“In our home, we didn’t talk about anything related to the Holocaust or the pogroms,” recounts Ilana Bar-Gil from Modi’in. “I was in shock when my mother began receiving reparations from Germany. And then, little by little, she started telling us what had happened. In 1945, my mother, Dina, was nine years old, the middle child of six siblings. She doesn’t remember a lot about the pogroms, but does remember being hungry all the time. They would rummage through garbage cans for food. One day, she found a piece of bread covered with rat droppings. But because she was so hungry, she brushed away the droppings with her fingers and ate the bread.”

After being under Italian- German occupation, Libya was conquered by the British in January 1943. The British authorities repealed the race laws that had been enacted and put an end to the oppression and humiliation that the Jews had been subjected to. And, of course, they lifted the threat of the Final Solution. Jews who had been forced into labor or were incarcerated in concentration camps returned to their homes. About four months later, Tunisia was also liberated, and the Jews who had been deported there and taken to detention and labor camps came home as well. When the war ended, the Jews who had been sent to and survived the concentration camps in Europe also returned to Libya.

Some of the soldiers who liberated Libya were Jews from Mandatory Palestine who had volunteered for the British army. Their ties with the local Jewish population led to the revival of the Hebrew language movement and Zionist activities. The local communities and the Jewish education system resumed their regular work. Even emissaries from Mandatory Palestine came to Libya despite the restrictions imposed by the British, who prohibited Hebrew teachers from entering the country. Furthermore, the British did not agree to reinstate the activities of the Tripolitan Zionist Organization.

On the one hand, the country had started getting back to normal following the war: the economy was growing, industrial production, commerce and construction were bouncing back, and the relations between Arabs and Jews were very tight. All Libyans felt they shared a common post-war destiny and nurtured the hope for a better life. Libya’s economic prosperity was, however, short-lived. The British were still engaged in fighting Nazi Germany in Europe and neglected the countries they had liberated in North Africa.

As the recession deepened and unemployment increased, the economic crisis gave rise to a resurgence of Arab nationalism. Al-Hizb Al-Watani, one of the leading nationalist movements, exploited the uncertainty of Libya’s political status and pushed for full and immediate independence. Hatred of foreigners and minorities swept the streets and, unsurprisingly, the Jews were the first to be targeted.

It didn’t take long for things to come to a head. As often occurs, it started with a blood libel. Unfounded rumors regarding brutal attacks by Jews against Arabs in Palestine began to spread, fueled by claims of the alleged desecration of Muslim holy places in Jerusalem.

On November 4, 1945, a daily newspaper published a long article that described and supported the mass demonstrations against Jews in Syria and Lebanon. The pogroms in Tripoli broke out that very same evening. Thousands of frenzied Arabs, armed with clubs and iron bars, burst into Jewish neighborhoods. Crushing everything in sight, they murdered, burned and tortured Jews, while the British stood by and did not intervene. Soldiers serving in the Jewish Brigade of the British army tried to extend assistance on the first night of the pogroms, but their commanding officers barred them from leaving their base and getting involved. Some disobeyed those orders, broke into the armory on the base, and went out to defend their brethren. A number of them were arrested and sent away. Others continued to help remotely by keeping the world and the Jewish community in Palestine abreast of what was going on so they could intervene in the matter.

During this period, only one Jewish company of the British army was stationed in Tripoli. The soldiers continued to assist the local population, coached the youth, and also tried to set up a local branch of the Haganah (the main Jewish paramilitary organization in pre-State Israel). As the situation got worse, their aim was to train the Jews to defend themselves against the rioters. The work done by the Jewish soldiers was brought to the attention of the British authorities, who blocked the initiative and promised to ensure the safety of the Jews.

“My grandfather’s brother, Ezra Naim, lived outside the Jewish quarter,” recalls Haim Naim, who was eight years old at the time. He provided the following testimony to the “Seeing the Voices” project, a joint undertaking of the Ministry for Social Equality, Yad Ben-Zvi, and ANU-Museum of the Jewish People: “Because Ezra didn’t have the financial means, he lived 1.5 kilometers from there in an Arab section of town. He was very religious and very naïve. He actually managed to escape before the riots started and almost made it to the Jewish quarter. But then he remembered that due to the hasty departure, he had forgotten to take his phylacteries and prayer shawl with him. So, he decided to go back to his house. The rioters caught him there and murdered him. They butchered him. After the pogroms ended, my father went to see what had happened to him and found him slaughtered, drowning in his own blood.”

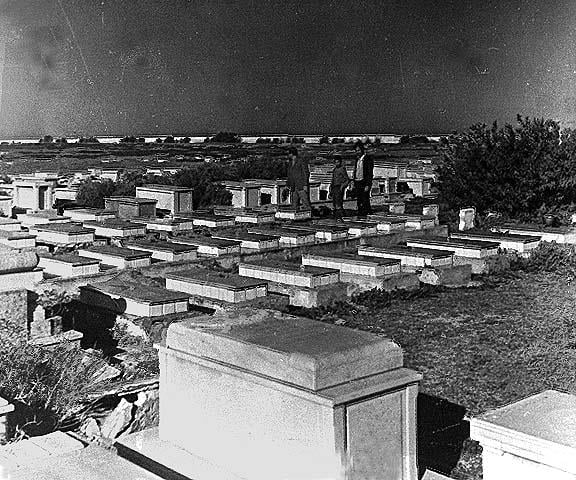

The pogroms lasted four days and four nights. Entire families were brutally murdered, and some were burned alive. The 133 victims left behind 30 widows and 92 orphans. Many others were injured, and some died of their wounds later on. Several remained disabled for the rest of their lives. There were reports about women and girls who had been raped and whose lives were spared only because they agreed to convert to Islam. Business establishments were looted and destroyed and synagogues were desecrated. 12,000 Jews were left without a roof over their heads and with no source of income.

The survivors were housed in extremely crowded refugee camps, where the conditions were very harsh. Ultimately, the British arrested around 600 Arab rioters, but fewer than half of them were brought to trial. Some were acquitted. Ten Jews were also arrested for having the courage to defend themselves rather than be murdered, and they received prison sentences.

Three weeks elapsed before the British authorities managed to convene a meeting on November 27th between representatives of the Jewish and Arab communities, whose purpose was to restore peace to the streets. After lengthy discussions, the parties agreed to a truce. It lasted until the outbreak of the next incident, which came in the form of the Tripoli pogroms in 1948.