We can venture a guess as to what Walther Rathenau had on his mind during the few moments he lived after extreme right-wing assassins riddled his upper body with bullets in his hometown of Berlin. Perhaps one of the early 20th century’s greatest statesmen thought: My lifelong conflict has finally been solved. I am finally rid of the internal struggle that has plagued me since birth – the question of who I am. A member of an inferior Asian tribe or the exalted Prussian elite? A descendant of Moses and Aaron or Schiller and Goethe? A Jew or a German? This man’s heart grappled with many contradictions that ended in a curse rising from the basements in proto-Nazi Germany’s capital: You are a Jew. That is what the callous uncircumcised have ruled. In your home. As you go out. And on the day of your death. One can only hope that at that moment, young Walther was finally at peace as he returned to his Maker.

One of the most astounding factors in Walther Rathenau’s life was how his looming image was erased from Jewish memory. In other words, how the State of Israel failed to memorialize one of the 20th-century’s most brilliant and highly esteemed statesmen, who spared Germany from post- World War I bankruptcy and served as the Weimar Republic’s legendary Foreign Minister? It is quite amazing.

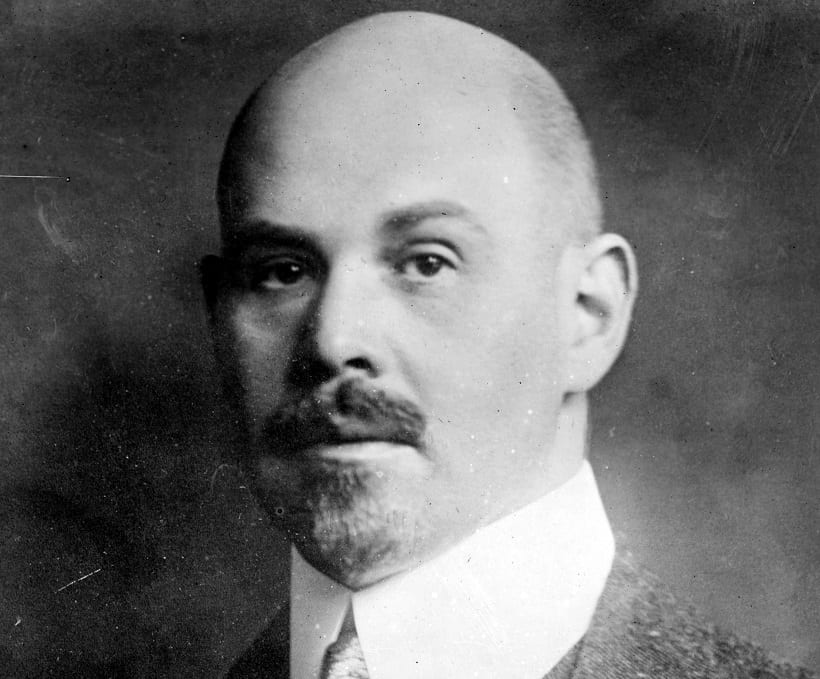

Let us make some sense of this and rectify the injustice to some extent. Rathenau was born in Berlin in 1867 to Matilda and Emil, an engineer among Germany’s greatest industrialists. Nahum Sokolow described Emil as, “a youth like a cedar with the body of a mighty oak [as in Psalms 92:12 and 29:9, respectively]. His appearance is that of one who lives on the land, a stalwart of the Jewish race.”

In 1881, Emil attended the International Exposition of Electricity in Paris and saw an electrical light bulb invented by one Thomas Edison. That turned the Jewish engineer on, and he immediately pulled out his notebook and sketched the bulb. When he returned to Germany, he upgraded Edison’s invention, and years later, established Germany’s first electric company. In time, he brought the telephone to Germany and ushered in the empire’s wireless age. Upon his death in 1915, his electric company employed about 70,000 workers.

