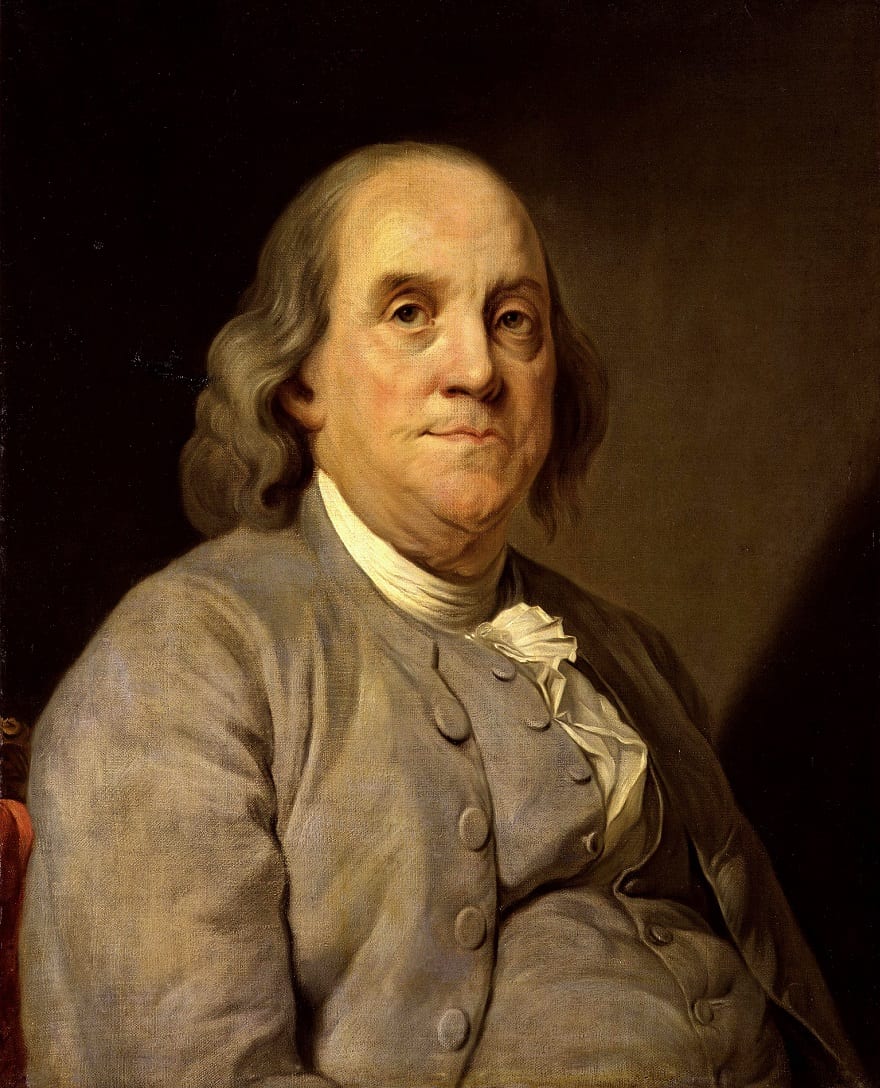

“Fart Proudly” (also titled “A Letter to a Royal Academy About Farting”, and in some cases “To the Royal Academy of Farting”) is an essay published in 1781 by Benjamin Franklin, who served as the American ambassador to France at the time, about the study of wind passing.

Franklin published the essay as a response to an invitation he had received from the Brussel’s Royal Academy. Resenting everything about the European academic sphere’s pomposity, pretentiousness, and narcissism, he composed a sarcastic work in which he suggested to specify funds for studying ways to improve the smell of human farts, in order to produce perfume for commercial use.

If you are not slightly familiar with Franklin’s biography you might take him for a rude fellow with a bit of humor. But that surely wasn’t the case. Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of America, is known for having dedicated his life to pursuing moral perfection, towards a methodical removal of all moral vices.

One of his techniques relied on a method he developed, called The Thirteen Virtues Chart, among which were sincerity and humility. He did not care for pompous scholars and upon encountering them he used a blunt sarcastic tone, hence the farts essay.

