Exhibitions

Search Results

Codex Sassoon: Earliest Most Complete Edition of the Hebrew Bible

Codex Sassoon is displayed permanently at ANU - Museum of the Jewish People

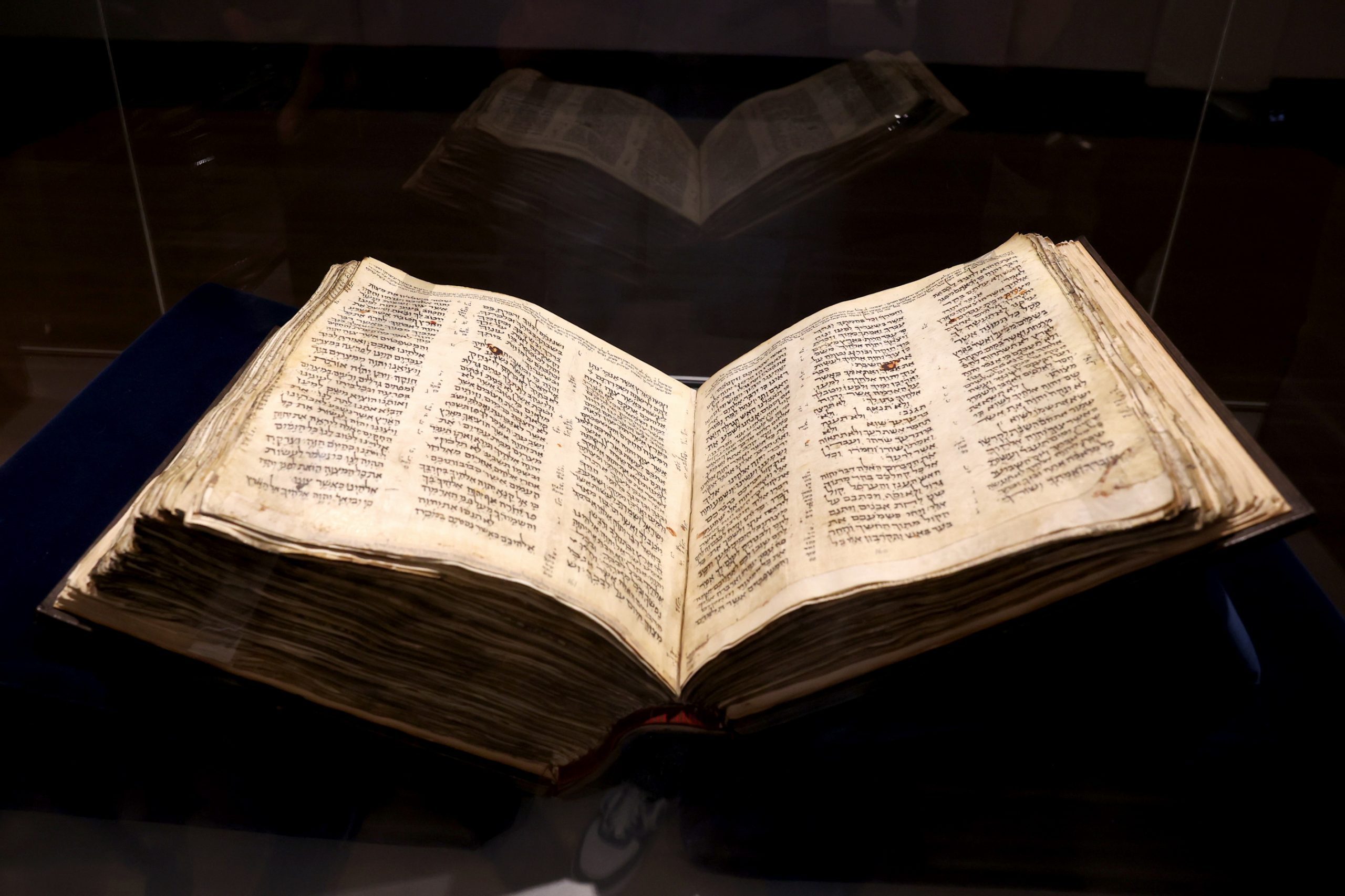

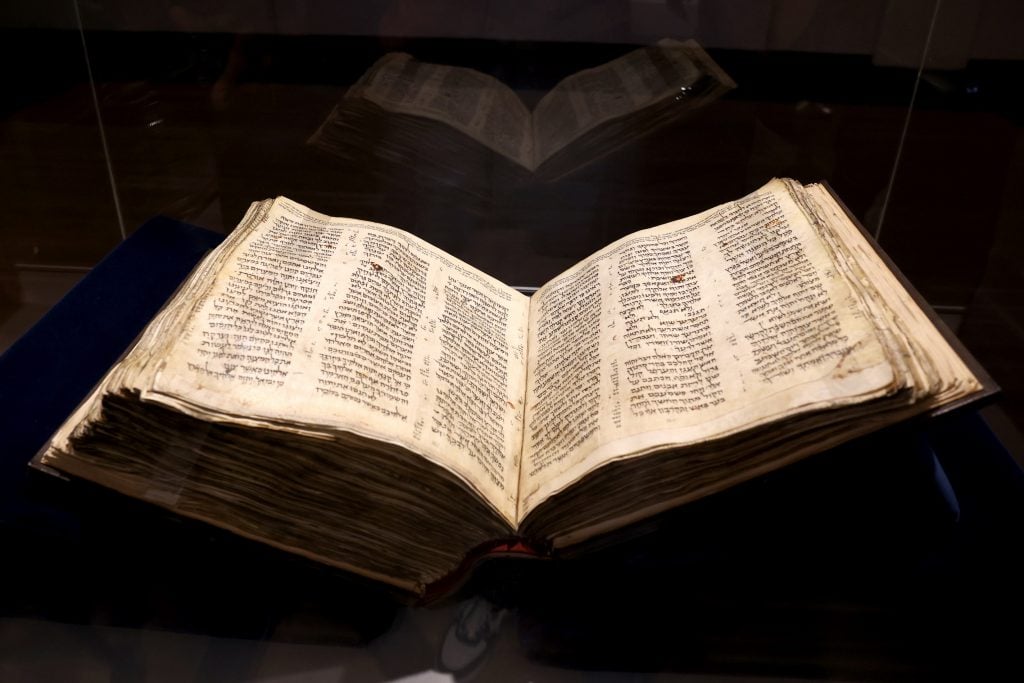

It is not every day that we get to see a book that is over 1,100 years old. Codex Sassoon, the oldest most complete Bible, is a rare and valuable testimony to the history of the biblical text. The story of the Codex itself allows a glimpse into fascinating chapters in the history of the Jewish people.

Codex Sassoon is one of the most important and unique manuscripts in the world, and in May 2023 it also became the most expensive Jewish manuscript in history: with the help of the generous donation of the Chairman of the Museum's International Board of Honor, Mr. Alfred H. Moses, the Codex was purchased for approximately 38 million dollars, at a public auction held in Sotheby's New York, and donated to the Anu - Museum of the Jewish People's collection.

We invite you to meet Codex Sassoon up close on the 1st floor of the new museum, "The Foundations" floor. During your visit you will be able to look at the original manuscript, browse through it through interactive stations and watch two films that are screened one after the other: one deals with the manuscript itself and its characteristics and the other is an animated film, based on an original composition by Yoni Rechter, dealing with the Ten Commandments.

The 24 books of Tanakh – which stands for Torah (Pentateuch), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Sacred Writings) – embody the cultural and religious heritage of the Jewish people: the story of creation, the birth story of the people of Israel, the story of the covenant between Israel and God, the laws that God commanded them, the moral teachings of the prophets, and the wisdom literature.

The Hebrew Bible has been a universal cultural and religious touchstone for thousands of years. Belief in the Hebrew Bible crosses national, geographic, and religious boundaries. The tradition of study and interpretation that is renewed in each generation allows everyone to discover new insights and personal meaning in these ancient words.

