Nessim Joseph Dawood, who translated the Quran into English in the middle of the 20th century, was not, of course, the first to translate the Holy Book of Islam into English. But he is responsible for its most widely read and popular translation. Interestingly enough, one of the people who deserves the most credit for introducing Islamic culture to the West was a Jew.

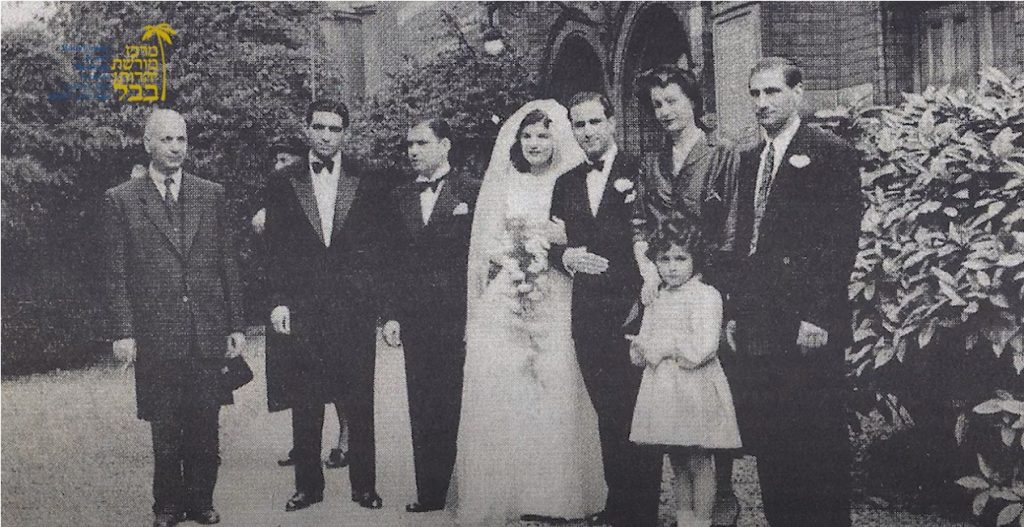

The Jew in question was born in Baghdad, Iraq to the Yehuda family – a longstanding and highly respected Jewish family that left the Land of Israel prior to the destruction of the First Temple. However, his name on official documents was Nessim Joseph David. When he moved to London, he changed his last name David to its Arabic form, Dawood. He later used the pen name of N.J. Dawood.

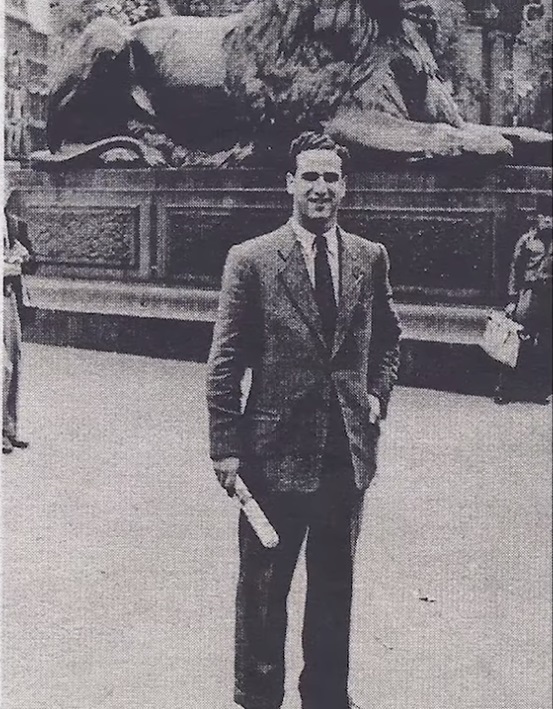

From a young age, Dawood was an English literature enthusiast and an avid admirer of the writings of William Shakespeare, whom he remained faithful to until his dying day. When still a high school student in Baghdad, he started working as an English to Arabic translator for some Iraqi newspapers. Whereas most of his family members emigrated at some point to Israel, the 17-year-old Dawood chose to go to London and pursue his studies overseas. He arrived in England in 1945, equipped with an Iraqi state scholarship to London University. Because the campus had been evacuated from London during World War II, he actually attended university in Exeter in southwest England, where he earned a dual Bachelor’s Degree in English Literature and in Arabic.

