In 2014, I went to Bosnia to do a story on the rescue of the Sarajevo Haggadah, which is one of the oldest Jewish books in the world. It was rescued by Muslim curators in two different wars – in the Second World War and in the war in the Balkans. The story was told to me by Enver Imamovic, who salvaged the Haggadah in the 1990’s. According to him, in World War II the librarian, Dr. Dervis Korkut, rescued it from the clutches of the Nazi criminal, Johann Hans Fortner, who was sent to Sarajevo to seize the Haggadah and add it to a collection of Judaica that the Nazis were assembling in Prague. Korkut hid the Haggadah in the mountains, where it remained until the Nazis were defeated.

This is not a fabrication – Korkut was recognized by Yad Vashem as being a righteous among the nations also for rescuing a Jewish girl. Eli Tauber, one of the heads of the Jewish community in Sarajevo, verified the story. Korkut even complained that although the Haggadah had been saved, Fortner did manage to steal the official records of the community, erasing its detailed history dating back hundreds of years.

Apparently, the collection that the Haggadah was supposed to become part of is the Jewish Museum of Prague, which was established in 1906 and today is a popular site that draws Jewish and non-Jewish visitors alike. But according to one of the theories, after winning the war and achieving their overarching goal of annihilating the Jewish people in Europe, the Nazis intended to open a museum that would commit a second genocide and depict the Jews as a people who had to be exterminated because they were a decadent and parasitical race. That was why the Nazis were holding onto a centuries-old collection of Jewish artifacts in Prague. Those efforts were part of the work done by the Institute for Research on the Jewish Question, which was engaged in finding alleged scientific justification for wiping out the Jews.

The existence of that theory also has a connection with a roving exhibition in the United States that opened in 1983. A certain warming of the relations between the West and communist Czechoslovakia led to that roving exhibition, which was organized by the Smithsonian Institution and featured around 400 items from the collection in Prague. In an article in the New York Times, the exhibition was said to be so valuable that it was brought to the United States on a U.S. Air Force plane.

The director of the exhibition, Anna Cohn, told the newspaper that the original collection had been assembled by eight Jewish curators who were inmates in the Terezin concentration camp. All but one of them were murdered before they had a chance to complete their work. One of the driving forces behind the roving exhibition describes those Jewish intellectuals a bit strangely. “They were very brave people who knew they could not save people, but worked hard to preserve the heritage that was dear to them.” Displayed in a sensitive and symbolic manner, the exhibition also included drawings by children made in Terezin.

But the problem in the story is the lack of any credible proof of the theory. No evidence has been found in Nazi records that they intended to open such a museum. Having said that, when in 1942 the Germans seized the Jewish Museum in Prague, it only had 760 artifacts. After that, as a result of the Nazis’ concerted efforts, more than 140,000 artifacts were collected from synagogues throughout Czechoslovakia and Central Europe. Nonetheless, Nazi records that clearly attest to the intention to open such a museum – simply do not exist. In fact, the Jewish Museum in Prague has also expressed some reservations. A more prevalent logical explanation pinned the theory about the Nazis wanting to open a museum on their inclination to record and catalogue all of their operations, coupled with an economic interest to appraise the value of the items they had confiscated from their owners.

Even though the Jewish Museum and the Jewish community were under the control of the Nazis’ Central Agency for Jewish Emigration, most of the planning and organization regarding the collection of the artifacts was carried out by the Jewish community itself, and in particular by the founder and curator of the Jewish Museum in Prague, Salomon Hugo Lieben, and the curator of the Jewish Museum in Mikulov, Alfred Engel. Some claim that the Nazis’ willingness to allow the museums to continue doing their work had to with their future plan to open a museum for an extinct race after the war.

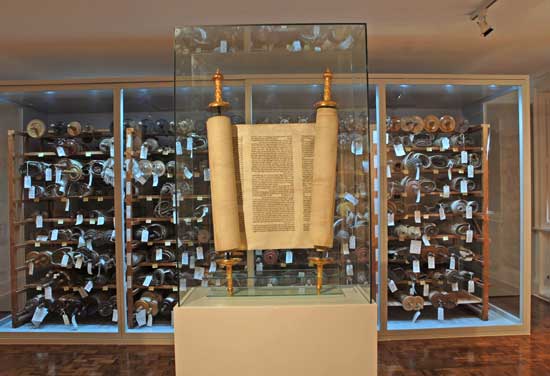

On August 3, 1942, a call went out from the Jewish Museum in Prague to the Jewish communities in the countries under the German protectorate, instructing them to send all the items from their synagogues to Prague, including ritual objects, books and archived materials. The museum staff knew they were entrusted with preserving the remnants of Jewish life and were extremely cautious in their contacts with the Nazi authorities, hoping to be allowed to continue their work. Thanks to their diligent and delicate work, the staff at the Jewish Museum in Prague managed to undermine the full extent of the Nazi looting of Jewish property and some of the treasures were transferred to safe havens, rescuing Jewish history.

