Praying at the graves of sages is an old Jewish custom, recorded in Talmudic and Midrashic literature. Various medieval Jewish scholars discussed this religious practice, whether they approved or rejected it. A significant change regarding the prostration on graves occurred some 500 years ago, and since then it became a popular custom practiced by the social elites. Jews started to visit graves of Tanaim, usually on Shabath eve. The renown Kabbalists of Safed, especially rabbi Moses Cordovero (Ramak) and rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz (author of the famous piyut LECHA DODI) used to do it for mystical purposes.

Descendants of families expelled from Spain (1492), both Ramak and Alkabetz were raised under the traumatic deportation crisis of their parents and grandparents. The expulsion from Spain carried profound spiritual and mental implications. The Jews just could not realize how the glorious culture of Spanish and Portuguese Jewry was at once scattered and almost diminished. Vast messianic expectations were derived from this crisis: people were hoping that was the lowest point and therefore the redemption was near. At that period, many deportees from Spain discovered the “Zohar” book by Shimon Bar Yochai of the Tanaim generation and started to interpret it over and over again with a growing mystic enthusiasm.

Ramak, Alkabetz, and their followers came to the Land of Israel and began formulating an ideology that focused exclusively in the Holy Land, the “Zohar”, and the “Shechina” – the feminine divine entity in Judaism. Ramak claimed that as the Shechina was in great distress due to the exile of the Children of Israel, she was choosing to hide and become absent from our world. The Ramak and Alkabetz set their goal: to return the Shechina from her exile for the benefit of the Jews. The perfect venue for their purpose was naturally the Land of Israel, in particular Safed and the Galilee, where the authors of the Zohar lived, worked and were buried.

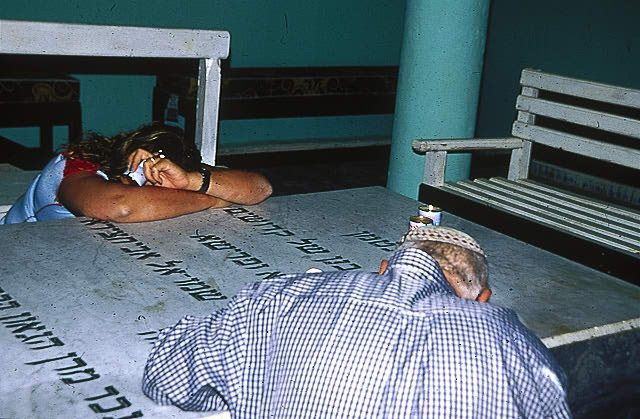

In order to understand why the Kabbalists used to perform rituals at the graves of sages we have to bear in mind that the task they undertook was not only to bring back the Shechina but also to reveal some of the holy Torah’s secrets. The Ramak developed a ritual called גירושין. Each Shabbat eve he left his home with Alkabetz the followers and took a walk in nature. They referred to it as a kind of self-exile from the home, symbolizing the Shechina’s exile from our world. In order to return her, they went to the graves of Bar Yochai and other Tanaim, and used to lie on the tomb and embrace it. Then they’d start to talk without control, in a sort of religious ecstasy. With their divine wisdom that no regular people could reach, this somewhat erotic act was their way to unite with the lost Shechina.

There were, of course, other ways to summon the Shechina back. Rabbi Joseph Karo, author of Shulchan Aruch, who lived in Safed and knew Alkabetz well, used to study all night until angels and the Shechina revealed themselves to him. However for Ramak the גירושין and the rituals at the tombs were the main mean to reveal secrets, bring back the Shechina and unite with her. As the Shechina is a feminine divine being, it is said in the Zohar that man can unite with her in the sexual aspect as well. Whether merely a metaphor, the erotic element in the image of the Shechina was undoubtedly present in the world of the Kabbalists of Safed as they were lying on the tombs while revealing sublime secrets.

