The middle of the 12th century was quite a dramatic era for the Jews of Yemen. The Fatimid Caliphate who ruled over Yemen for long time were losing territories to a religious charismatic preacher called Ali Ibn Mahdi, whose name means in Islam the Messiah, redeemer, savior. Indeed Ali referred to himself as the savior of all Muslims. He started gathering more and more followers and supporters, called for radical religious reforms and led to religious extremism. Eventually Mahdi occupied Yemen and after his death was succeeded by his son Abd Nabi Mahdi, who pretty soon became hostile and dangerous towards his Jewish subjects.

The Muslim regime in Yemen began enforcing the Jews to convert to Islam, while also issuing discriminating laws and prohibiting to study and practice Judaism. At that low point, in the year of 1172 a man who presented himself as the Messiah, whose exact name is unknown to us, started to propagate messianic messages widely, and many Jewish communities started to believe the Messiah is actually coming soon and even started to change some of their practices and prayers accordingly. Muslims too, as it it recorded, were following that Jewish Messiah, possibly believing that his arrival foretold the redemption of the Muslims and the arrival of the Mahdi.

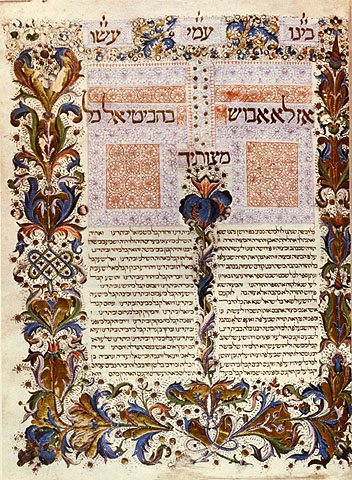

This false Messiah affair might have remained an insignificant historical footnote if it was not for Maimonides (the “Rambam”), who reacted in real time. In a famous responsa, called “Epistle to Yemen” he sent in reply to rabbi Yaacov ben rabbi Nathanel from Yemen, who wrote to him with fear about the hard times the community was going through and wondered whether that new person might be a true Messiah. He wrote to Maimonides, the most powerful Jewish authority of the time, to which the latter replied at length, with empathy and attention.

In his detailed response, Maimonides tried to console rabbi Yaacov for the bad times, asked him to pray diligently and to keep in mind that troubles come and go and will eventually pass. He urged him not to surrender to persecutions and forced conversion decrees, as these already happened in the past, yet the Jews prevailed. Maimonides referred to both Islam and Christianity as false religions not to be trusted upon, and urges the Yemenite Jews not to conduct calculations of the end of times, nor try to predict the exact time of the redemption. As for the “new Messiah”, Maimonides clearly stated that he was a false Messiah, a man not to be trusted as a true savior. He warned the Jews of Yemen and urged them to halt that man and denounce him, lest the Muslims would rage and take revenge against the Jewish community. Maimonides ordered rabbi Yaacov to copy and spread his response to all communities, as he honestly feared for them and reckoned the Jews of Yemen were in concrete and immediate danger.

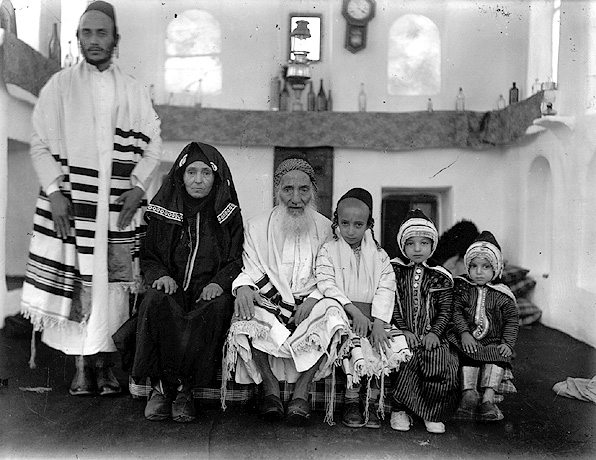

The Messianic enthusiasm in Yemen died out a few years later. Ali’s dynasty ceased to exist after but one generation. Salah a Din occupied Yemen and founded the Ayyubid dynasty, and everything was back to normal. The Rambam’s Yemen Epistle, however, remained a most significant influencing document for centuries. The Jews of Yemen could never forget what the Rambam has done for them and thought highly of him dedicating such a long wise letter for their sake. More than any other Jewish community, the Yemenites studied all his works and theories and accepted them unquestioningly. In time, two sub groups were formed among them: the Shami, who partly assimilate into the Sephardic culture and liturgy; and the Baladi, who followed Maimonides, especially the rules in his “Mishneh Torah”. It wasn’t a total division, as over the centuries, the Baladi too were “going Sephardic”, and also adopted the mysticism and messianism identified with the Sephardi tradition.

The 19th century saw a dramatic turning point, as contacts between remote communities were formed and ended the Yemenites’ isolation. Jewish scholars such as Yosef Halevi from Turkey and Eduard Glazer met with Yemenite rabbis and leaders and affected them. Rabbi Yihie Kapah, one of the most influential figures of Baladi Jews, conversed with them and was deeply affected by what they taught him about the Rambam’s rationalism and his resentment towards most mystical practices and rulings. In the spirit of the 19th century enlightenment, Halevi and Glazer claimed that mysticism was contradicting rationalism and the idea of an abstract God in Judaism.

Enthusiastic rabbi Kapah was keen to promote the new ideas and founded the “Dor Deah” movement. He preached for deserting all mystics right away, and claimed that the Zohar and other Kabalah books were to be denounced by the Yemenites if they wish to prove their loyalty to Maimonides. His ideas were provocative not only among the Yemenites but all around the Jewish world and rabbis started to react and debate. The Dor Deah dwindled after the Aliah of the Yemenites to Israel, in our days Yemenite Jews remain faithful to the Rambam and his way, just like 800 years ago, when the Messiah was allegedly coming.