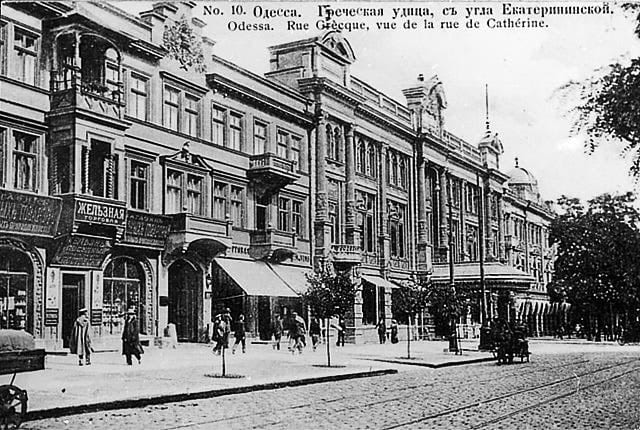

It happened in November 1919, almost one whole century ago. World War I was over, the Versailles treaty was signed in Europe, and the Russian civil war was raging, between the reds and the whites – supporters of the old Czarist regime. Jewish refugees from all across Europe, including those deported from Palestine by the Turks, gathered in Odessa, on the shores of the Black Sea. The leadership of the Odessa Committee, formerly Chibat Zion, applied for refugee status papers on behalf of the Eretz Israeli refugees, in which the applicants were required to prove their knowledge about their homeland.

Soon enough training courses were held for the refugees, both Israelis and many others, guided by the Odessa Committee people, in which they studied various details about the homeland, such as names of streets in Tel Aviv, settlements, personalities and the like. Within just a few days the number of participants skyrocketed. The Odessa Committee was running a negotiation with owners of the ship Russlan, that took advantage of the high demand and raised the price. Records describe how Jews literally sold their last belongings in order to raise money to board that ship.

Following quite a few delays, the Russlan weighed anchor, carrying 671 excited and weary people. They sailed on stormy water, suffered hard conditions, crowdedness and insufficient food. After 21 rough days, the ship finally reached the shores of Eretz Israel, but faced a strong storm, and had to sail to Egypt. Only after a few more days the Russlan returned and docked in Jaffa. Meanwhile, in the Yishuv the news – and rumors – of its arrival were spreading recklessly.

Rumors mentioned thousands of immigrants on board. Menachem Ussishkin, chair head of the Zionist Commission, assigned a huge amount of 1,000 Egyptian pounds for festive receptions in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. The Doar HaYom newspaper reported that “the entire street leading to shore was crowded with people, and many more were reaching, pouring and filling the shore, so that the shore’s policemen had to be assigned to maintain the order.”

It was believed for decades that the Russlan was the first harbinger of the third Aliyah, which is fixed in the national memory as the most ideological-pioneering Aliyah. The Russlan myth built up gradually, becoming an integral part of the Zionist mythology. But was Russlan indeed the first ship of the third Aliyah? Were the passengers on board really pioneers? Well, they were most certainly not.

Historian Prof. Gur Alroi has shown (in an essay published in the periodical Cathedra), that not only was the Russlan not the first ship to bring Jews to Israel in 1919, it was rather one of the last ones that year, and certainly did not mark the beginning of the third Aliyah, nor did it carry a larger number of pioneers than previous ships.

Why then did the Russlan win all those fame and respect? The reason laid in one small group of passengers, most unique and versatile, with a sharp historical sense. These people were about to become the cultural and political elite of the State of Israel, which was to be established three decades later. That gallery of talents and capacities was so rare, that the ship was sometimes referred to as Noah’s ark.

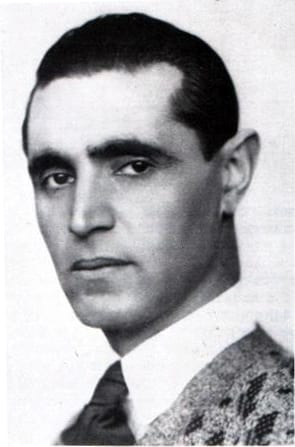

One famous passenger, who was already a celebrity then, was the literature scholar Prof. Joseph Klausner; he was joined by Israel Gury (father of the poet Haim Gury), who later became a member of the Knesset; founder of the Canaanite movement, Yonatan Ratosh; and a young anonymous woman called Rachel Bluwstein, whom everybody will call Rachel the Poetess one day.

The construction field was represented on the ship by architects Yehuda Magidovitch, who became one of the most prolific Israeli architects, master of the eclectic style in Tel Aviv; and Zeev Rechter, Israel’s greatest architects, and herald of the Bauhaus style (whose grandchildren are the musician Yoni Rechter and the actress Dafna Rechter). If you suffered from health problems onboard you could consult with Dr. Chaim Yassky, later director of the Haddasa hospital, who was murdered in the Hadassah convoy massacre in 1948; or with Dr. Arie Dostrovsky, later dean of the Faculty for Medicine in the Hebrew University Jerusalem; or even get a second opinion from Dr. Baruch Nissenboim, co-founder of Magen David Adom organization.

And the list goes on: the first caricaturist in Eretz Israel, painter and illustrator Arie Navon; his brother, the author, playwright and composer Shmuel Navon; as well as the painters Isaac Frenkel, Pinchas Litwinowski and Yosef Constant. Press and government ties were also formed on board, for example between the first woman Knesset Member, Rachel Cohen-Kagan (whose signature is on the Israeli Declaration of Independence), and the future “Haaretz” editor, Moshe Yosef Glickson. Rosa Cohen, of the Histadrut and Hagana leadership, whose son is Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s Chief of Staff and Prime Minister – was there on board of the Russlan, too. Also attended the historical cruise: dancer Baruch Agadati, founder of the Eretz Israel’s cinema: and actor Meir Teomi, (father to be of Oded Teomi), who was killed 18 years later in the terror attack in Hawaii Garden restaurant in Tel Aviv.

All in all, out of 671 passengers, 60 men and women went on the journey, and became key persons in the Jewish Yishuv and later on, in the new State. But the truth has to be faced – most of the Russlan passengers were not pioneers, but immigrants, and many of them actually left Israel long before the foundation of the State of Israel. The factual details, however, fade next to the historical narrative. Israel was a young state desperately in need of national myths, therefore the Russlan’s story was bigger than the actual facts. Back then no one knew what “fake news” was, and the Russlan story was told again and again, mainly by members of that elitist small circle themselves, who possessed finely tuned national-historical senses.

They left us various documents: memoirs, letters, journals, and newspapers. They used to celebrate the Russlan’s anniversary day, even after many years, in a festive party held annually in the “Maxim” cinema in Tel Aviv. Marking the 30th anniversary, Tel Aviv municipality finally named a street after the ship.

So here’s the concise recipe for the making of a national myth: in times of trouble, take a dangerous journey, face some natural forces, stir inside some national heroes, and make sure you assign a few collective memory agents to keep the story alive for the next generations.

Happy Sukkot!