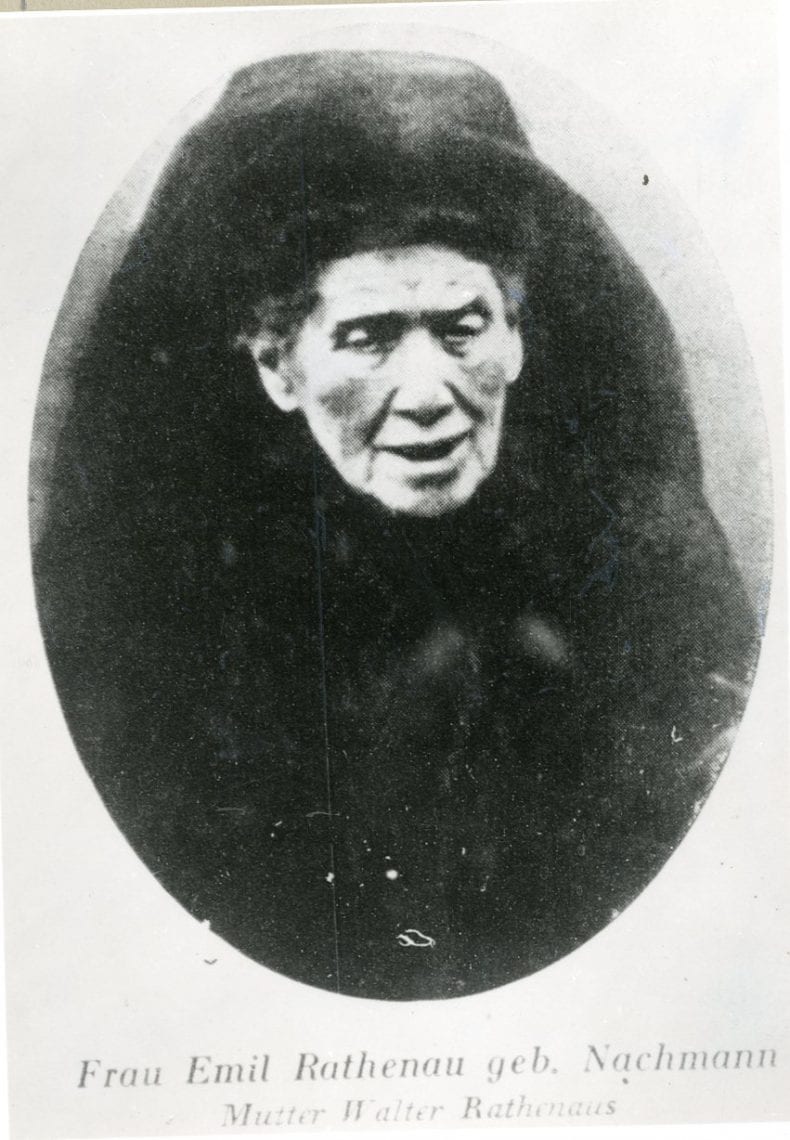

His son Walter, the hero of our story, was raised in lavish wealth on the family’s posh estate in the Berlin suburbs. He was surrounded by servants, nannies, tutors, and works of art. His cousin, Jewish artist Max Lieberman, was among the 20th century’s greatest impressionists. Walther spoke Parisian French from an early age and peppered his haute German with quotes from the finest romantic literature. His mother, Matilda, took great pains to educate her children. The value of education reached a pinnacle in the late 19th century and German-Jews placed themselves at the peak of culture. Two decades after achieving emancipation, they were not about to pass up this opportunity to be more German than the Germans.

Walther epitomized the German-Jewish ideal at its zenith. His unbridled ambition was palpable from a young age. He dabbled in drawing, sculpture, and literature, and grew to – at least – hold himself in high regard, writing, “Three great men have existed since the Creation: Moses, Jesus, and I will not mention the third.”

Great things were expected of young Rathenau, but one thing continued to disturb him – that he was a circumcised Jew. All the wealth, opulence, and talent did not prevent the local German nobility from reminding him that he was inferior to them. When he was a private, the army refused to grant him – and all the other Jews – the rank of officer in the elite Prussian battalion in which he served. At first, Walther tried to shake off his Jewish extraction. On March 6, 1897, he published an article entitled, “Shema Yisrael (Hear O Israel),” in which he called to Jews to expedite their assimilation and embrace Prussian mannerisms. At the top, he included a portrait of Jews that he saw in a cultural center in Berlin: “At the heart of German life, lies a special human race. Loud, gaudily dressed, self-absorbed, temperamental, and restless…An Asian tribe on the sandy plains of Prussia…not a living organ within the people but a foreign organism in its body.”

His father Emil was very angry at this son. He purchased every copy of the paper on which he could get his hands. Walther later expressed remorse regarding the article, claiming that he was profoundly depressed at the time. We can believe him. He insisted on remaining a Jew despite his many friends in the German-Jewish elite who converted – joining the German-Jewish multitudes who prompted Jewish poet Heinrich Heine to write, “you crawled to the cross.”

At age 30, Rathenau managed one of his father’s electrochemical plants in Bitterfeld; and 10 years later, he served on the boards of nearly 80 major companies. He also painted, sculpted, played the piano, and wrote books of poetry, politics, philosophy, and economics.

His greatest achievement came in World War I, when he was appointed to coordinate financial matters during the war, and in no small part, ensure Germany’s economic survival. Despite his accomplishments, he was forced to leave his post because of opposition among sectors of the government to his Jewish origins. His talent ultimately trumped his extraction. In 1919, Rathenau was nominated chief financial advisor to the government, and at the end of the war, he served as its minister of rehabilitation of the Weimar Republic, Germany’s last stab at founding an enlightened, democratic regime before the advent of the Nazi inferno. In January, 1922, Rathenau was nominated Foreign Minister – the highest position any Jew had ever achieved in Germany.

His admirers described him as the charismatic and charming political genius, who saved Germany from the economic mud in which it was mired after the war. His nationalist opponents marked him as the treacherous and cosmopolitan Jew-boy, who sold out Germany’s honor to the allies for money. The anti-Semitic ambiance that pervaded 20th-century Germany meant that Rathenau’s fate was sealed. When he asked one of his friends why his achievements failed to prevent profound hatred of him, his friend answered, “You are a walking contradiction to the anti-Semitic theory that Judaism harms Germany. That is why they wish to kill you.”

On June 24, 1922, Rathenau was riding his convertible on a street in Berlin when three hit men from extreme right-wing factions assassinated him. The murder rocked the public. More than a million people escorted his coffin, and a general strike erupted on the day of his funeral. It took little more than a decade before the assassins’ factions entered the government, a human monster awoke from its slumber, and Walther Rathenau became a forgotten memory.