This coming Yom Kippur, just like every year, during the Musaf prayer, the famous piyyut “Unetanneh Tokef“ will be once again sung and touch all hearts in Ashkenazi synagogues and in part of the Sephardi and Yemenite ones as well. The piyyut opens with the words “Let us now relate the power of this day’s holiness, for it is awesome and frightening. On it Your Kingship will be exalted; Your throne will be firmed with kindness and You will sit upon it in truth”. It has been one of the most renowned texts in Jewish liturgy for centuries, which received the highest honor of being read and sung on Yom Kippur. The text is a description of how all people shall be judged for good or bad, and includes depictions of the various death punishments, while praising God’s greatness. In addition to the reverence filled text, there is also a unique historical story behind the composition and its circumstances.

The exact origin of the piyyut is obscure. There are several assumptions as to the identity of the author and the precise period of publicity. Yet based on manuscripts, the piyyut’s poetic style, and the fact it was among the findings of the Cairo Genizah, it is widely agreed that it was composed in the Land of Israel in the early medieval period. Some researchers attribute the poem to an Israeli poet called Yannai, however others disagree. Since the middle ages various psuedepigraphic were spread among Ashkenazi and Italian Jewry regarding the piyyut. These traditions were eventually fixed in the 13th century in the essay “Or Zarua” by rabbi Isaac ben Yehoshua. Rabbi Isaac attributed the piyyut to different time, place and author altogether. Usually, in order to create authenticity for a work, it is transferred to an earlier time, so as to give it the prestige of an ancient respected source. But the case of “Unetanneh Tokef” was quite reversed. It was attributed by rabbi Isaac to a later period than the actual composing time.

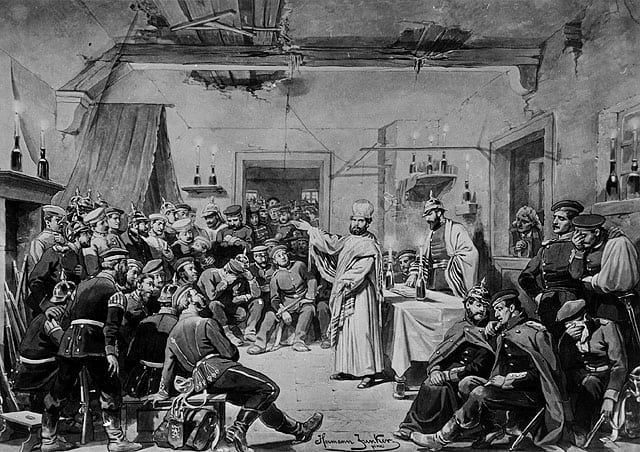

In his essay, rabbi Isaac unfolded a story delivered by rabbi Ephraim of Bonn in the 11th century, about rabbi Amnon of Mainz who was a friend of the local Christian ruler, who urged him again and again to convert to Christianity. Whether out of fear, courtesy, or sincere intentions, rabbi Amnon promised his friend he will consider it for three days. Then he felt deep remorse and suffered a lot. When the time came, he tried to avoid the bishop, who was surprised at his friend’s behavior, and soon sent people to force him in. Rabbi Amnon then begged his friend to cut off his tongue that made him utter the words he regretted so much. The furious bishop told him he would not cut his tongue, but rather his legs and arms. A horrible torture then begun, where Amnon’s limbs were amputated one by one, yet he refused to convert. Tortured and mutilated the miserable rabbi Amnon was taken to the synagogue, and just before breathing his last breath – he recited the entire piyyut “Unetanneh Tokef”. After his death, the martyr Amnon came to rabbi Kalonymus in his dream and taught him the piyyut test, ordering him to spread it among the Jews in his memory.

Various studies have shown that the basic story that appears in “Or Zarua”, about rabbi Amnon from Mainz, did appear in earlier manuscripts, and though had many adaptations and was added the elements of the Christian tortures, was indeed attributed to the 11th century rabbi. Historian Avraham Frenkel managed to draw the paths in which the piyyut arrived from the Land of Israel to Italy at an early stage, as the two communities had close ties. From Italy the text traveled north, to Ashkenaz (Germany), and various interpretations were added on top of it. At an early stage the piyyut was attributed to rabbi Amnon of Mainz, therefor it is possible that although living in Germany, he had Italian origins.

The variety of stories about the piyyut teaches us a lot about the period in which it became popular. Written as a general text about the fate of man, it became identified with the harsh fate of Ashkenazi Jews in the middle ages. The story of rabbi Amnon resembles martyrs story, both Christian and Jewish that were very common since the 12th century, for example on how Jews during the first crusade would rather take their own lives and even to kill their children and not be converted by the Christian rioters. Some researchers claimed that rabbi Amnon was not a real man but a symbolic story about the hardships of the Jews. However, it is also possible that he was a real person, who once the piyyut arrived at Italy started to take credit for it.