Based on the degrees he obtained, it appears that although Dawood had decided to remain in England, he never abandoned his mother tongue. On the contrary. He delved into Arabic more and more. Dawood was a proud Jew who loved Arabic literature with all his heart. He also clung to memories of the days when Jews and Muslims in Iraq lived together in harmony. “As I see it, he was a bridge between Arabs and Jews and introduced the charm of Arabic literature to the West,” said his relative Rachel Khalaschi, in an interview she gave to the Babylonian Jewry Heritage Center. “It was his life’s calling.”

After graduating from university, Dawood initially worked as a journalist and teacher in London, but then went back to translating – and this time from Arabic to English. He would end up devoting his life to disseminating the treasures of Arabic literature to the West. It all happened quite quickly, and his first major achievement came at the age of 27, when the British publishing house, Penguin Books, published his translation of The Thousand and One Nights (also called The Arabian Nights). That collection of Middle Eastern folktales, which supposedly had been told to King Shahryar by Scheherazade over the course of 1,001 nights in order to put off her execution, was first translated into English at the beginning of the 18th century. It soon gained popularity and was translated again several times after that.

What made Dawood’s translation special is how he made the text readable after doing away with the archaic wording and replacing it with contemporary, coherent and comprehensible language. Later on, Dawood also adapted some of the tales in the anthology, such as Sindbad the Sailor and Aladdin and the Enchanted Lamp, for children.

Following the success of Dawood’s translation of The Thousand and One Nights, Penguin Books signed a contract with him for a new translation of the Quran – the project for which Dawood will be remembered forever. There are conflicting accounts of who conceived the idea of publishing a modern translation of the Quran. According to one account, E.V. Rieu. the editor of the Penguin Classics series, and Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin Books, were the ones who approached Dawood. However, in an interview he gave in 1990 to the literary magazine, Bookseller, Dawood claimed that he came up with the idea, and even had to convince the two Penguin executives that there were enough people who would want to read the Quran in English. In retrospect, he was right: Dawood’s translation became the best-selling English translation of the Quran, and to date it has been reprinted over 70 times.

Just like in the case of The Thousand and One Nights, Dawood wanted to translate the Quran into contemporary and readable English – something which had never been done before and could have been considered scandalous. Translations of the Quran have always been problematic in Islamic theology. The conservatives view the Quran as a holy text that cannot be replicated, and because it was given to Muhammad from above, it cannot be translated. Furthermore, in Semitic languages, words can have different, context-dependent meanings, which makes them even more difficult to translate. That is why many people regard the translations of the Quran as being solely interpretations, and not the text itself.

Nonetheless, the Quran has, of course, been translated into many languages. The first time it was translated into English was in the 17th century. But it was not from the original Arabic, but rather from a French translation. The first time that the Quran was translated into English from the original Arabic was in the 18th century, and then it was from the perspective of Christian missionaries. It goes without saying that over the years the Quran has been translated into English by Muslims as well.

Nessim Dawood’s son, Dr. Richard Dawood, believes that his father was not driven by any political or religious agenda when he translated the Quran. What interested him was the language and how to make the Holy Book of Islam readable and comprehensible to the general public, and by doing so preserve the beauty of the text.

