Catherine the Great, the Tsarina of Russia, was known for her insatiable lust. Legend has it that in her twilight years she grew tired of her lovers and turned to four-legged animals to satisfy her sexual needs. Those legends also claim that she went to her maker in the midst of passionate relations with a horse.

The legends were refuted, but no one denies that Catherine the Great urges were overwhelming. During her rule, she was obsessed not only with sex – but with conquering nations, pathological collection of art, and familial murder. Historians maintain that she was behind the assassination of her husband Peter III, and even schemed to kill their son Paul I, ordering that shards of glass be put in his food.

But Catherine’s greatest nemeses were the hundreds of thousands of Jews crowded into the Russian Pale. Catherine loathed the Jews and did everything she could to embitter their lives. In 1791, she issued an extraordinary decree to retract the citizenship of most of Russia’s Jews, doubled the taxes of urban Jews in comparison with their Christian neighbors, and forced rural Jews to move into cities – thus turning them into what she called “effective Jews.”

In his lecture on “An Attempt to Understand the Foundation of Anti-Semitism,” writer A.B. Yehoshua argues that comprehension of the anti-Semitic pathogen rests in the implications of man’s deep-seated perverse, dim, and repressed inclinations toward foreign elements in society. He believes that only this explains the profound hatred of the Jewish People, who were the ultimate “stranger” and “Other” for hundreds of years. Did Catherine the Great project her dark urges onto the Jid – the Slavic expletive for Jew? Let Yehoshua answer. Maybe.

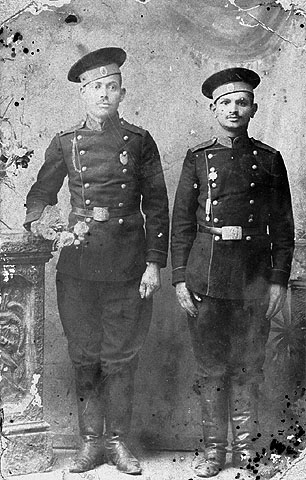

What is certain is that hatred of Jews flowed in the Romanov veins. In 1804, Catherine’s grandson, Tsar Alexander I, established the commission that drafted the “Enactment Concerning the Jews.” Their first meeting opened with the following: “The Jews are the foreign element fundamentally responsible for the socio-economic problems in Russia’s West.” But Alexander’s brother, Nicholas I, was the worst of all. Appointed Tsar in 1825 and called by the Jews “the Russian Haman,” he was highly displeased that Jews did not enlist in the army, and in 1827 ordered that all 12-year old Jewish boys be drafted for 25 years. These children lived under harsh conditions and strict discipline in military training facilities until they turned 18 and were inducted in full military service.

They story of the children who came to be called “the Constantines” gave rise to one of the most shocking phenomena in Diaspora Jewish experience– one that resembles the events in 1939-1945. Like the Nazis who imposed their dirty work on the Judenrat, Nicholas I forced the leaders of Jewish communities to fulfill quotas of recruits.

Their parents were poor, but not stupid. They knew that the implication of drafting their sons for 25 years was permanent separation. One of Nicholas’s main goals was to baptize the boys in re-education centers. He did not only strive to separate them from their biological parents but from their Jewish identities. In “The Memoirs of Yehezkel Kotik,” Kotik cites the “shotgun weddings” that were common in those years, when poor parents married little boys as young as six in haste to spare them from the draft. He wrote that some parents actually cut off their sons’ trigger fingers.

The need to meet these quotas is permanently etched in Jewish history in the form of the ignoble occupation of those called “haperim” in Hebrew and “hatfonim” in Yiddish. Their job was to kidnap little children from poor families for conscription. Kotik describes this as an “unbearable sight,” the most horrific acts witnessed by Jews. He wrote that the Jewish kidnappers arrived in the shtetl unseen. That they appeared before the police with government permits identifying them as hatfonim. That the police assigned the necessary soldiers to assist them and at midnight, they began knocking on doors. If the doors failed to open immediately, they busted them open and broke the locks by means of special tools that they carried with them. That they came in quickly, brutally dragged out the young man, and left at once.

Kotik wrote that in his shtetl of Kamenets there were three hatfonim, and that one of them, Aaron Leybel, was murderously cruel and lacking a trace of mercy. He noted that he was accompanied by two men, Hezkel and Mushka, and that it was their job to kidnap eight-year-old boys.

The hatfonim’s salaries were paid by community leaders per head. These leaders eventually tried to soothe their consciences by claiming that the kidnapping of the children was taxation of the poor in return for the years of welfare that the wealthy Jews had provided.

In his book about the Russian Constantines, Yosef Mendelevich highlights the practical influence of these acts on these families, noting that the mothers died of broken hearts and that fathers were physically maimed by their struggle with the hatfonim. He writes that the sobbing and keening of these families screamed to the heavens.

A new king arose in Russia in 1895. But unlike some kings in biblical tales, this was a good king. Alexander II, Nicholas’s son and the great-grandson of Catherine the Great, was called “the good Tsar” and “the Liberator.” He broke the family’s anti-Semitic chain. He introduced far-reaching reforms on behalf of the Jews, granting equal rights to Jews and – most important – overturning the Constantine Decree.

But the fear remained and, despite the 160 years that have passed, we still pray on every Pesach that some Nicholas or Catherine or other despot will rise up to destroy us. May it be a happy holiday and most of all void of decrees