This tour will take you on a journey in the footsteps of Codex Sassoon and reveal what we know about this manuscript, the circumstances of its creation, and its history from then until today.

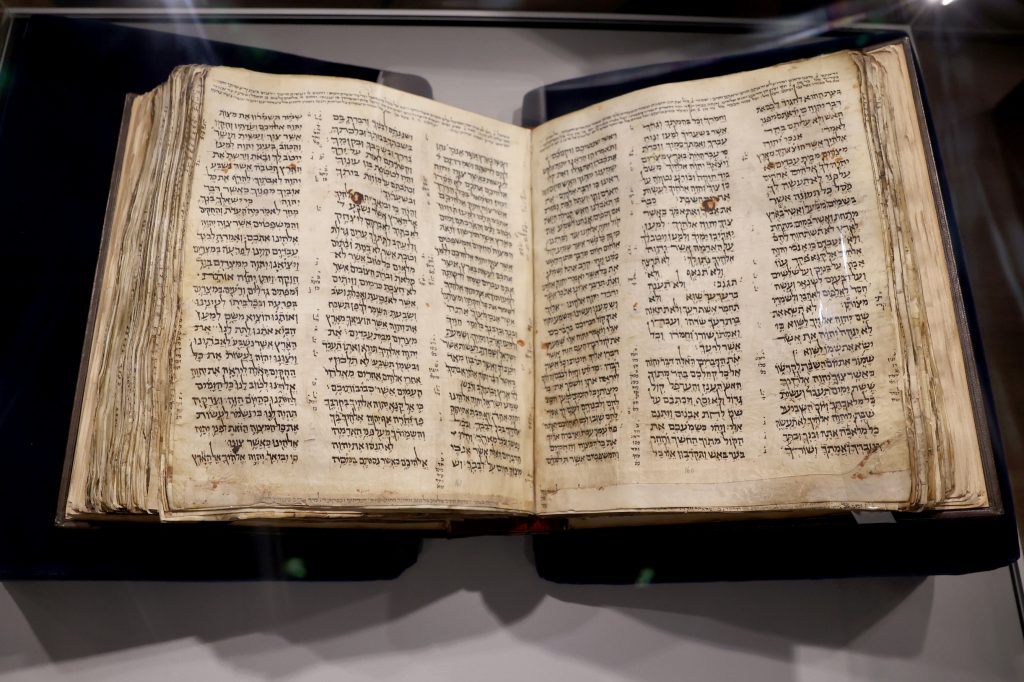

Codex Sassoon contains all 24 books of the Tanakh, written on parchment sheets by a single scribe and bound together as a book or codex. Unlike traditional Torah scrolls used in synagogues, Codex Sassoon contains vocalization, punctuation, and cantillation marks. Additionally, in the margins and between the columns of Scripture are notes about how the text should be written and pronounced according to the tradition. These are called ‘Masoretic notes’.

Over the years, Codex Sassoon underwent several alterations that left their mark. Some of its pages were lost, others were damaged, and it repeatedly underwent restoration. Today the Codex consists of 792 pages, which contain about 92% of the text of the Tanakh. It is bound in a modern leather binding and weighs about 26 pounds (12 kilograms).

Codex Sassoon has been dated to the early 10th century CE, based on the analysis of its material components and graphic features. Examination of the Masoretic notes, dedicatory inscriptions, and various repairs to the parchment until the end of the 14th century yield the conclusion that it was produced in the region of Eretz Yisrael and Syria, where it was also preserved and repaired during the first centuries of its existence.

Subsequently, for hundreds of years, there was no trace of Codex Sassoon. During the past century it was privately owned – until 2023, when it returned to Eretz Yisrael and was entrusted to the ANU Museum, to safeguard it for the public.

Over the course of more than a thousand years, Codex Sassoon drifted from community to community, locale to locale. Its fate was tied to the fates of those who produced it, shaped it, and possessed it. It tells a story of tradition and creativity; of migration and displacement; and of disappearance and rediscovery – like the story of the Jewish people itself.