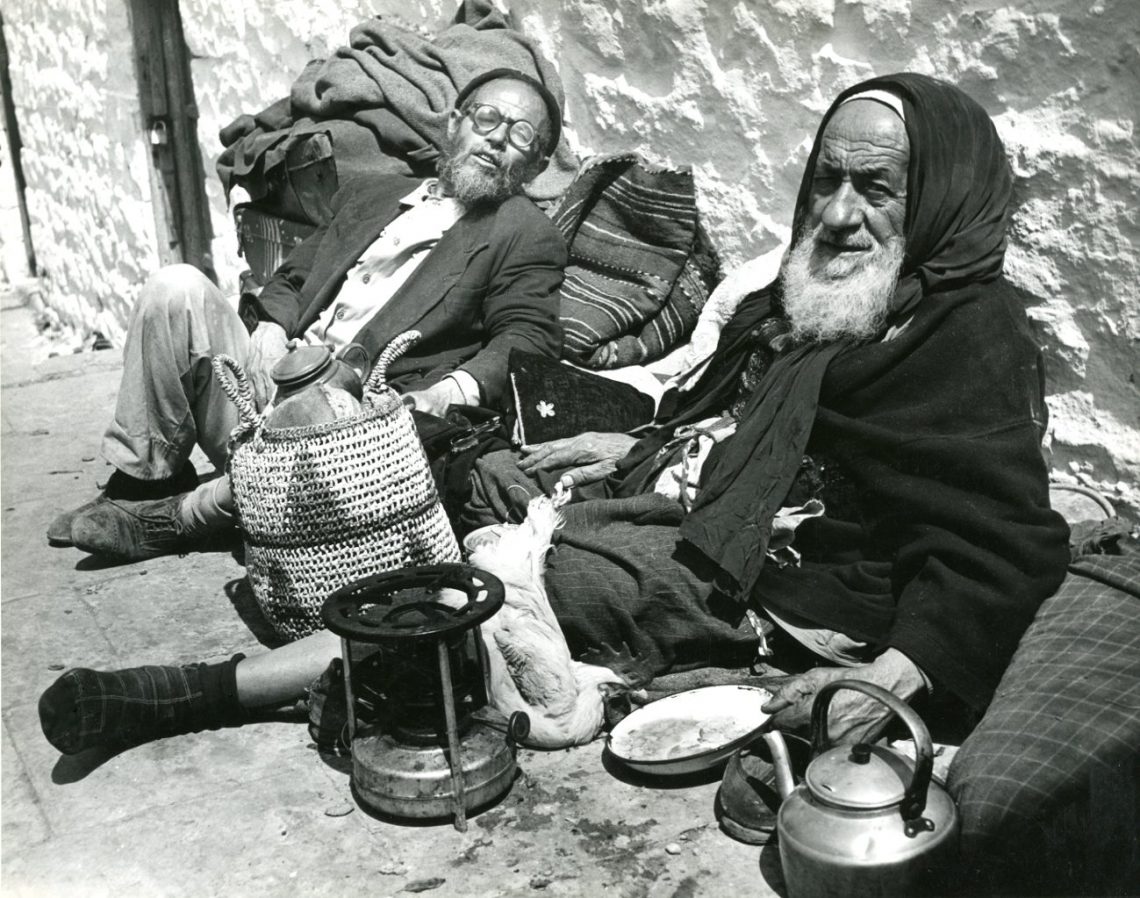

Why did they choose attending the graves? Well, it was part of the local culture in the Land of Israel, in which graves were sacred. Jews in Israel, who were isolated from the Ashkenazi and Sephardi traditions, used to pray, usually for rain, in certain places across the land which they had marked as sacred. One popular site was the tomb of Honi, where Jews and Muslims used to pray for rain.

Upon their arrival to Israel, the Sephardi Kabbalists were introduced to these local customs, and immediately added some extraordinary meanings to them. No longer did they visit the graves just for simple request for rain or crops, but for the purpose of summoning the redemption, opening a new era for humanity, bringing back the Shechina and uniting with her. They wished to get divine inspiration and to reveal divine secrets. In the 1570’s rabbi Isaac Lurie arrived to the Land of Israel and adopted the practice, as he perceived himself as following the tracks of the Tanaim and being their living reincarnation. The spiritual Jewish elite embracing the local practice changed history, and within a few centuries the custom spread to many Jewish communities. Then in the 20th century, after the establishment of the State of Israel, the tradition of pilgrimages to graves of sages was re-established enthusiastically.

Further reading:

ברכה זק. בשערי הקבלה של רבי משה קורדובירו, (באר שבע: הוצאת אוניברסיטת בן גוריון שבנגב, 1995)

רפאל יהודה צבי ורבלובסקי, ר’ יוסף קארו: בעל הלכה ומקובל, (ירושלים: הוצאת מאנגס, תשנ”ו)