This week marks the 103rd anniversary of the lynching of Leo Frank, a Jewish industrialist who was falsely accused of a terrible crime and whose violent murder shook American Jews’ sense of security in their new home.

Frank was born in Paris, Texas but his family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where he grew up. He eventually joined the family business working for the National Pencil Company. In 1907 Frank moved from New York to Georgia after he was promoted to co-owner and superintendent of the company’s factory in Atlanta.

At the turn of the 20th century Atlanta was home to the largest Jewish community in the southern United States. Atlanta’s Jews were eager to integrate into the economic, social, and political life of the city, but also established a number of Jewish institutions. Although antisemitism was not a major issue, there was an awareness that they were somewhat separate from mainstream Atlanta society. Nonetheless, generally speaking the Jews of Atlanta felt secure in the city, and a sense of confidence about their place in society.

Frank became active in Atlanta’s Jewish community shortly after his arrival. In 1910 he married Lucille Selig, the daughter of wealthy Jewish industrialists. He also joined The Temple, the oldest Jewish institution in Atlanta, and was elected president of the Atlanta chapter of B’nai B’rith in 1912.

For Frank, this was a time of promise. But for many in Atlanta, this period was one filled with economic uncertainty and social insecurity. For Atlanta, this was a time of transition, when the economy was in the process of shifting from one based on agriculture to industry. Because of this change, many people abandoned their traditional work as farmers and began arriving in Atlanta, often working long hours in factories for little pay. The new economic reality also caused a social shift; men were no longer able to be the sole providers for their families, and women and children were increasingly entering the workforce. This new situation left men feeling emasculated, and worried about the moral corruption that might take place in factories with men and women working together.

The social, economic, and religious tensions that had existed under the surface would explode after April 26, 1913. That day, thirteen-year old Mary Phagan, the daughter of tenant farmers who moved to Atlanta in order to take advantage of the city’s economic opportunities, stopped by the factory in order to pick up a check for the work she had done that week. According to Frank, he paid Phagan and she left. Then, in the middle of the night, Phagan’s body was found by the night watchman in the factory basement.

Though the night watchman initially fell under suspicion, Frank quickly became a person of interest in the case. The police noted that he seemed nervous when they took him to the factory to see the body. Frank had also called the night watchman at least once on the night of the murder, something he had never done before. Additionally, several of the factory’s employees began telling investigators that Frank “indulged in familiarities with the women in his employ.”

The police were also under quite a bit of pressure to find and convict the killer quickly. A number of murders had taken place in Atlanta during the previous months. The city was on edge and frustrated with the police force, which seemed unable to catch the killer. As a result, the police had a vested interest in moving quickly to put together whatever clues they could in order to prove that Frank was the killer. The prosecutor in the case, Hugh Dorsey, was also convinced of Frank’s guilt—and had higher political aspirations that motivated him to aggressively push for a conviction (in 1916 he would be elected governor of Georgia). Dorsey’s case revolved around the testimony of the factory’s janitor, Jim Conley. Conley had signed four different affidavits, each of which told a different story regarding what happened the day of the murder. Conley was extensively coached by Dorsey so that he would stick to one story, and so that his testimony would be seen as reliable, and testified that Frank called him to his office, confessed to the murder, paid him to dispose of the body, and dictated a murder note.

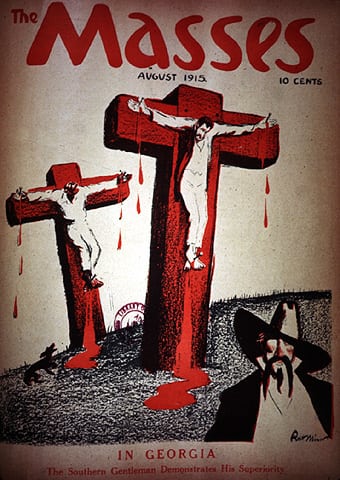

The trial began on July 28, 1913. Emotions ran high, and the atmosphere was one of anger and intimidation. Large and angry mobs inside the courtroom and standing outside chanted “Hang the Jew!” To many, Frank represented a way of fighting back against the changes taking place in Atlanta. In their eyes, Frank was a northerner, an industrialist, and a Jew who was imposing a new way of life on the south and preying on good southern Gentile girls. As one editorial put it: “When are the Northern Jews going to Let Up on Their Insane Attempt to Bulldoze the State of Georgia? WOMANHOOD MUST BE, AND SHALL BE PROTECTED; and we mean to have that understood by lascivious young Jews.” After less than four hours of debate, the jury found Frank guilty, and he was sentenced to death.

Frank’s execution was postponed as Frank and his lawyers worked on appealing his conviction. During this time, many of the witnesses who claimed that Frank had acted inappropriately with the factory’s women recanted their testimony. Evidence increasingly began pointing to Conley as the killer, and during the appeals process Conley’s lawyer told the trial judge that Conley had even confessed to the murder. Frank’s final appeal was to Governor John Slaton, who for nearly two weeks painstakingly went over all of the evidence. Eventually, on June 21, 1915 Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence to life imprisonment, stating “had I done otherwise, I would have felt like an assassin. As it was, I went six nights without sleep, but I would rather lose a few nights’ sleep than go forty years—if I live that long—with the blood of that man on my hands.”

