definitions. To start with, she does not define herself a feminist. She claims there are congenital differences between men and women in regarding to Chess, especially professional Chess in the highest levels, which is surprising to hear from someone who proved the opposite.

“In my time there were hardly any women in professional chess. Today, in the young ages I often see more girls than boys”, she said in a former interview. “But then, around the age of 12, something changes. Perhaps it can be explained by girls’ early social maturity, during which they start referring to chess as no more than a game or hobby, while boys take achievements and competitions very seriously.”

Polgár sure did not consider chess just a game. At 13, she was already rated top woman player. And this is a feminist act, even if she did not think it was. “When a boy my age got two good results, they talked enthusiastically about his talent, but with me – it’s like they always waited for additional evidence, or expecting the whole thing to fail at some point. They said, what if she has a boyfriend and be distracted? What if she marries and lose interest? But I never did.”

Indeed, she never did. Polgár marry quite young, at 24, and had a son and a daughter, while competing in world matches. If feminism is first and foremost a state of mind, then there is no better example than Polgár. In the late 1970s, Garry Kasparov said that there was no chance for a woman to become world champion. He took it back and admitted his mistake three decades later, even if it wasn’t Polgár to win the title.

As part of his strategy, Judith’s father refused to have her compete in games for women only. When she was 16, her parents turned down a fashion campaign offered to her by GAP.

Another ideology Polgár is sometimes considered representing, is home schooling. But it does not mean she doesn’t believe in schools. After retiring from professional chess, she initiated a program for children focusing on studying by chess, which is part of the official curriculum in many schools in Hungary for ages 6-10, applied also in the Chinese education system. It is important to stress, that the program does not teach chess, nor does it seek to raise chess stars, but using chess as a means of improving children’s abilities.

