Gefilte fish is probably Eastern-European Jewry’s most famous dish. Other well-known Jewish delicacies include borsht, bagels and shmalz. Today, however, not many are aware that the names of these familiar foods are also Jewish surnames, as are babke, kishke, tzimes and more. There are at least a hundred Israelis with the family name Herring, and over one hundred people in the U.S. bearing the last name Schmalz.

Some family names originated from Yiddish terms such as Gitflaish (“good meat”), Vaisbroyt (“white bread”) and Feferkichen (a spice cake, sometimes translated as “gingerbread”). Others, such as Weisskraut (“white cabbage”) or Sauerapfel (“sour apple”) derive from German. Polish gave us such surnames such as Herbata (“tea”), Czosnek (“garlic”) and Obarzanek (a type of bagel), to name a few.

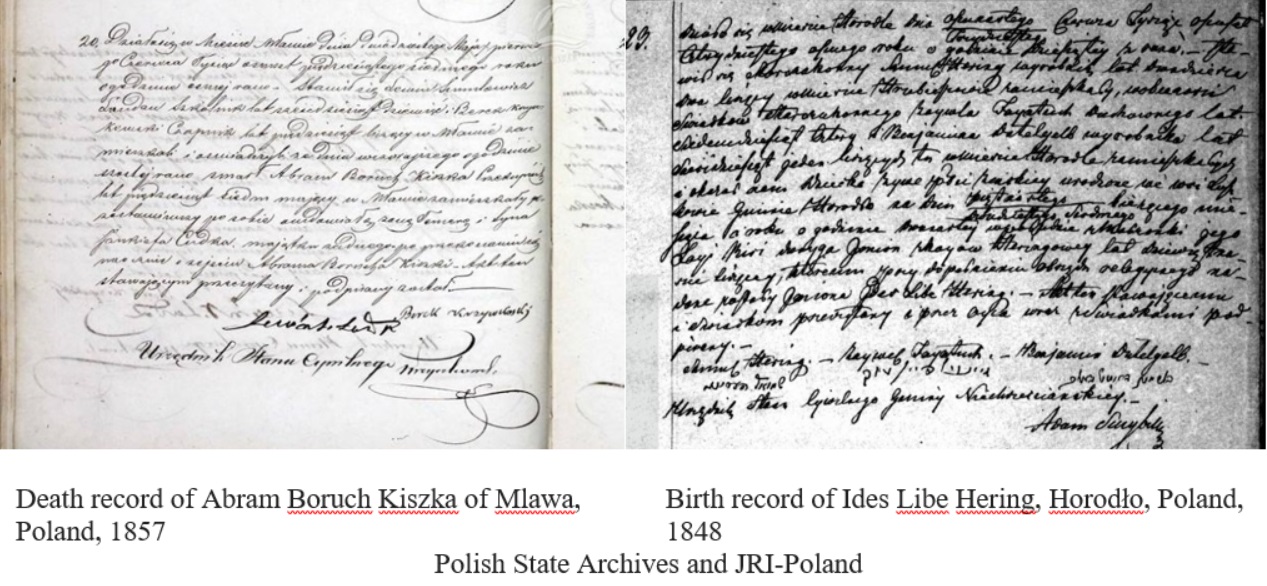

Our ancestors in Eastern Europe had a special relationship with their food, as reflected in some of the family names that were adopted in the 19th century. Surnames deriving from Jewish dishes, spices, drinks and more were common among Eastern European Jews, especially in Poland, Galicia and in the Russian Pale of Settlement. An examination of this little-known onomastic category sheds light on Jewish historical culinary traditions and offers insight into the lives of Ashkenazi Jews.

From biblical times, Jews had lived without family names. There was neither halachic requirement nor Jewish tradition wherein blood relatives shared a last name and passed it from generation to generation. The adoption of surnames by the Jewish population in Central and East European countries during the first decades of the 19th century was a result of legislation imposed upon them by the authorities of their countries of residence.

The use of a kinnui (“nickname”), on the other hand, had been widespread among Jews across the globe since ancient times. The term kinnui was also applied to the adoption of vernacular or secular names, and it was common for many Jews — men and women, young and old — to be known by a nickname that was given to them by family or community members.

These nicknames were derived from a variety of sources. Some reflected a physical characteristic such as height – Lang (“long”), Kurz (“short”), while some described other personal attributes such as Blinder or Shlepak (both meaning “blind”), Taube (“deaf”) and Grau (someone with a “grey” beard or hair). Other nicknames referred to intellectual abilities – Kluger/Kliger (“wise”/”clever”), Gelerter (“learned,” “scholar”) or to the socio-economic status of the person – Bednjak (from biedny, the Polish for “a poor man”) or Gazdag (“rich” in Hungarian).

Bearing a nickname linked to an occupation, meanwhile, could have served as a business card. Impoverished parents needed to repair a pair of shoes so that a younger sibling could use them? Yankel Schuster (“shoemaker”) was the address. A broken window? Yosl Gluzman (“glazier”) was the expert. A challah for Shabbat? Moishe Semmelman (“roll maker”) had the best prices in town.

What about a gourmand who enjoyed his plate of kreplach/krepl (“boiled pasta/dumpling”)? There is a good chance that his nickname would have been Kreppel. Perhaps that was the origin of the family name of Jonas Kreppel (1874-1940), a Yiddish German author and journalist born in Drohobycz, Eastern Galicia, who died of exhaustion after two years of forced labor in the Nazi concentration camp at Buchenwald.

Last names derived from food and drink could have been either occupational or personal. While more often related to a person’s occupation, in some cases they may have referred to a person’s physical characteristics or mannerisms.

When Jews were compelled to adopt family names in the early 19th century, it was only natural for these extant nicknames to turn into fixed hereditary family names. These surnames offer insight into everyday life in the historical Jewish communities of Central and Eastern Europe.