While riding in a taxi for many long hours, en route from Russia to his city of birth, Benjamin Zar dropped the bombshell: “When we get to Mashhad,” he told Sarah, the woman he recently got engaged to, “my mother will give you a pendant that you have to wear. Otherwise, our lives will be in danger.”

That episode took place in the 1920’s. A few months earlier, Benjamin’s father, a fur trader from Mashhad, Iran whose name was Yaakov Zar, was hosted by the Jewish community in the Russian city of Mur (which can no longer be found on the map) where he had come on business. After Friday night services, Yaakov spotted an attractive girl named Sarah and decided to ask for her hand for his son, Benjamin.

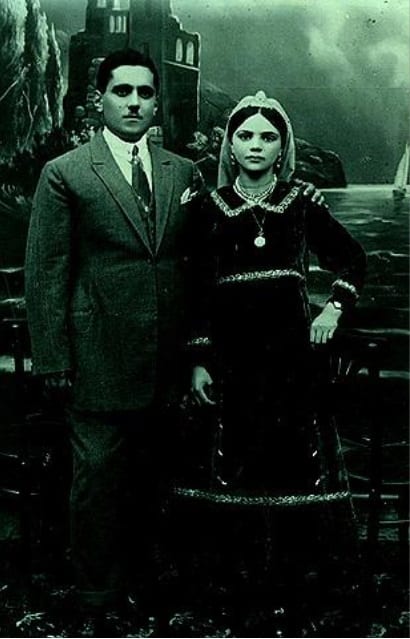

Following a brief acquaintance, Benjamin and Sarah got engaged. But Sarah had one condition for her prospective husband – that he take her to what she called “built Jerusalem.” Benjamin agreed to that condition, but asked that they first make a stop at his parents’ home in Mashhad and hold their wedding there.

Yaakov Zar, who was one of the wealthiest Jews in Mashhad, paid for the couple to come from Russia to Mashhad by taxi. During their trip, which lasted several days, Benjamin revealed the big secret of the Mashhad Jewish community to Sarah.

We now go back nearly 100 years in time. The place is Mashhad. The date is 12 Nissan 5599 (1839), just two days before Seder night. As fate had it, on that very same day the Shiites in Mashhad marked the Ashura” – the beheading of Iman Hussein, who was the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad and the son of Ali, the founder of Shia Islam – one of the two main branches of the Islamic religion.

And in the meantime, while Muslim believers were flocking to their mosques to commemorate this holy day, a woman from the Jewish community approached a Persian medicine man and asked him to cure the leprosy that had spread to her hand. In line with the advice of the medicine man who had instructed her to soak her hand in the blood of a dog, the woman asked a local Muslim boy to kill a dog for her. After doing so, an argument broke out between the boy and the woman over the amount of his fee. Following the dispute over the money, the enraged boy began running around the streets of the city, yelling at the top of his lungs that the Jews had killed a dog and named him “Hussein.”

Now try and visualize the picture. Thousands of Muslims are observing the Ta’zieh ceremony in the mosques, which includes self-flagellation and bloodletting to commemorate the suffering of their holy one, Hussein. And at the height of this ecstatic ritual, they hear that the dhimmi, who were residents of inferior status – and in this case the Jews – had dared to disrespect one of the holiest Muslims by naming a dog Hussein.

The results were devastating. An incited Muslim crowd attacked the Jewish neighborhood in the city and committed acts of looting, murder and rape. After 32 Jews were murdered, the entire community was forced to convert to Islam in order to save their children. Like the converted Jews in Spain, who were known as Cristianos Nuevos (New Christians), the Jews of Mashhad who converted to Islam were referred to as Jadid al-Islam (New Muslims).

The similarity with the conversos in Spain did not end there. Just like their brethren in the West, the Jews of Mashhad had no intention of abandoning the faith of their forefathers, which meant that they had to observe their Judaism behind closed doors. For 120 years, they led double lives – they were Jews at home and Muslims outside the home.

The main heroes of these camouflage tactics were actually heroines – the female members of the Mashhadi Jewish community. When posing as Muslim women, they had to wear the traditional female garment – the chador. Furthermore, because the local Muslim men were forbidden from looking at them, the Jewish women could clandestinely serve as couriers, concealing various items needed by the community under their chadors, such as Torah scrolls, phylacteries, prayer shawls and other ceremonial objects.

