Growing up as a religious boy in Haifa during the 1990s, I used to argue with a secular boy my age, a sharp clever kid called Baruch, named so by his father, a Math Professor in the Technion, who was an enthusiastic fan of the greatest Jewish heretic ever – Baruch Spinoza.

I can still remember the passionate theological arguments between Baruch and me. Our budding intellectual Eros; the strong motivation to refute one another’s case, and how each time it ended with the neighbors shouting at us to keep it down, and the two us abandoning the loud debate and go to the court to play together.

Our neighborhood was densely populated with “Yekes”, Jews from Germany, who worshiped their sacred Siesta, from 2 till 4 o’clock, more than anything else. Since then, many taboos in Israeli society were broken, and most of the common denominators are long gone. Religious and secular neighbors arguing with one another with mutual respect, and then forgetting about it and playing together – seems almost impossible nowadays.

I grew up and left Haifa, but wherever I went, I did not stop looking for Baruch. Then, one day I finally found him, I finally encountered what my soul was wanting – in the late Yirmiyahu Yovel’s book “Spinoza and Other Heretics”.

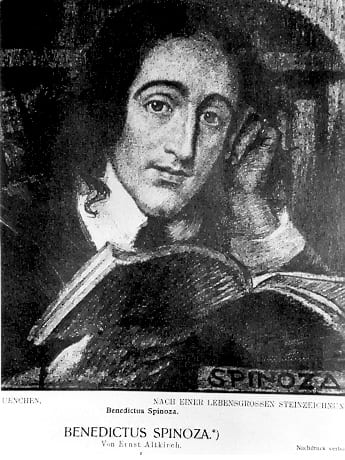

This year marks 363 years to the excommunication issued by the Jewish community of Amsterdam on the solitary genius, Baruch Spinoza, whose impact on western philosophy was so huge, that Friedrich Hegel, the great philosopher, said that “You are either a Spinozist or not a philosopher at all”.

Sometimes I like to picture Spinoza in his small poor bedchamber, which he rented outside of Amsterdam after the community banned him. I wonder how he must have felt, that humble and diligent lens grinder, when he had to listen to his fellow Jews curse him “like Joshua banned Jericho, with the curse with which Elisha cursed the boys and with all the curses which are written in the Book of the Law”. What went through his mind when the community leaders warned the members “We order that no one should communicate with him orally or in writing, or show him any favor, or stay with him under the same roof, or within four ells of him, or read anything composed or written by him.” (from the excommunication document)?

Historical records portray Spinoza as a solid man whom no one could cause to lose his temper. Stubborn, totally devoted to the geometrical pattern of syllogism based on pure intellect, that only a great mind like his own could form.

He was only 24 year of age, not much older than me and my youth opponent, while ruthlessly attacked from all directions. On one hand, the Calvinist Dutch church condemned him for challenging the most principal faiths. And on the other hand, the Jews of Amsterdam, descendants of the Anusim of Portugal, in an ironic act historical blindness, acted against him in the same strategies the Inquisition has acted against their ancestors in Spain and Portugal: denunciation, banishment, and cruel isolation.

What amount of inner strength he must have had, to hold on and not give up. He even turned down a job opportunity offered to him by his colleagues in the Heidelberg University, explaining that it might interrupt his independent thinking. Only a man with this kind of powerful personality and rare confidence could have established the most important movement of the modern era – the secularization.

Yes, Spinoza is responsible for the beginning of the secularization process!

True, no one visits on his grave or holds festive pilgrim celebrations or mass memorial services for him, but billions of secular, atheist people living worldwide today, owe their freedom to that gifted Jewish Amsterdam scholar. And what’s most funny, is that Spinoza was nothing of an atheist at all, on the contrary, he was “intoxicated by the divine idea”, to use the words of the German poet Novalis. Spinoza believed that the God of wisdom was everywhere – in the laws of nature, in political philosophy and in man’s good virtues.

The first scholars to discover – or rediscover – Spinoza’s works were the giants of enlightened philosophy, Kant, Hegel, and later on Nietzsche. Moses Mendelssohn, the father of the Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment) movement, had a high opinion of him, though he strongly disagreed with his ideas about the meaning of Torah and mitzvoth. Jewish scholars gradually began to be more familiar with Spinoza’s bold ideas. The first Jews that reached out for Spinoza were maskilim such as Abraham Krochmal and Fireberg. Herzl and the Zionist movement joined them later on and gladly adopted Spinoza’s philosophy. He granted the Zionist movement with the perfect model of a secular Jewish state. “A day will come, when the time is right, as matters of people are constantly changing, they shall once again establish their kingdom, and God shall once again choose them”. When Spinoza wrote these words in 1670, 227 before the first Zionist congress, in his Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, he must have pictured the pioneers who left their faith, in his imagination.

One specific moment marked the reconciliation between Spinoza and his fellow Jews. It happened during a lecture marking the 250th anniversary to his death. In 1924 the historian and Professor of Hebrew Literature, Joseph Klausner from the Hebrew University, announced that the excommunication was lifted. “250 years after his passing away, we now call to Spinoza from our synagogue here on top of Mount Scopus, which is the Hebrew University of Jerusalem – the excommunication is lifted! The Jewish nation’s sins against you are now repented! You are our brother!”

This public absolution was followed by a renaissance in the relations between Spinoza and the Jews. A flood of studies, essays and tractates was poured heavily. In 1953 prime minister David Ben Gurion published “Amending the Injustice”, where he urged to publish all Spinoza’s writings in Hebrew translation right away. “The corpus of Hebrew literature is not complete without the works of Baruch Spinoza, that are an integral part of the spiritual assets of the Jewish people”, Ben Gurion said. The academy took up the challenge as well as various memorialization organizations in the young state. Streets, institutes, and foundations were named after him. This tendency peaked in 1988, when Yirmiyahu Yovel, laureate of the Israel Prize, published his book “Spinoza and Other Heretics”, the most in-depth, comprehensive works about the first secular man in the history of mankind.

The story of Spinoza – the ban, the hatred, the incitement, then the gradual reconciliation, can be a fascinating test case to the fateful secular-religious tension that’s been tearing us apart for centuries. Can we do that? Can we really go on arguing with one another and still maintain mutual respect, and then play together in the hood court? Only Spinoza’s God knows.

Gmar Chatima Tova everybody.