These European Jewish boys fled the Nazis to America, leaving parents, siblings, friends and the beloved continent that stabbed them in the back behind. They did not imagine in their wildest dreams that they would return to the scene of the crime as soldiers in the Allied Forces’ special corps.

No, this is not a trailer for Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds.” This is the story of “The Ritchie Boys”, Jewish refugees who arrived in America during the war and seized that once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to avenge the Nazi extermination machine that killed their families and so many members of their People.

Fred Howard and Guy Stern remember to this day the moment in which they entered the gates of Camp Richie, a secret intelligence facility in the heart of the Maryland foothills. The two of them said in the 2004 documentary “The Richie Boys” that it was “as close as you could get to the Tower of Babel. you could hear European languages – German, Polish, French, Yiddish and Italian – wherever you turned.”

Howard and Stern, who immigrated to the US alone when they were in their 20s, did lose their mothers, but not their mother tongues. That was why they were drafted into the intelligence unit’s special ops. Or as Howard put it, “You can train anyone to shoot a gun and charge in six months. It takes a little more time to teach him a new language.”

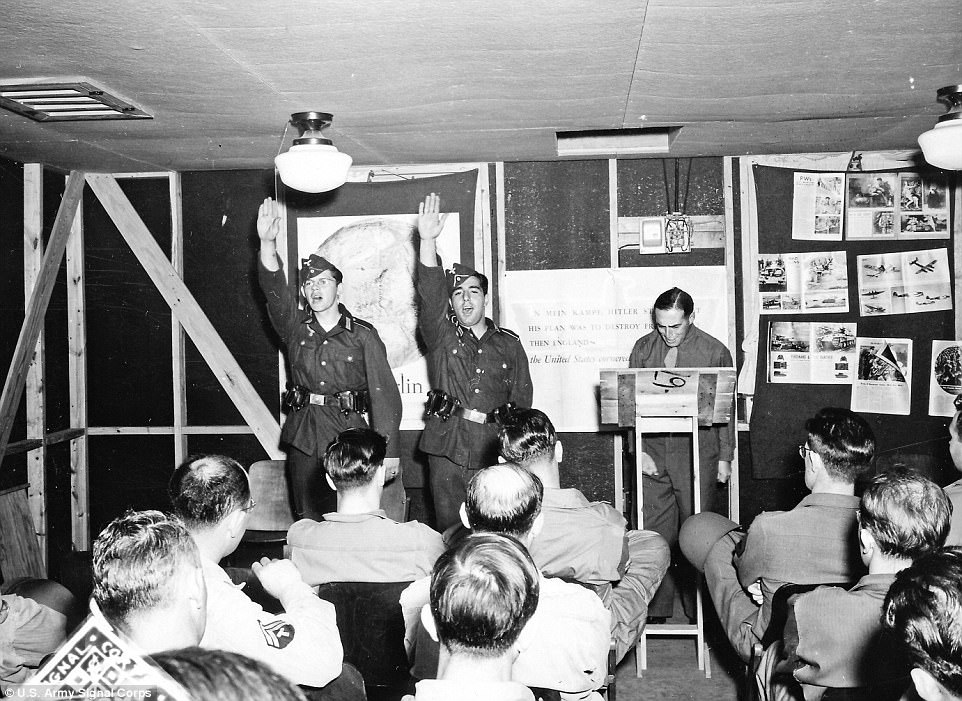

The American War Department needed soldiers who spoke European languages for its missions across enemy lines. But soldiers who merely spoke a foreign language did not make the cut – the department meticulously cherry-picked these soldiers. Inventiveness, sophistication, a cool head, and flexibility in complex situations were all required of candidates who would one day don German officers’ and soldiers’ uniforms to plant disinformation among enemy ranks.

Camp Richie maintained an intensive schedule. These soldiers spent several months training in psychological warfare, cracking Morse code, photographing from the air, uncovering the German army’s knowledge of warfare, becoming adept at interrogating German prisoners of war, and learning to kill as swiftly as possible in dangerous circumstances.