To avoid arousing suspicion, the Mashhadi Jews would buy food at Muslim-owned stores, but would later toss it out for the cats and dogs to eat. The slaughter of animals according to kosher dietary laws was carried out in secret, with the women delivering the meat to Jewish homes after hiding it under their chadors. During Passover, the Mashhadi Jews continued to bake bread, but burned it in ovens they built near the doors to their homes so the leavened bread would remain outside. Matzos were secretly baked in Jewish homes after midnight when the children were asleep. That way, if they were questioned by Shia fanatics, which was a common occurrence, the children would not have anything to divulge.

The Marranos of Mashhad set up synagogues in private homes and mikvehs – ritual baths – in basements. Every member of the community was given two names, one Jewish and one Muslim. And when girls were born, their ears were pierced and they were betrothed to boys from the community at a young age. That way, if Muslims came to ask for their hand when they grew up, they would be told that the girls were already engaged. Wedding ceremonies included a Jewish ketubah and a Muslim marriage certificate.

On Fridays, the Mashhadi Jews would go to the mosques, but would say kiddush – the Jewish blessing over the wine – as soon as they got home. They would open their shops on Shabbat (Saturday), but made sure to leave a child there whose job was to tell the Muslims that “papa will be back very soon.” That would continue until the last Muslim customers would lose their patience and go to another shop instead. That is how the Jews in Mashhad lived for 120 years. They were like human chameleons who changed their identities during the day and at night, on Shabbat and on holidays, at home and on the street, hoping that the day would come when they would be able to live freely as Jews.

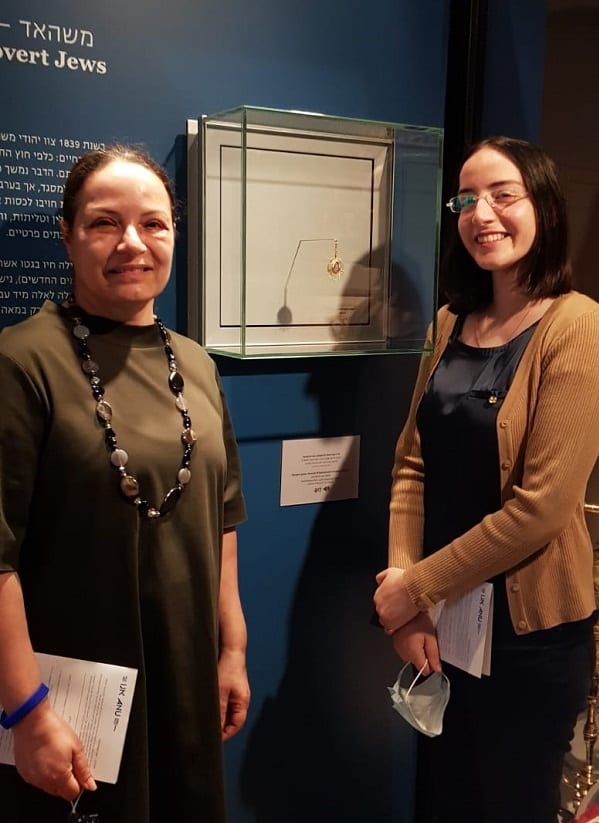

“And what about the pendant? Why do I have to wear it?”, Sarah asked her future husband while riding in the taxi that was taking them to Mashhad. Benjamin told his fiancé that one of the ways in which the Jewish women would outwit the Muslims was by wearing a pendant with a portrait of Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad. They would wear the pendant whenever they left their homes, enabling them to blend in with their surroundings without arousing suspicion. After the taxi arrived in Mashhad, Sarah was in fact given a traditional female garment – a chador – by her mother-in-law, Rachel Zar, as well as a Fatima pendant that she made sure to wear whenever she would go outdoors.

In the early 1930’s, after leading a double life in Mashhad for about eighteen months, Benjamin and Sarah Zar continued their journey to the Land of Israel, taking a taxi this time as well. Benjamin fulfilled his wife’s dream and the couple made their home in built Jerusalem, where they started an impressive family dynasty. The pendant that Sarah wore while she was in Mashhad is on display at ANU – Museum of the Jewish People, which was rededicated earlier this month.