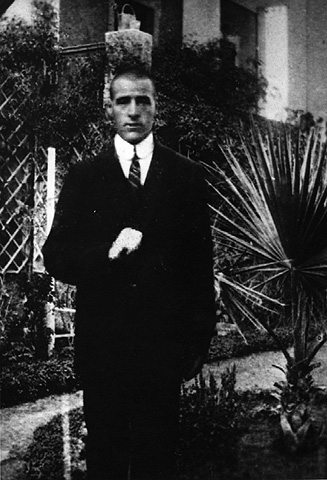

“It is good to die for our country” is undoubtedly one of the most famous quotes in Israeli collective ethos, referred to Joseph Trumpeldor before dying from his wounds in the battle of Tel Hai in 1920. At that point Trumpeldor was already a famous hero, mainly for his glorious actions in the Jewish Legion during World War I. However less is known about his leadership qualities demonstrated years earlier, during the Russo-Japanese War, in which he lost his hand and was captured by the Japanese.

A certain background about early 20th century Japan is in place in order to realize how Trumpeldor earned his reputation in the Japanese captivity of all places. Japan was a rising empire aspiring to occupy as many territories as possible, especially from the declining neighbor, China. Soon Japan and Russia were struggling over territories in East Asia. In 1904 the Japanese decided to forsake all diplomatic efforts and declared a war against Russia. Jews all over the world wished to see Russia defeated.

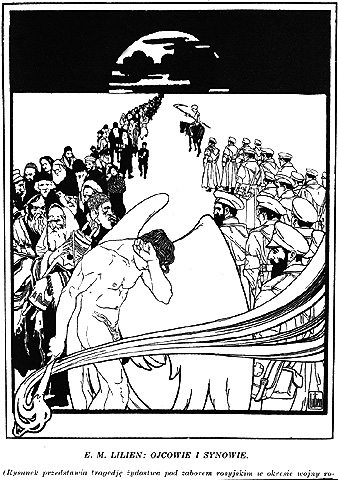

Russia had a bad international reputation as being an anti-Semitic place. The Kishinev pogroms of 1903 were widely covered in world press and the news and images were appalling, which was why Jews outside of Russia publicly supported Japan. According to Meron Medzini’s research, Jacob Schiff, a German-Jewish banker living in the United States, loaned the Japanese over 50 million Sterling as a contribution to the war efforts. Having contacts within the American government he also encouraged the president to help the sides reach a truce, from the Japanese would benefit. When Japan indeed won the war, many Jews around the world rejoiced at the Russians’ defeat. Naftali Herz Imber (author of “Hatikva”) even composed a victory song praising the Japanese emperor and the Japanese nation.

Thus, when the war ended, the Japanese were convinced that Jews are an extremely strong nation, financially wealthy with international diplomatic contacts network, and honored them greatly for that. They treated Jewish prisoners of war, including Trumpeldor, relatively good. They had other reasons though; they wished to become accepted in the west and let the world see how humane they were with their war prisoners, both Jews and non-Jews alike.

Trumpeldor quickly took advantage of the opportunity to make himself noticed. Though not too keen to serve in the Czar’s army, well aware of the Antisemitism within the army as within the entire nation, he did serve in order to refute the anti-Semitic ideas; he also wished to integrate into Russian society and culture. His captivity, however, changed it all.

In August 1904 Trumpeldor was severely injured in a battle and had his arm amputated. After recovering he went back to his unit. His base was captured by the Japanese in early 1905. The Japanese physicians re-operated on his amputation injury and managed to prevent a life risking infection. Not only did they give him an improved medical care, they also wished to demonstrate a moderate treatment towards the Russian prisoners of war, and as mentioned above, they perceived the Jews as a special elite. Therefore they allowed the Jews to have an autonomous community life within the camp. The Jews resided separately and had their events and culture activities, and even some Zionist activities.

Trumpeldor was drawn to Zionism even before the Russo Japanese war, but in captivity, his Zionist and political tendencies strengthened. Now was his change to become a leader. Up until then he mostly associated with assimilated Jews, and was encouraged by his family to be devoted to studies in Russia and serve in the army. But now, in captivity, surrounded by Jewish and Zionist friends, he became an enthusiast. His energies, until then focused on being a student and soldier, were now put into establishing and maintaining a Jewish community in the Japanese captivity.

He arranged for various activities: Trumpeldor had the prisoners publish a newspaper in Yiddish called “דער יודישער לעבן” – The Jewish Life, which was distributed inside and outside the camp and was quite successful; he organized a school for Jewish soldiers, which soon became well known throughout the entire camp, attracting non-Jewish soldiers who wished to improve their education.

Though he was not religious himself, and did not care much for holidays and prayers, Trumpeldor made sure that all the prisoners’ religious needs are met. This included prayers, holidays, kosher food for Passover, New Year cards, four species for Sukkot and the like. His inmates were assimilated Jews, Zionists, traditional and even religious and orthodox. They admired his altruism and respected him deeply.

When he was released, after the war ended, Trumpeldor was determined to come to Israel and carry on with his Zionist activity. While still in captivity he had correspondences with Zionist leaders. A few years after his release, leaving behind prospects for an outstanding military career – he came to Israel, to Tel Hai – and the rest is history.

Further reading: בצל השמש העולה: יפן והיהודים בתקופת השואה/ מירון מדזיני, הוצאת האוניברסיטה הפתוחה