“Though Rembrandt was not Jewish, we must consider him as “a Jew of honor”, for his love and empathy towards the Jews”, the national poet Bialik wrote in 1932, in a preface he contributed to the Jewish painter Leonid Pasternak’s book on the art of Rembrandt. Bialik also noted that “this gifted genius has miraculously grasped and seized the core of the Hebrew soul, like no other gentile painter has ever succeeded to do.”

Bialik was not the only admirer of the outstanding Dutch painter. He is the most mentioned artist in Hebrew literature, referred to in stories by Agnon; discussed as an inspirational figure by rabbi Kook; was the subject of poems by Schin Shalom; even the great author Ephraim Kishon used Rembrandt’s character in his satirical play Pull Out the Plug, the Water’s Boiling, a poignant satire on modern art, where Rembrandt was represented as the ultimate role model artist, unlike other petite pretenders of the 20th century.

So is there some elusive Jewish element in Rembrandt’s art, which made him such a wonder for key persons of the Hebrew culture? Why was he commemorated in the artists’ quarter in Tel Aviv, rather than, for example, Da Vinci, who has a negligible street after him by the Cameri theater, or Michelangelo, who was exiled out of Tel Aviv altogether, to Jaffa?

The Jews, being a battered degraded nation in exile, were always in want of some good old Hubris, therefore they tended to embrace geniuses who had not Jewish origins. Still the story of Rembrandt stands out, to the point that many actually insisted he was himself a Jew after all.

If we think of the 15th century as the century of the Spanish, and of the 18th century as French – then the 17th century undoubtedly belonged to the Dutch. The Dutch golden age was the result of unique circumstances that included prosperity – following the foundation of the Dutch East India Company, the first multinational corporation in history, that conquered the new world; the rise of a wealthy middle class of merchants and professionals; and a flow of immigrants from the Spanish low countries (today Belgium and Luxembourg) that brought a free protestant attitude, turning Amsterdam into a universal vibrant center of liberalism.

The 17th century was also the finest hour of the Jews of Amsterdam. Tens of thousands of them travelled there following their expulsion from Spain and Portugal, after centuries of severe identity issues, forced to act as catholic outdoors, and as Jewish indoors.

Amsterdam allowed them to rediscover and celebrate their Jewish identity. This exiting revelation led to a burst of and cultural prosperity and innovativeness. Numerous Hebrew printing houses were established, synagogues and religious institutes acted, while a middle Jewish class that led rich intellectual life thanks to their financial success was rising. The Jewish community was home of men such as Menashe Ben Israel, statesmen and founder of the first Jewish printing house; the outstanding preacher Issac Abuhab; the philosopher and famous heretic Spinoza; and the famous physician Efraim Bueno, to name just a few of the well-known Jews who lived in the “New Jerusalem”, as Amsterdam was then called.

Notably, all of these individuals were friends with one painter called Rembrandt. Ben Israel, Abuhab and Bueno, who was Rembrandt’s physician, even had their portrait painted by the brilliant master. In fact, Efraim Bueno’s portrait is considered to be one of Rembrandt’s greatest pieces.

In 1639, at the peak of his glory and wealth, Rembrandt bought a splendor three stories house in the Jodenbuurt, the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. Why would a Christian want to settle among the people who killed the savior? Perhaps this proves he was indeed a Jew? In fact, he bought the house when the place was still called Breestraat (broad street), as it was a central path in the city. It wasn’t until the 18th century, as Dr. Doron Lurie the art historian states, that street became the heart of the Jewish quarter. Only then did Breestraat became Juden Breestraat. Similarly, the couple painted in the famous “Jewish Bride” work was not Jewish, and the painting received its name years after painted.