Howard fled to the US in 1938. His parents received one immigration permit from American authorities and immediately handed it to their only son. They never saw him again. Most of those interviewed in the documentary tell similar stories. Jewish refugees alone in a strange land, filled with gratitude to the land that fulfilled their basic human need: To belong to something bigger than themselves and contribute to the free world’s joint effort to quash the Nazi forces of evil.

“As long as we were training, everything was easy,” the two of them recall, waxing nostalgic. “There was a special feeling in the camp. A sort of Jewish shtetl. Here I am with a busy social life and feelings of national pride.” The move to real warfare took place in May 1944, when the officers gathered the teens in one of the camp’s main buildings and ordered them to prepare for D-Day.

D-Day – June 6, 1944 – the Allied Forces’ invasion of Normandy, was a turning point in World War II. “I shook with fear,” says Stern, describing his first moments after landing in Normandy. “I saw human bodies everywhere, and the remains of horses and cows. Death was on the wind. The smell was unbearable. But as soon as I saw the first German soldier, the fear was replaced by a rage for revenge.”

Soon after they landed on the shores of Normandy, the Richie Boys – in teams of two or three soldiers – left their units to perform covert missions across enemy. The missions were varied: Planting disinformation by means of loudspeakers on trucks, misleading radio broadcasts, distributing fliers and more. Because they spoke the native tongue, the American army also used them to perform prosaic tasks: asking locals where they could sleep and acquire raw materials, etc.

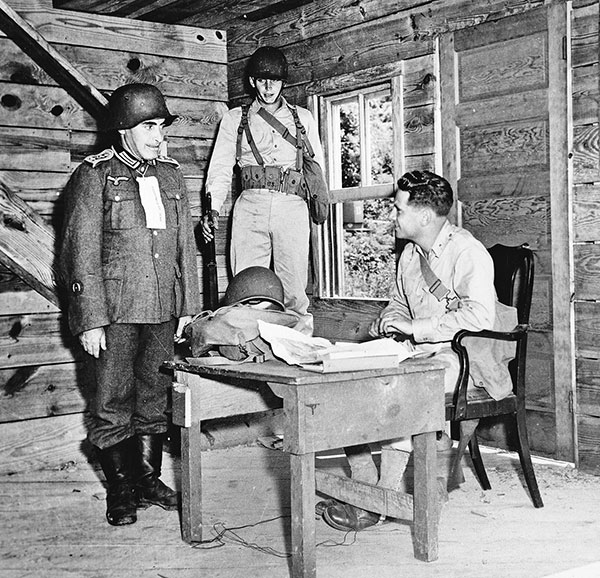

But the Richie Boys’ most crucial job was interrogating German prisoners of war. “The idea was to make the German soldiers and officers feel like they were in a safe environment, to give them the feeling that if they cooperated, we’d take care of them,” they said about their interrogation tactics. “One way to do that was not to take any notes during the investigation. Because that would immediately raise their suspicions.”

In addition, the investigators exploited the Germans’ existential fear of Russian soldiers. “The Germans were paranoid of the Red Army’s cruelty.” While Howard was interrogating a German officer, Stern, who spoke Russian fluently, would enter the room wearing a Soviet uniform with full regalia – bars on his shoulders, medals on his chest, and the Red Army’s iconic star embroidered on his shirt. “We just told them that if they didn’t cooperate, we’d have to turn them over to the Russians. That immediately did the job.”

The Richie Boys (including author Klaus Mann and photographer David “Chim” Seymour, whose exhibition of 20th-century photographs is on display at the Museum of Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot) arrived in Paris before it was liberated and fought in the famous Battle of the Bulge. In the film, they describe how they were constantly plagued by a dual fear. “On one hand, we were afraid that the Americans would mistake us for spies and shoot us, and on the other, that the Germans would discover our background.” At the end of the war, they were among the forces that liberated the concentration camps, and some of them later served as translators in the Nuremberg Trials.

The Richie Boys’ contribution to the Allied Forces was worth more than gold. General Oscar Koch, leader of the legendary US Third Army, said after the war that the boys’ success in demoralizing the German army and in obtaining intelligence about the German enemy significantly helped in breaking German resistance. True, they were not required to bring their officer 100 scalps or to crush German officers’ skulls with baseball bats, but the Richie Boys were bastards who brought us plenty of glory.