What we wish to do, however, is not to discuss wind passing, but rather to explain how The Thirteen Virtues Chart by Franklin evolved during the 19th century into a fascinating Jewish ethical movement called “Musar”, founded by rabbi Israel of Salant (Salanter) in eastern Europe.

Rabbi Israel of Salant, born in Zagare in north Lithuania in 1810, was a prodigy. At the age of 12, he went to study in the Salant yeshiva with rabbi Zvi Broide and soon made a reputation as a great Torah scholar. While in the yeshiva, he met rabbi Yoseph Zundel of Salant, who introduced him to the Jewish Musar doctrine – which changed his life.

A slight off-topic deviation is now in order:

The formal Jewish theology, represented by Chazal (our sages), perceived moral as a sphere completely detached from what occurs inside the human soul. They did not care whether the worshipper ponders over some mushrooms pizza while praying or wearing tefillin, as long as he performs the practice. “Greater is one who is commanded to do a mitzva and performs it than one who is not commanded to do a mitzva and performs it”, is considered one of the well-known rules in the Talmud, as well as Rava’s ruling in masekhet Rosh Hashana, that the commandments do not require any intent. Chazal’s ethics is all about one’s duties, rather than virtues and sincere intentions. They believed that the things we do automatically represent us far more than deeds that derive from the intent of the heart, therefore they focused on actions. The habit matters more than one’s feelings while practicing it. Chazal left the sphere of the internal soul to their main opponent – Christianity. In the words of Paul: Judaism represents Israel of the flesh, while Christianity represents Israel of the spirit.

The first work to challenge Chazal’s moral attitude and lift the curtain on the depths of the Jewish soul was the 11th century classic Duty of the Hearts by rabbi Bahya ben Joseph ibn Paquda in Muslim Spain. He was followed by Maimonides, that portrayed the doctrine of his own soul virtues in the preface to Masekhet Avot, and later on by Sefer Hahasidim in the Ashkenazi sphere. Then came Kabbalah and Hasidism, both of which focused on the inner spiritual religious experience.

Rabbi Israel of Salant, who lived in the 19th century, was the next link in this glorious chain of ideas. He was a unique innovator because while the other movements mentioned above investigated various realms, rabbi Israel of Salant focused on one goal: he dedicated his life to form a structured methodical moral doctrine, that appealed to the solid intellect and lucid mind. At first, he had a few disciples in Kovno, but within a few years, the small circle became a large movement. Various Jewish communities established a “house of ethical teachings” – Beit Musar, a unique kind of Beit Midras, in which they taught Musar books in particular. In the late 19th century the movement spread throughout eastern Europe. Rabbi Salanter’s ethic studies became a considerable component of the study routine of prominent yeshivot such as Slabodka, Mir, Radun, and Novardok.

At first, the new movement was gravely resented by the rabbinical authorities, partly due to rabbi Israel’s criticism on their exclusive focus on the Mishna and adjudicative literature, that took over the yeshivot, that became institutes of extremely sophisticated, ceaseless debating. Salanter claimed that debating for its own sake uproots the spirit out of religious life and makes Judaism nothing but a procedural system of dos and don’ts, lacking any spirit or inspiration. As a result, Salanter said, many sections in the Torah, dealing with moral virtues or interpersonal relations, were neglected for centuries.

Salanter feared not to borrow from non-Jewish sources and disciplines, such as the notion that one must reach the dark elements of his mind, an idea that resembles the concept of the subconscious, borrowed from Kategorischer Imperativ by Immanuel Kant. Another foreign influence was our acquaintance Benjamin Franklin, whose Thirteen Virtues Chart rabbi Israel of Salant read in the book by the Jewish maskil, Mendel Lefin “Cheshbon Ha-Nefesh (moral reckoning). Rabbi Israel was affected by the moral method of Franklin and introduced it as a central teaching tool in his Musar institutes.

We started with pride, let us conclude with pride as well. According to rabbi Israel of Salant, pride is man’s greatest enemy. “When I see a proud man I feel nauseous”, he used to say. Founder of the Musar movement told his disciples, again and again, that pride is the hardest vice to mend. Unlike Franklin’s strategies upon meeting with proud people, rabbi Israel used to hold special practices in the month of Elul, to drop the ego, which he thought was holding humans back from going through a genuine self-reckoning before the Day of Atonement.

Happy Holidays!