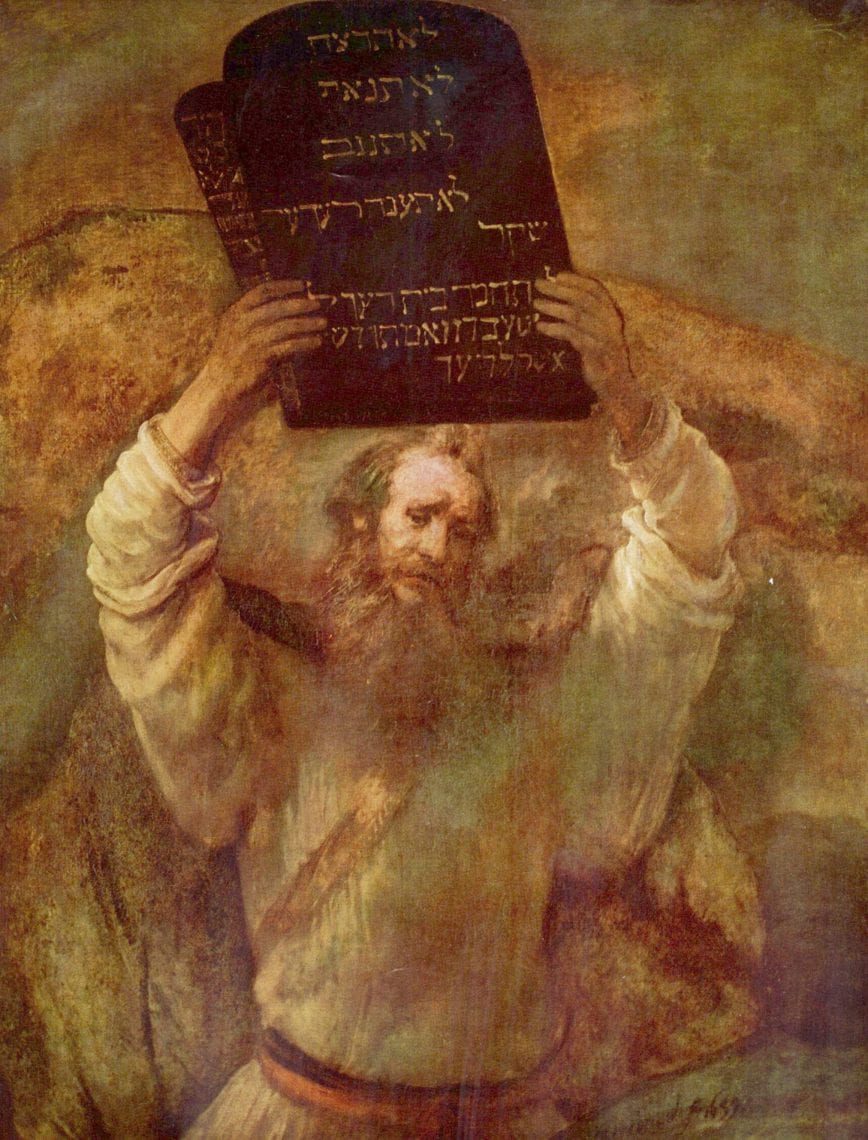

According to Dr. Lurie, the main reason for the affiliation between Rembrandt and the Jews of Amsterdam was his obsession with the bible. Like many other prominent artists of that protestant pro biblical period, he fell in love with the biblical stories and painted many biblical scenes, such as the Sacrifice of Isaac in 1635; Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law is a 1659; Belshazzar’s Feast; Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael; and of course the four famous portraits of Samson.

Rembrandt, who was obsessive with accurate details believed that his Jewish neighbors in Amsterdam were the authentic representatives of the ancient Hebrew nation. Many a time he used his friends as models for various biblical scenes. Rembrandt believed that if he placed an odd hat or headpiece he was able to create get the most reliable biblical kings and prophets.

Ironically, not only the Jews considered Rembrandt one of them, but also their harshest enemies. Hitler and Goering apparently collected all of Rembrandt’s portraits, intending to display them after the war was over as a bizarre exhibit of a degenerated, extinct nation.

Though apparently Rembrandt was not Jewish, since his death as a poor lonely man in 1669, the belief that he is “one of us” kept on occupying our imagination and sympathy, just like his wonderful art.

(Translated from Hebrew by Danna Paz Prins)