This proved to be a deeply unpopular decision. Riots broke out and mobs vandalized Jewish homes and stores. Slaton received death threats; his term ended shortly thereafter, and he and his wife left the state for ten years. An inmate in the prison where Frank was being held slit Frank’s throat.

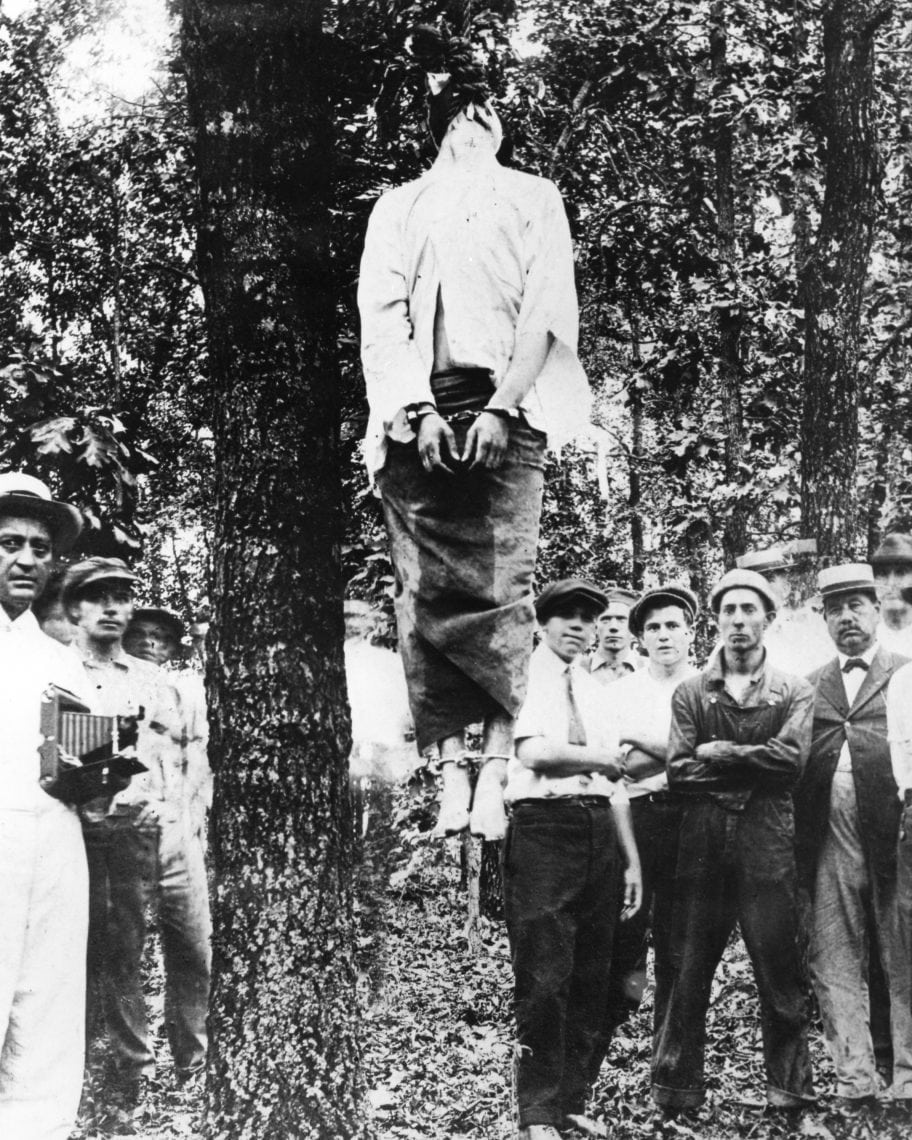

On the night of August 16, 1915 a group of 25 men drove to the prison where Frank was recovering from the attack. They overpowered the guards, cut the phone lines, drained the gas from the police cars, and abducted Frank from the prison. Throughout the ride to Marietta Georgia, Phagan’s hometown, the men attempted to get Frank to confess. Instead, he simply requested that his wedding ring be sent back to his wife. At dawn the vigilantes hanged Frank, pointing him towards Phagan’s house. Although the locals knew who had carried out the lynching, none of those who were responsible were ever prosecuted. They began referring to themselves as the “Knights of Mary Phagan,” and a month after the lynching they gathered on Stone Mountain and revived the Ku Klux Klan.

The lynching of Leo Frank deeply shook the Jews of Atlanta, and American Jews as a whole. Southern Jews began retreating from public life. The sense of security that Jewish Americans felt, that they were no longer in the old country where they had to worry about pogroms, was shattered. Frank’s murder was the catalyst for the establishment of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), an organization dedicated to fighting antisemitism and other forms of hate.

Most historians agree that Frank was innocent. In 1982, eighty-three-year-old Alonzo Mann testified that as a boy, when he was working in Frank’s factory, he witnessed Jim Conley carrying Mary Phagan’s body to the factory’s basement, but he did not say anything at the time because Conley threatened to kill him if he told anyone what he saw. In 1986 the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles issued Frank a pardon. It was not an exoneration, but it did acknowledge the state’s failure to protect Frank, thereby denying him the possibility of continuing to appeal his conviction, and it conceded the state’s failure to bring Frank’s killers to justice.

On August 23, 2018 a ceremony was held to rededicate the Georgia Historical Society marker that commemorates Leo Frank’s hanging. Justice may not have been served, but Leo Frank, and what his trial and murder meant to American Jewry, has not been forgotten among those who continue to fight against antisemitism, racism, and hatred.