The renowned author Shalom Aleichem thought Schund was trash literature and called for casting it entirely out; the critic Simeon Dubnow claimed that Schund characters are all flat and cheesy; and I.L. Peretz, the founding father of Yiddish literature loathed it altogether. But the more the refined intellectuals scorned upon Schund, the more young authors such as Isaac Bashevis Singer, Meir Shaykevich and Alexander Harkavy kept writing those dime novels. They did not have much choice, either. In those days an author who wished to make a living from writing had to dive into the popular genres or he’d starve. Meet the Yiddish ancestor of flight books and soaps: the Schund authors.

Center, Sonnenfeld collectionTowards the end of the 19th century, Schund had tremendously high rating. It addressed the masses; Desperate Jewish Housewives adored it, newspaper sellers in Warsaw depended on it for their living, it was popular in Vilna and inspired plays adaptations staged in Yiddish theaters in New York.

The literal meaning of Schund in German is the stench felt while skinning a slaughtered animal. The actual meaning is badly written, cheap, unsophisticated literature.

Schund was very popular among non-Jews in Europe during the 19th century. In the 1870’s it was adapted to Yiddish and was addressing the simple Jews, who were not used to quality literature. The financial success of Schund attracted many authors to enter this new genre. They published detective fiction, thrillers, westerns, science fiction and adventures, and of course the most admired category – love and romance.

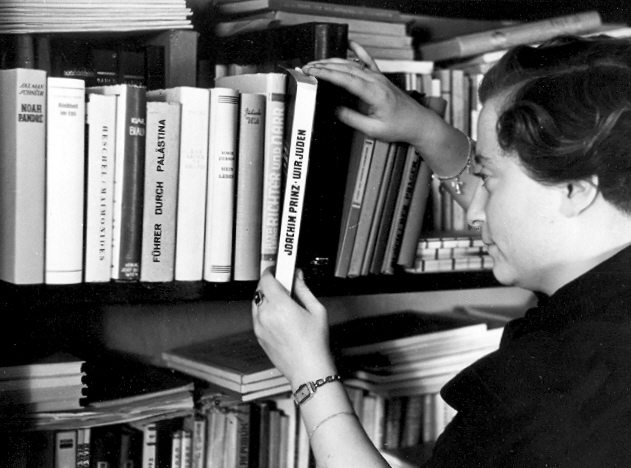

In order to save costs, the books were produced of cheap paper and distributed in newspapers stands and public libraries. The respectable bookstores in Warsaw, Vilna, and New York dared not sell what they considered abomination.

As for the content, most of the Schund stories had a twisted thrilling plot with sentimental love affairs which sometimes took place in far exotic places, while in other times in close familiar environment. The characters were flat, the protagonists were counts and princesses, or in some cases simple, easy to sympathize figures. Good and evil were well defined, no gray areas, no depth, and all the stories had a happy ending.

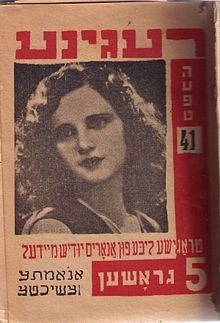

The publishers used to sign authors on contracts that allowed them to bluntly interfere in contents, titles and even in the author’s name or pseudonym. The only purpose was to sell as many copies as possible. Titles were the most crucial issue, typical titles including “Princess in the Woods”, “The Educated Killer”, “Love for Sale”, and some titles defying today’s p.c. decorum, such as די ביטערע נקבה “The Bitter Female” by Getzel Selikovitsch, who kindly dedicated it to his sister.

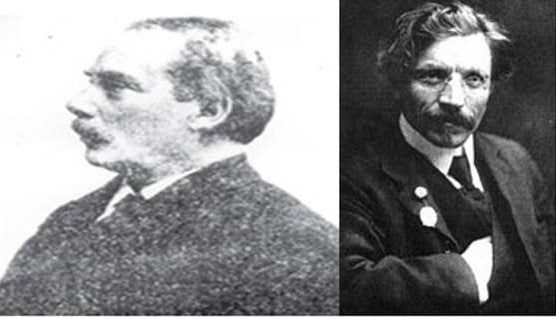

The most illustrious Schund star was Nahum Meïr Schaikewitz (known by the acronym Shomer). Born in Russia, he started his literary career in 1876. Shomer lived and worked mainly in Vilna and Odessa and was a prolific author who published 15 novels in Hebrew, 205 novels in Yiddish, 50 plays and lots of other works of literature. He headed the best seller lists for years, envied bitterly for this by respected authors such as Sholem Yaakov Abramovich (Mendele Mocher Sforim) and Shalom Aleichem. In 1888, the latter wrote a fierce essay on Shomer, called “The Shomer Trial”, in which he wasn’t only criticizing Shomer’s literal work but also attacking him personally. Some say that Shomer was so offended by Shalom Aleichem that he decided to leave to America – at the same year. Before leaving, he composed a response and published an essay called “Let there be Light”, in which he praised Schund as meeting the spiritual needs of the simple Jews. Reaching New York, Shomer’s career was not held back, he vigorously kept on publishing and editing Yiddish magazines.

Judging only by sale rates, Schund significantly prevailed over the Yiddish fine literature – that is, until both styles were ultimately buried because of the Holocaust.

In the beginning of the 20th century the Schund sphere saw yet another new creature – the serial novels – tens of thousands of sequential Schund novels printed and distributed in newspapers. Encouraged by the commercial success, editors of large Yiddish newspapers in New York such as Forverts פֿאָרװערטס, who hosted Nobel awarded authors such as Bashevis Singer, published not one, but at some point even three sequential novels at the same time.

Back in the old country Yaakov Yatskan, the legendary founder of the most popular Jewish newspaper in Poland, Haynt, took this format a step further and made the sequenced thriller an innate component of the newspaper. Soon enough Schund became integral part of all dailies. Statistics from 1932 show that out of 50 daily Yiddish newspapers distributed worldwide, 30 published over 300 Schund sequenced novels. Most of them formatted, as critic Nahman Meisl described it, according to a fixed formula, by anonymous writers or by authors too embarrassed to sign their real name on them.

The success dropped off gradually until Schund was completely gone, after most of the Yiddish readers in Eastern Europe perished in the Holocaust. Both Schund and fine Yiddish literature died along with the Jewish readers.