In Jungian terms, Israel’s sweeping victory in 1967 symbolized an archetypal revolution of the common Jew. The archetypal passive, docile, and persecuted Diaspora “galut Jew” – whom Bialik slammed in his poem “City of Slaughter” in 1903 – morphed into that of the brave, heroic, flawless “Jewish soldier” who destroyed his mortal enemy in six days of pure courage. The liberation of the Kotel provided a cathedral. It was not just the concrete liberation of the Jewish People’s holiest site – it was the spiritual and absolutely final liberation of the “galut Jew’s” flaccidity.

The revolution of awareness began with the establishment of the Bar Giora organization in 1907; continued with the Hagana and the Jewish Underground in 1948 and the Sinai Campaign (Kadesh Operation) in 1956; and was completed in the nationalist crescendo of the Six-Day War. That created an emotional sound box that resonated not just among the Israelis who faced a real existential crisis in 1967 – but throughout the Jewish world. Among American, French, British, and Soviet Jews. They were all on a Messianic-Zionist wavelength that had not been seen since the Biblical Kingdom of Israel.

But the circumstances of Jews in the former Soviet Union were unique. Unlike Jews in the free world, they were behind the Iron Curtain in the domain of a Soviet world power that supported and armed the Arab armies, and worked indirectly to destroy the State of Israel. The question of their dual, civic loyalty – the lot of every Jew living in the Diaspora – was in their case running on high octane. Add to that the daily threat of the secret police and a generally Orwellian atmosphere. That nearly made being a Zionist Jew in Russia into an oxymoron. That may be why “Operation Wedding” – the attempt to smuggle a group of adventurous Zionists out of the Soviet Union – is considered one of the most heroic events in the struggle to free Soviet Jewry.

Mark Dymshits, born in 1927 in a small town near Kharkhiv, Ukraine, was the son of a typical Jewish family that had been successfully “re-educated” by the Soviet regime’s institutions. He suffered a personal tragedy in World War II, when both his parents died in the German siege on Leningrad. The family trauma and his identification with the Soviet cause led Dymshits to enlist on the appointed day in air force training and serve as a combat pilot in the Red Army. Upon his discharge as a major in 1960, he went to work as a pilot for a small airline in Bukhara.

Like many Soviet Jews, news of Israel’s stunning victory against the Arab armies in the Six-Day War, anti-Semitism, and the anti-Zionist propaganda campaign of a government that supported those armies during the war – ignited a Zionist flame in Mark’s heart and a yearning to make aliyah. But in those days, the chance of obtaining a permit to emigrate to Israel was equal to that of singing the Star-Spangled Banner in central Moscow without being shot in the head.

Mark lived in the Diaspora, but he was not a “galut Jew.” He hatched a daring, revolutionary, and creative plot to skyjack a plane in Leningrad and fly it to Sweden. His search for partners led to Hillel Butman, an operative in Leningrad’s Zionist underground cell. The two of them formulated a plan in which the plane’s passengers would be Zionist Jews who sought to make aliya. Their cover story was that they were traveling to a large family wedding in Stockholm (hence the name of the operation). They decided to take control of the cockpit without arms to avoid harming the pilots. If the pilots refused to collaborate in flying to Sweden, Dymshits planned to fly the plane himself.

Dymshits and Butman presented their daring plan to the cell in Leningrad. The initial excitement of the cell’s members gave way to fear that the operation’s failure could put an end to the Zionist movement in the USSR. When they could not achieve a consensus regarding the plan, they decided to present a query to the Israeli government. They did so during the Pesach holidays and whether coincidentally or not (you decide), a Norwegian Jew named “Rami” entered Leningrad’s synagogue. The cell’s members sent the following question with Rami: What is the Israeli government’s opinion of the skyjacking plan? The message was conveyed via the Israeli Embassy in Oslo to Golda Meir’s Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem. The Israeli government’s response was negative. Members of the committee in Leningrad received a telephoned message that “The professor who is the leading medical authority does not recommend the use of the medication.” That categorical reply caused the people in Leningrad to drop the plan.

