Radical works of art may raise arguments and debates about whether they belong in the public arena and might even destroy the career of an appreciated author, who only wished to push some boundaries. That was the case of the Yiddish author Shalom Asch.

Ash was born in 1880 in Kutno near Lodz, Poland, to a traditional family. From a young age he has familiarized himself to western literature, he was an autodidact and knew Hebrew, Yiddish and Russian from home, and also German, which he learned by himself. In his youth he tried to write in Hebrew, then soon switched to Yiddish. At 23 he published his first stories collection.

Through his biography resembles many others of writers of his generation, at an early stage of his work he proved to be an outsider. He did not wish to become yet another author who describes life in the Shtetel. Living in intense political times, when many Jews were drawn to Socialism and Communism – and Zionist as well, he was deeply affected by the hardships of the lower classes. Asch begun to write stories and plays on the margins of the Jewish society. He wrote about Jewish prostitutes, thieves and criminals.

The Jews in Asch’s stories are preoccupied with materialism and sexuality on the one hand, and with redemption and pardon appeals on the other hand, accompanied by a profound sense of sin and guilt. Asch first provoked rage and controversy when he published a play called “The God of Vengeance”, now also playing in the Israeli Cameri Theater. The play was about a seemingly religious family, the father an observant Chasid who tries to maintain a descent appearance of a good family, while secretly running a brothel in his basement, unaware that his daughter fell in love with one of the women he pimped. Though highly successful in Europe, the American Jewry resented the play, fearing it might arouse Anti-Antisemitism, and protested against it. Shalom Asch benefited from the protest – he was famous as a young trailblazer, gradually turning into one of the famous Yiddish authors in the world. His books were translated to various languages and reached even non-Jews, who acknowledged his literal talent and originality. Some referred to him as “the Yiddish Dickens” (or the Jewish Dickens), especially for his focus on the lower classes.

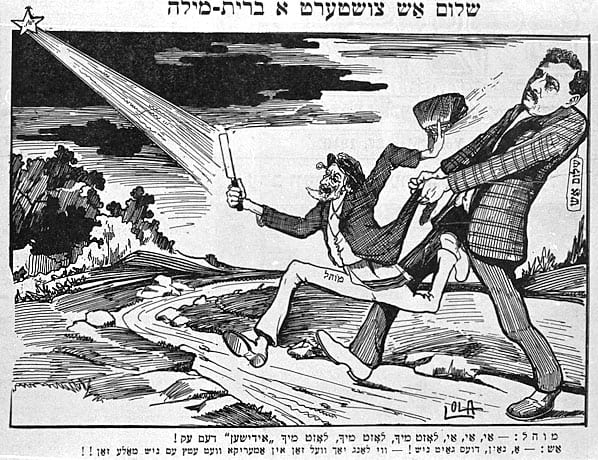

At the same time, Asch had a bitter dispute with the orthodox society, due to an affair that took place in 1907, when a Jewish baby died in Warsaw before his circumcision, and the burial society (Chevra Kadisha) insisted on circumcising him before burial, in spite of the parents’ objection. Asch wrote harshly against the Chevra Kadisha, condemned the Brith ceremony they insisted on and called it a barbaric act, and published it in a Polish, slightly Anti-Semitic magazine. His popularity was not damaged, though. He was still the leading Yiddish writer, choosing each time a surprising topic: Jewish Anusim in Spain, or the false messiah Shabtai Zvi, to mention just two. He visited the land of Israel several times, lived mainly in Europe, and at the eve of the second World War he immigrated to the United States.

Then his popularity dropped almost overnight. It was due to an exceptional essay published in 1939 called The Man from Nazareth, dealing with the life of Jesus from a sympathetic point of view. Up until then, there were authors and scholars who thought of Jesus as a Jewish moral prophet who had nothing to do with Christianity. But Asch’s timing was unfortunate, while the war was destroying Europe and the Nazi’s atrocities towards the Jews in ghettos and camps were already known. In that point of time, the fact that Asch wrote about the founder of Christianity positively, made him a target to direct personal attacks.

His reaction to the attacks against him made it even worse. Not only did he not apologize, he started to talk about Jesus as a true messenger from God, and implied he could be a true messiah. And not only that, he wrote a sequel book called The Apostle, dedicated to the life of Paul, the apostle who shaped Christianity as a new religion. Whereas Jesus was somewhat accepted as a moral figure, Paul was way too much – the man who claimed that God has abandoned the Jews, that circumcision and Mitzvot were no longer required – such a character could not pass as a Jewish author’s protagonist. Asch was looked upon as a Jew who converted his faith to Christianity.

Regardless, Asch still considered himself Jewish, in fact it seems that “The Apostle” reflected his identification with Paul, as a Jew who started to believe in Jesus. Possibly Asch did discover a certain religious faith in Christianity but would not under any circumstances turn his back to his Jewish background. But for his Jewish readers this was totally unacceptable. Jewish journals refused to publish his stories, all but one Communist paper. When the stories did get published – in a small Communist paper – Asch was accused by the American congress of political subversion, which deteriorated his reputation even more.

In his last years, Shalom Asch made a most surprising move. Though he always was sympathetic to the idea of Jewish nationalism, he did not care so much for Zionism. But in 1955, after being an outcast for years, he decided to come to Israel, and settled in a small flat in Bat Yam. Most of his Jewish readers, who indulged on his literary pimps and criminals, refused to accept the complex identity of the perplexed author himself. Asch died two years later, while visiting his daughter in London. Britain’s chief rabbi refused to bury him in a Jewish cemetery, so he was buried in a small reform ceremony, with only a handful of mourners.