The museum staff may have managed to salvage the remnants of Jewish life in Bohemia and Moravia, but they were unable to save their own lives. All the Jews who took part in gathering the materials were deported and only two from the original group of curators survived – Hana Volkova and Dr. Karel Stein. Both of them returned to their jobs at the Jewish Museum after the war ended. Given all that happened, the work and feats of the museum staff were beyond imagination. All the deportations from Prague ended in February 1945 and there was no one left to run the museum. Prior to that, the staff had managed to collect artifacts from 136 former Jewish communities in Bohemia and Moravia. Those artifacts included 212,822 ritual objects, books and archived materials – including 1,564 Torah scrolls. Their work was so meticulous and thorough that the catalogue they prepared is still used today to accurately identify every object they collected.

In 2017, a Jewish-Australian musician by the name of Bram Presser embarked on a journey in search of his roots. His original contribution to Jewish culture was in the form of a heavy rock band that performed covers for Jewish songs from the soundtrack of Fiddler on the Roof, as well as “Jerusalem of Gold.” His grandfather was a Jewish scholar from Czechoslovakia who renounced his Judaism after the Holocaust. He later renewed his covenant with G-d and began observing the commandments again after his grandson Bram survived complicated cardiac surgery as a child.

After reading research published by Monash University, Bram discovered that his grandfather had translated the Passover Haggadah into Czech, and in 1942, after being deported to Terezin, he was one of the hundred or so scholars who were commanded by the Nazis to begin the painstaking process of sorting the objects and artifacts. Presser concluded that his grandfather had been one of the cataloguers in the Nazis’ project, which can substantiate the adamant theory that the Nazis planned on opening a museum and how it was connected with the Jewish Museum in Prague. Presser did not advance that hypothesis in the form of research, but rather wrote an excellent and prize-winning book entitled The Book of Dirt, part of which is nonfiction and part of which is fiction.

Another book that appeared in 2017 depicted the chosen scholars’ project of the Nazis in a somewhat different light. Anders Rydell, a Swedish author, published The Book Thieves, in which he writes that the Nazis looted libraries in all the places they occupied in Eastern Europe, as well as millions of books found in Soviet collections after their early victories over the Russians in the war. A Nazi criminal named Alfred Rosenberg was in charge of the organized theft of the books. When it came to the Jews, Rosenberg’s motives perhaps reflected an attempt to use the books as a means to uncover a global Jewish conspiracy.

In any event, the Germans were in possession of millions of Jewish books, and to sort them they located Jewish scholars who were prisoners in the camps and ghettos. The original sorting center was in the Vilna ghetto. Following their defeats in the east, the Nazis had to relocate those efforts closer to home – and the Terezin concentration camp was considered the most suitable. The cynical name they chose for the sorting unit they established was the “Talmud Commando.” Because Terezin was showcased to journalists and the Red Cross as a ‘model’ ghetto, pictures of librarians engaged in sorting books looked good and gave credence to the deception.

In his book, Rydell described the dilemmas faced by the Jewish librarians, both in Vilna and in Terezin. They were commanded to save books that could support Nazi research and theories, knowing full well that they were probably contributing to pseudo-research that would later justify the Holocaust. At the same time, they were forced to condemn other books to extinction. Rydell does not shy away from the similarity to the horrific decisions that some Jews had to make that impacted other human lives.

So, the Nazis collected, sorted and catalogued huge quantities of books and Jewish collections, with their intentions not being altogether clear from a historical perspective. But the text that you are now reading comes from a blog posted by ANU-The Museum of the Jewish People. The Holocaust is not its main focus – but rather the documentation of Jewish life, culture and energy over thousands of years. Maybe this is another victory over the Nazis. They not only sought to make Jewish women and men extinct, but also Jewish history, which they wanted to seize, exploit and distort for the needs of their vile racist theories. That, too, they failed to do. We are here.