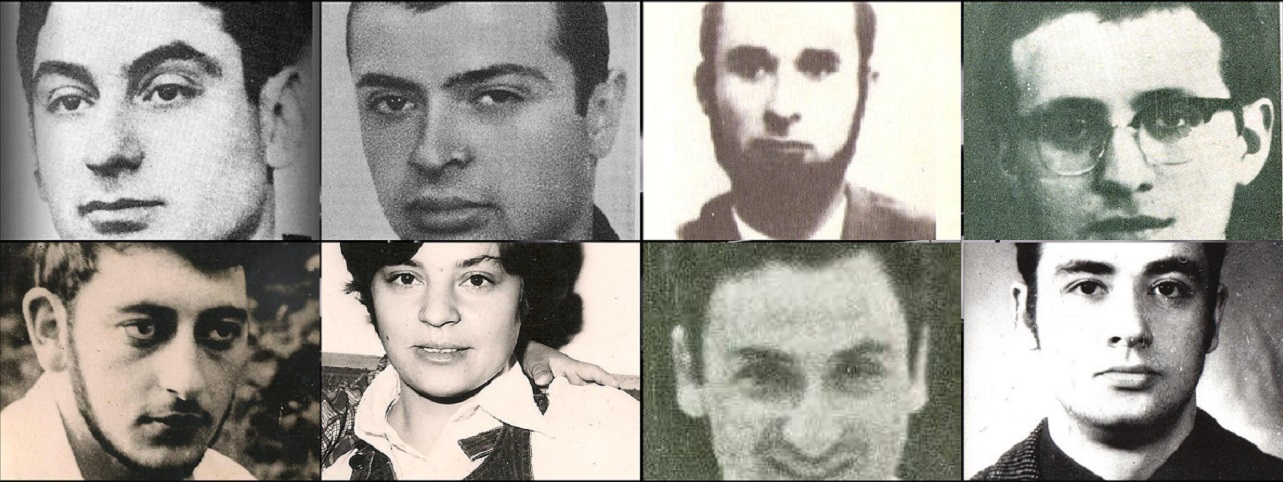

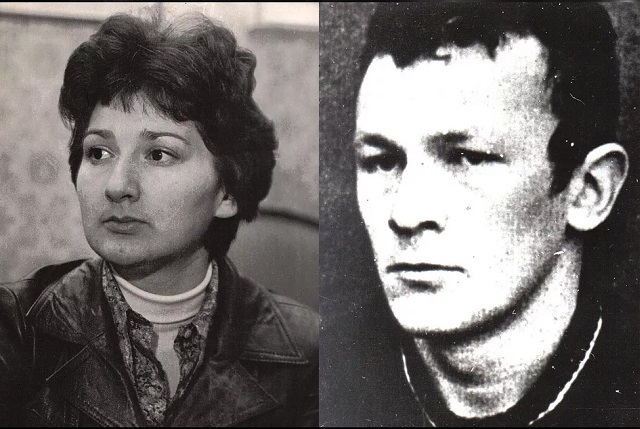

But Dymshits was not assuaged and despite the Israeli government’s objections, he turned to a Zionist cell in Riga who agreed to collaborate with him. He shared his secret plan with Sylva Zalmanson, her husband and freedom-fighter Edouard Kuznetsov – who had already served seven years in prison for anti-Soviet propaganda – Sylva’s brothers Wolf Zalmanson and Israel Zalmanson, their friend Yosef Mendelevich, Arie Hanoch, Mendelevich’s brother-in-law and his wife Mary, and Dymshits’s family – his wife Ella and two daughters Yulia (age 15) and Lisa (age 19).

The 12 members of the group arrived at Smolny Airport near Leningrad at dawn on June 15, 1970. They soon discovered that they were being followed, but decided anyway to walk toward “the noose,” as Hillel Butman called it in his book “From Leningrad to Jerusalem” – rather than away from it. A few steps before boarding the plane, Dymshits and friends were arrested by the KGB, who it turns out had known about the plan for months.

Leningrad Trial I, as the trial of the group’s members was called, began on December 15, 1970. The defendants were charged with high treason. Some of them were sentenced to prison and Dymshits and Kuznetsov were sentenced to death. Their sentence was reduced from death to imprisonment in response to international protest, and Dymshits was released in a prisoner exchange after serving nine years. When his plane for Israel took off in New York, the crowd applauded him.

Dymshits worked in Israel’s military industry for seven and a half years before taking early retirement. He spent his last years painting in Rehovot. Dymshits died four years ago and was laid to rest next to his wife Ella.

It is worth telling at Pesach his tale and that of his friends, anonymous heroes and freedom fighters, who breached the Iron Curtain to pave the way for the future great waves of immigration of Jews from the former Soviet Union.