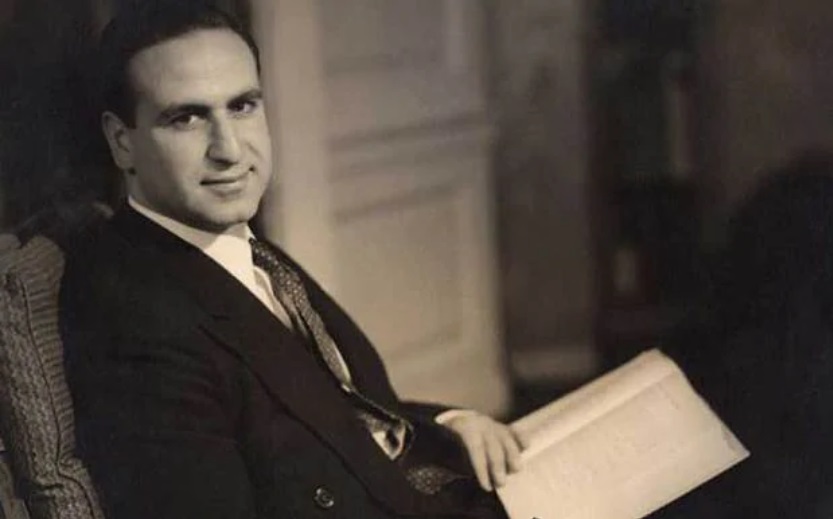

Dawood treated the Quran as if it were a work of literature, and its translation became his life project. His translation was first published in 1956, but many of the later reprints also included his own re-editing. Everyone who knew Dawood said that he was a perfectionist, and during his lifetime he updated the text numerous times, while revising and improving his choice of words over and over again. Some say that he didn’t stop until the day of his death.

In an interview he gave to the Jerusalem Post after his father’s death, Richard said the following: “My father never had any other agenda than the agenda of a linguist. He began his project at the age of 27 and finished it at the age of 86, when he carried out his last revision. In fact, he was still looking at the Quran shortly before he died. He was always looking for a better way to express something, striving to make it as perfect as he could in order to reproduce the poetry accurately. ”

As noted above, Dawood was not the first to translate The Thousand and One Nights into English, nor was he the first to translate the Quran. But to a great extent, he can be credited with their popularity in the West. He was the one who brought them to readers who were deterred by the old-fashioned and obsolete translations. As might be expected, his contemporary translations annoyed the purists. Dawood was a translator and editor with a vision and confidence, who allowed himself to make changes to the original text and to delete and abridge certain wording. Not everyone viewed his approach favorably. But his many admirers maintain that his words were full of charm and liturgy, yet never heavy, archaic or incomprehensible.

“All other English translations are pompous, archaic and unreadable, except by the enthusiast,” wrote the British journalist, Philip Howard, in the Times in 1986, after new printings of Dawood’s translation of the Quran were published. “Despite the language barrier, Dawood captured the thunder and poetry of the original in such passages as those dealing with the Day of Judgement, and Heaven and Hell.”

After his first translation of the Quran was published, Dawood wanted to remain in academia and began studying for a PhD. But he was forced to abandon his plan in order to support his family. At the end of the 1950’s, he opened his own translation agency that specialized in Arabic, and in particular business translations. Many products that were being exported from the West to the Middle East received their name, product description, logo and promotional text thanks to Dawood. The list of his accomplishments in the business translation industry also included the Arabic words he invented for modern terms that did not have names in literary Arabic. For many years, his company also provided printing and dubbing services in Arabic, and Dawood himself dubbed quite a few texts in Arabic in his own voice.

As the leading translator of materials from Arabic into English and from English into Arabic in the 20th century, Dawood received another important editing task at the end of the 1960’s. Princeton University Press commissioned him to edit and abridge the Franz Rosenthal translation of The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. (Rosenthal, who was also a Jew, was born in Germany and became an expert on Arabic literature).

The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, which was written in the 14th century by the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun, is a seminal work in the field of historical research that interfaces with a large number of academic disciplines. Like in his past undertakings, Dawood’s editing of The Muqaddimah managed to make the text comprehensible to a new generation of English readers, among other things by reducing its original three volumes to just one.

Nessim Joseph Dawood died in London in 2014 at the age of 87. He was survived by his wife, three sons and nine grandchildren. He also left behind scores of people who owe their love for the canon of Arabic literature to him, as well as English-speaking Muslims who were born in the West and are now able, thanks to Dawood, to understand and connect with the sacred texts of their faith.