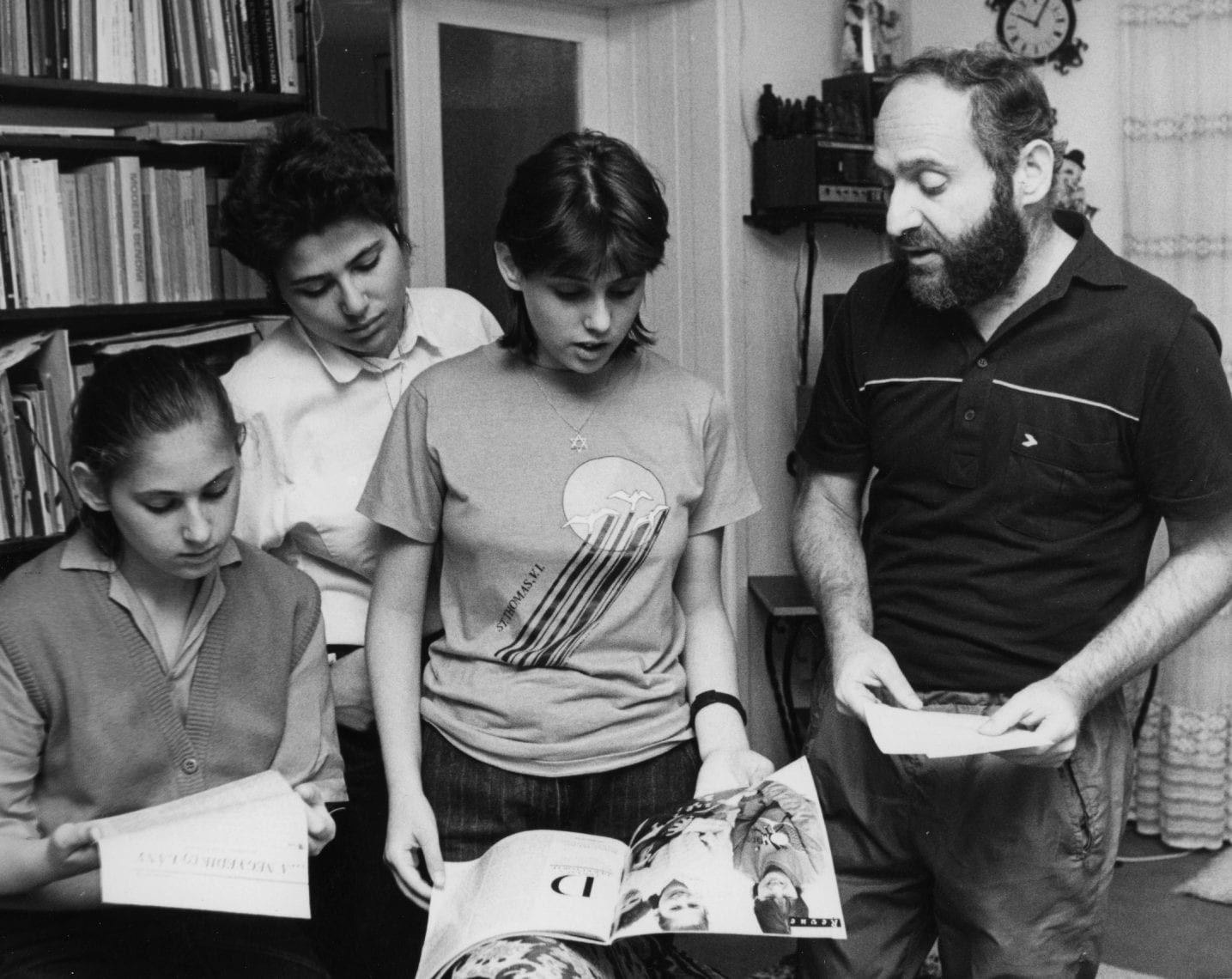

She explains her parents’ extreme decisions in the great changes occurred since her childhood. Judit grew up in communist Hungary. Like most Hungarians back then, her family was poor with very little financial opportunities. Her father László, who was a mathematician, invented a home schooling method that he thought could produce genius, and her mother Clara cooperated. Originally, chess was not even part of the program, not until their oldest daughter, Zsuzsa, while still their only child, first showed interest in the game.

Polgár understands her parents. “sure, they could have done one thing or another differently, but they gave us as much as they could.” But she fears that people might take her as an example without fully understand all aspects of her story. “People has the tendency not to look deeply into things. My story is sometimes twice misunderstood. First, most people do not capture the huge commitment of such a process. My parents gave up all their personal goals and inspirations. They never went on a vacation and spent all their resources on books and teachers for us. Many parents think they can commit, but only few would go that far. Neither I, nor my husband, who is a veterinarian, would be willing to give up our careers. The other thing having a clear vision and a carefully detailed action plan. It’s not just deciding on home schooling; it is about knowing exactly what you are doing at any stage. Naturally, I’m better in chess than my sisters because I was the third, and my parents already gained experience from their previous two processes.

Judit’s elder sister, Susan (Zsuzsa) was rated first world champion for women and Sofia too was a professional world level player who won masters tournament in Rome when she was 14, and shortly after left the field of chess.

When Judith was 12, at the winter of communism in Hungary, her father agreed for all three to constitute the Hungarian team for women in the chess Olympics. The soviets, who took pride in the communist education techniques, looked down on László Polgár, yet Hungary won the championship, which is considered to be a huge national milestone in the years of liberation from the bonds of soviet rule. Judith won 12 games and one draw.

Though Judith is a proud Hungarian, she is also an affiliated proud Jew. Both her grandmothers survived the holocaust, her grandfathers were in forced labor camps where many Jews perished. She is a national hero in Hungary, who speaks a lot of her Jewish origins, participated in the Maccabia, has an Israeli citizenship and visits Israel, where her parents and sister Sofia live.

Perhaps she is exceptional, being a girl prodigy, then a woman champion, but all in all, Jewish success in chess is not an unusual thing. As Judit says: “kind of like the violin, chess is both intellectual, and easy (and cheap) to carry, therefore it suits the constant wanderings of Jewish history”.

(Translated from Hebrew by Danna Paz Prins)