The Masoretic Project and Codex Sassoon

In antiquity, books of Scripture were written without any marks to indicate how to pronounce each word, where each verse ends, and how to chant the words. This is how the Torah scrolls used in synagogues are written to this day. The tradition of how to read the Torah was transmitted orally, from generation to generation, until the 7th–8th centuries, when groups of scribe-scholars in Babylonia and Tiberias began to commit these traditions to writing using vocalization and cantillation marks. They also began composing notes with the goal of preserving the tradition of how to write and read Scripture, thus safeguarding the fixed, accepted text from copyist errors. These notes are called ‘Masoretic notes’, and the scribe-scholars who wrote them are called ‘Masoretes’ or ‘Ba’alei Ha-Masorah’.

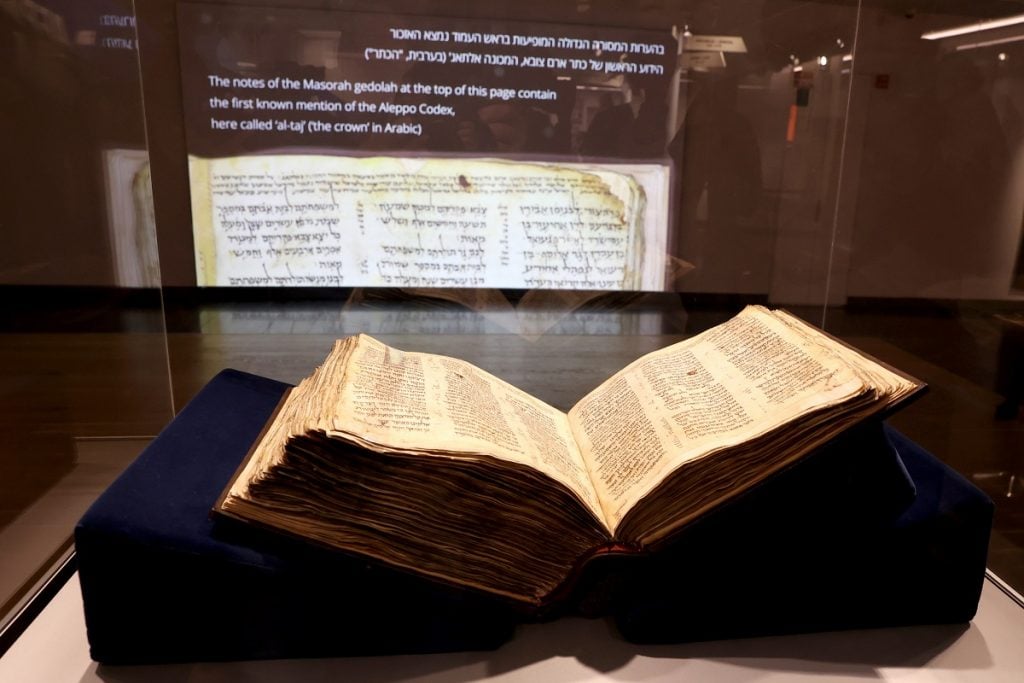

The Masoretic notes can be divided into the ‘Masorah parva’ or ‘Masorah ketanah’, which are succinct and written alongside the Tanakh text, and the ‘Masorah magna’ or ‘Masorah gedolah’, which elaborate the terse notations of the Masorah ketanah and are written in the upper and lower margins of the page.

The Masoretic notes in Codex Sassoon were written by two different Masoretes from different times. Their notes are distinguishable by the color of ink, handwriting, and the nature of their contents. In many places, the later Masorete erased the notes of the earlier Masorete and replaced them with his own notes. Sometimes he deleted the notes of the earlier Masorete but did not add his own notes.

In his notes, the second Masorete mentions important Masoretes who were active in Tiberias alongside Babylonian traditions. But the most important source that he mentions, and on which he relies, is the Aleppo Codex – which he calls ‘al-taj’(‘the crown’) – which contains the notes of the greatest of the Masoretes, Aharon ben Moshe ben Asher. These notes constitute the earliest attestation to the existence of the Aleppo Codex, to its being called ‘al-taj’, and to its attribution to Aharon ben Asher.

The second Masorete even corrected the Scriptural text to make it conform to Masoretic notes that he added on the page, thus bolstering the codex’s importance as a reliable witness to the Scriptural text.

Sacred unto God - not for Sale: Codex Sassoon during the Middle Ages

Over the years, Codex Sassoon accrued inscriptions documenting some of its history and identifying some of its owners. One Judeo-Arabic inscription, dated to approximately the year 1000 CE, attests to the sale of the codex by Khalaf ben Avraham to Yitzhak ben Yehezkel al-Attar in the presence of two witnesses. The scribe who documents the sale does not mention the location or date of the transaction. He blesses the buyer, Yitzhak, that God should enlighten him with the Torah and that his descendants should study it. And indeed, at the top of that very page is another inscription – this one in Hebrew – in which Yitzhak entrusts the codex to his sons, Yehezkel and Maimon. He declares that the book is “sacred unto God” – a sacred trust, not private property – prohibits its sale, and curses whoever dares sell or steal the book.

Another series of inscriptions recount the history of the codex during a later period. One inscription, divided across two pages, likewise declares the book sacred to God and designates it as property of the synagogue in Makisin. The inscription forbids sale of the codex and threatens anyone who does so with a curse. We know very little about the Jewish community of Makisin. It is identified with the modern-day Markada, in northeast Syria, and it is mentioned in the writings of Obadiah the Proselyte, an Italian traveler from the first half of the 12th century who passed through Makisin on his journey from Aleppo to Baghdad. The last page of the codex bears sole witness to the tragic fate of the community and the destruction of its synagogue. The codex, the inscription states, was entrusted to Salama ibn Abi al-Fakhr on condition that he return it to the synagogue after it is rebuilt. If it is not rebuilt in his lifetime, his sons would inherit the codex under the same terms. This inscription is dated to the late-14th century at the earliest. Its ownership and whereabouts from then until the early 20th century remain unknown.

Rediscovery in the 20th Century

David Solomon Sassoon was an heir to a Baghdadi family of merchants and bankers that spanned the globe. He was born in Bombay (Mumbai), India. His father, Solomon Sassoon, ran the family’s international trading firm. His mother, Farha (Flora) Sassoon, was a trailblazing woman, a Torah scholar, and a skilled businesswoman. When David was still young, his father died, and his mother took charge of his education by hiring private tutors. It was then that he discovered his love of books. As an adult, David devoted himself to collecting and studying ancient Jewish manuscripts from around the world. He held the most valuable private collection of Hebrew manuscripts, which he made available to scholars and even studied himself.

In 1929, David Sassoon received an offer to purchase a Tanakh manuscript that, it was claimed, is among the oldest known. That manuscript sits before you now; it would ultimately be called by Sassoon’s name, but at the time it was still in private hands in Ankara, Turkey. Sassoon inspected the manuscript and, after some bargaining, bought it for £350. He had it rebound and assigned it the shelf mark 1053, which is still stamped on its spine. After further examination, Sassoon averred that the codex was written in the 10th century CE.

During the 1970s, Sassoon’s descendants sold off part of his collection. In 1978, the British Rail Pension Fund bought Codex Sassoon as part of its strategy of investment in artistic and cultural assets. The codex was deposited with the British Library in London, where it was displayed publicly only once, in late 1982, at an exhibition devoted to Hebrew manuscripts from the Sassoon Collection.

In 1989, the codex was once again put up for sale, and it achieved the highest price ever for a Hebrew manuscript – the second highest price for any manuscript at the time. It became part of the collection of Jacob (Jacqui) Safra of Geneva, Switzerland, a businessman and investor from a banking family that originated in Aleppo, Syria.

In 2023, the codex was acquired by Ambassador Alfred H. Moses for 38.1 million dollars, and gifted to the collection of ANU – Museum of the Jewish People, to safeguard it for the entire Jewish people.